Alasdair Gray’s A Life in Pictures (2010) collects nearly 300 examples of Gray's prolific output as a painter and illustrator dating from the early 1950s to the late 2000s. Although expansive, the illustrated autobiography provides more than a broad brushstroke of the artist's life's work.

A Life in Pictures (2010) book jacket, courtesy AGA

As a student at the Glasgow School of Art in the early fifties, we learn that Gray rejected the conservatism of tutors who painted the way ‘Monet might have painted had he been timid and Scottish, with an inferior grasp of colour and design’ (LIP, p45). Gray’s sinewy line drawings of naked figures inspired by Blake, Breughel and Bosch, cast aside the delicate shading encouraged by his tutors. Their firm outlines and display of subcutaneous muscle and bone – a style rooted in a morbid fascination with ‘the nerves, veins, glands… [and] muscular and connective tissues that amount to a human being’ – prompted one tutor to ask if he ‘needed to make people look ugly and tortured?’ (LIP, p38, italics Gray’s).

Reclining Nude (1955), Nude on Chair (1954), Nude at Red Table (1954), courtesy AGA

Gray’s later portraiture tells a different story. In a chapter of A Life in Pictures titled Bared Bodies, which is dedicated to the vast number of nude female figures Gray painted and drew between 1964-2010, the artist shows a more delicate hand. The 1977 oil painting of Kate Copstick below (unfinished until 2010), Gray considers his most accomplished portrait. Describing his painting process he writes, ‘Kate sat very patiently through more sittings than I recall while I carefully painted as well as I could, like Cézanne making each brushstroke correspond to a glance at a small area of skin: a colour that differs, however slightly, is mixed before the next stroke is applied’ (LIP, p147).

Kate Copstick (1977-2000), courtesy AGA

Gray's oil painting shows his shift in interest from the anatomical grotesque of his early nudes (a fascination partly precipitated by his own ill health as well as his mother’s death in 1952, the year he enrolled in Glasgow School of Art). In Gray's portrait of Kate Copstick, his principal interest appears not to be death or human suffering, but rather in capturing, with diligent care, the bright, glowing skin of youth.

The characteristic firm outlines that disappointed Gray's tutor, did not, however, fade with his new found interest. ‘To paint steadily like Cézanne requires an unearned income’, he states. His more economic method of ‘swiftly putting a line round’ his subject and making the background ‘look like skin with surrounding colours and tones’, proved more viable for the financially deprived artist. The pencil drawing of Beth McCulloch that you see below was drawn onto red paper upcycled from a Glasgow photography studio (LIP, p144). The illustrious oil painting of Kate hides its own humble beginnings. Its surface was once a panel of a prefabricated kitchen counter. Gray found it discarded on a pavement (LIP, p147).

Red Beth (1968), courtesy AGA

Gray’s matured style perhaps also indicates his perception of the naked figure not as a mere collection of ‘nerves, veins [and] glands’. In his creative process and in the results seen in his completed work, Gray appears to have developed an understanding that ‘muscular and connective tissues’ do not, in fact, amount to a human being. Gray's female nudes appear more esteemed, more complex, more alive than bits of flesh on display. It is partially this, I would like to suggest, that ensures Gray’s bared bodies – though often alluring and sensual – largely refuse the objectifying eye of the spectator. There is a certain comfort in their poses, a directness to their stare or a sense of self-containment in their looking away as evidenced by Danielle below.

Danielle: Black, Red, Silver, Wan (1972), courtesy AGA

The women of Gray’s portraits appear naked, not nude. It is a differentiation John Berger makes in his celebrated book and television series Ways of Seeing (1972):

'What does a nude signify? It is not sufficient to answer these questions merely in terms of the art-form, for it is quite clear that the nude also relates to lived sexuality. To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude. (The sight of it as an object stimulates the use of it as an object.) Nakedness reveals itself. Nudity is placed on display' (Berger, 1972).

As Grace Richardson will later argue in her essay, Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster, the sexualisation of Bella’s female body by her male counterparts is a form of gendered persecution that amounts to objectification. But what’s to stop a spectator from turning Gray’s bared bodies into objectified nudes? Gray’s females have, after all, been placed on display in publications, catalogues, in galleries, on the walls of the artist’s home. The blunt answer is nothing. But as discussed, the models' representation as fleshly, autonomous human beings with their own idiosyncratic attitudes, through which they might be ‘recognized for oneself’, at least dissuades an objectifying eye.

Another key aspect of what makes Gray’s bared bodies naked not nude, is achieved through his acknowledgement of the women with whom he worked as collaborators with their own creative autonomy. ‘I always ask my sitters choose poses they like’, Gray writes. ‘Danielle mostly liked the poses in which she lay upside down’ (LIP, p147). Of Beth McCulloch he writes, ‘[Beth] was a housewife and mother without time to develop her own artistic ability, so was glad to help me make pictures she could not paint herself…[her] faith in my art greatly helped me’ (p144). Here we see a reciprocal relationship between artist and sitter based on mutual respect, trust, shared enjoyment and encouragement. Part of what makes this relationship possible is Gray’s own un-objectifying eye: drawing the body of a naked woman filled him with ‘admiring wonder’. It was ‘tantalising’, he states, ‘but aroused no emotions that stopped the work of drawing what I saw’ (p143).

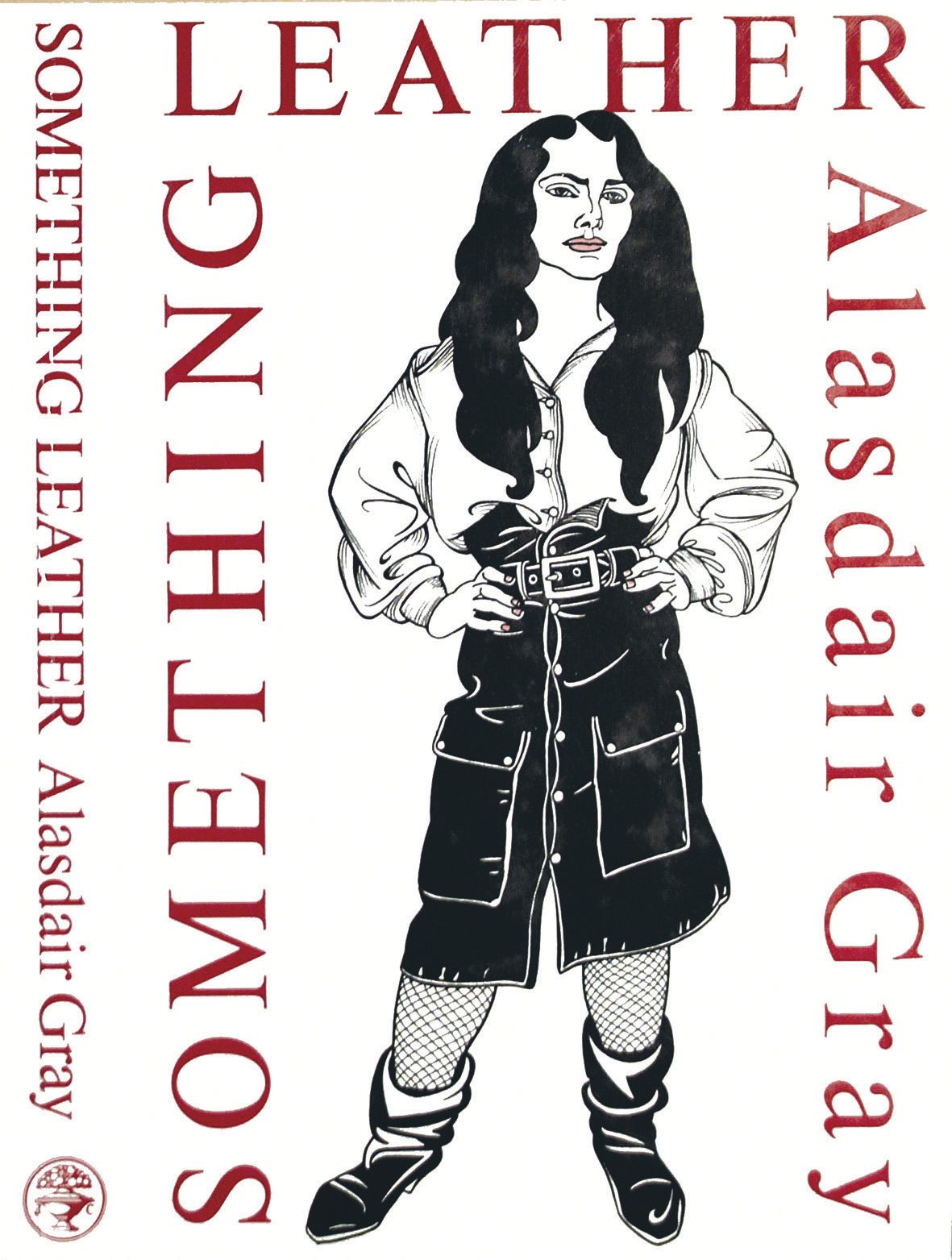

But why should you believe Gray? He is after all the writer behind Something Leather (1990), a less celebrated litterary work that draws on pornography and emphasises the sexually arousing aspect of women’s clothing. And more to the point for our story of conflicting narratives in Poor Things: A Novel Guide, in A Life in Pictures, Gray is the sole the narrator of his own life story. Why would we believe his truth to be the real truth? Well, because unlike Archibald McCandless’ story, Gray’s narrative is corroborated by one of his most frequent sitters, his close friend May Hooper.

May on Very Striped Coverlet (1984-2010); May on Striped Coverlet (1984-2010), courtesy AGA

May on Invisible Armchair (1984-2010), courtesy AGA

Hooper's account of Gray’s creative process substantiates his own. But why believe me when you can listen to her speak her own truth? To hear May's story click the Unlikely, Stories Mostly icon below. You'll be taken to The Chair, the first episode in the podcast series Unlikely Objects Mostly whose title was inspired by Gray's short story collection Unlikely Stories Mostly (1983).

Or to follow May Hooper back to Bella you’ll need to find Something Leather. The choice is yours.

Written by Rachel Loughran