Bella Baxter

Draft sketch of Lanark cover image (1982), courtesy AGA

Character Description: Bella Baxter

The extremely beautiful and disturbingly bizarre Bella Baxter is an enigma, whose peculiar life story unfolds in Archibald McCandless’ autobiography. Fished out of the Clyde after committing suicide, she is brought back to life by Godwin Baxter’s "scientific" intervention to replace her dead brain with that of her 9-month-old foetus. At the beginning of her new life, she is practically a baby inside a ‘tall, beautiful, full-bodied figure [which] seemed between twenty and thirty years” (p29). Indeed, she is a ‘gorgeous monster’ (p91) whose ‘birth’ is no less grotesque than that of Frankenstein’s creature. After her physical ‘reconstruction’, she is then ‘re-created’ by McCandless, who meets her through Baxter and dedicates his autobiography to tracing her life. It is through his autobiography that we learn she (in her life as Victoria Blessington nee Hattersley) has been married to an English general called General Sir Aubrey de la Pole Blessington, who believes that she suffers from erotomania. It is also McCandless’ autobiography which informs the reader of Bella’s many escapades with different men in various geographies.

Any information on Bella comes from the men in the text. The only time we hear directly from her is a letter she sends home; even then, her words are mediated by Baxter as he reads them out loud and ‘translates’ them into ‘proper English.’ The actual letter is shown only to reveal that Bella’s speech pattern and calligraphy have regressed into “an earlier phase” (p151) of mental development. While Godwin is seemingly amazed by Bella’s “spiritual insights [and] analytical acuteness” (p151), his amazement is rooted in his own capabilities as “God” (p143). In this regard, Bella remains an extension of his narcissistic self-regard rather than a woman in her own right. Each man in her life objectifies and sexualises her. She is idealised by Godwin Baxter and Archibald McCandless as the embodiment of female perfection, calling her the “acme of womanly perfection” (p53). For Duncan Wedderburn, the man with whom she elopes, and General Blessington, however, she is the temptress par excellence – a grave danger to men and should be eliminated: she is ‘the White Daemon who destroys the honour and manhood of the noblest and most virile men in every age’ (p94).

Her physical appearance is sketched in the novel in the form of a painting (with several references to Scotland such as the plaid, thistle, and the Edinburgh Observatory) attributed to William Strang, the famous Scottish artist (p45). Named Bella Caledonia, she metaphorically stands for Scotland – similarly ruptured, reconstructed, and recreated, whose destiny is thus shaped forcefully by others.

Bella Baxter is constructed in every sense of the word, physically and discursively. Her identity remains a mystery; testimonials about her life are extreme, verging on fantastical. The mystery lies at the core of Poor Things, deliberately unsettled by the novel’s contesting narrative voices.

Written by Papatya Alkan Genca

Poor Things (1992) is a novel ‘overflowing with political debate, ethical negotiations and discussions of social issues’, writes contributor Grace Richardson in her essay Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster. As Richardson argues, it is the novel’s discourse about gender politics where these three themes meet, bringing sharper focus to ‘the poor thing most affected’ by their merging, Gray’s resilient heroine, Bella Baxter.

In many ways, Bella’s story is one of inspiring transformation. Her reconstruction from two poor things – the first, the dead body of a young woman, abused by her father and then by her husband and the second, her unborn child – offers her the salvation provided by social improvement. The novel implies that Godwin Baxter's liberal education of Bella contributes to these improved circumstances, as does his acceptance of her need for an independently perused curriculum based on experimentation, cultural immersion, and the accumulation of knowledge through experience. Bella’s transformation is, however, also a reversal. The brain implanted into Bella’s skull is the child of Victoria and General Blessington. As Bella, Victoria’s mind reverts to infanthood (though happily not her own). The rebirth of her husband’s progeny diverts the trajectory of his lineage. Thus, it is a reversal that stamps out the idealogies and inherited social systems the General would have passed onto his child: colonialism, elitism, a place in the rigid British class system, cruelty. There is another positive to be taken from Bella's rebirth. We might recognise a little of ourselves in her transformation: if we could only live our lives over, unburdened by the experiences of the past, we too would see the world with fresh eyes. Above Baxter’s pedagogy, it is Bella’s ability to see the world with unburdened eyes, that is her most transformative quality. It is this ability that allows her to resist oppressive gender expectations with radical inhibition, and develop a social conscience that sees human suffering as terrible, painful, but not inevitable. In her eyes, human suffering is a trigger for social reform.

In chapter 20, having returned to her home at 18 Park Circus, Glasgow, Bella recognises that she is untainted with the cynicism that often couples experience (p197). There remains, however, a key truth missing in Bella’s knowledge of the world. She never discovers Baxter’s secret locked inside her, that her brain is that of her unborn child. I would like to suggest that it is this factor - her immovable, but misplaced faith in the integrity of her guardians – that keeps her from cynicism. It is also this factor, that makes her story one of everyday tragedy. Is it not the loss of faith in a parent, also the loss of faith in the world? That it is a lie keeping Bella from disillusionment, is surely a message of the most striking cynicism.

In a draft manuscript of Gray's unpublished screenplay, Poor Things, which is held at the National Library of Scotland, we see Bella wrestle with the scraps of knowledge she has either learned or senses about her unrealised motherhood. As the script directions state, Bella, in bed, naked and alone, stares down the barrell of the camera. She says:

I had a baby once. God is that true? If it is true what has become of her? For I am somehow sure she is a girl. This is a thought too big for Bell to think. I must gown into it by slow degrees.

To whom is Bella speaking? Herself? A trace of Victoria she somehow remembers? Godwin? God? Any such way, Bella is also speaking to us. It is this young woman's honest address to an audience - someone, anyone out there - that pulls us in towards her by degrees. Her nakedness only intensifies her condition as a newly born child herself. Bella's naivety also her strength. Her blindness to her guardian's unwelcome truth, is her passage to security in this world.

‘Poor Things film’ in folder ‘A’ dated 21st June to early July 1994, Acc 12557/5, courtesy National Library of Scotland

But perhaps Bella is not really of this world - of our world. The Bella of our world – or certainly the world of Victoria McCandless – is punished for her radical social reform. In the end notes of Poor Things we learn that Victoria McCandless MD is publicly ridiculed by hostile press coverage for her involvement in radical socialist and suffragist movements. Her contribution to womens' medical care is touted as lunacy (pp 302 -317). We might then recognise Bella for what she is: a figment of McCandless’ imagination. Bella is the product of a man’s dream, not for a better wife, but for a better world for the ‘woman who made [his] life worth living’.

Poor Things (1992), courtesy AGA

This introduction to Bella Baxter is, of course, only one interpretation of Gray's principal poor thing. It thus seems like the perfect time to hand you over to another voice who has - so far - avoided the bitter cynicism your editor has evidently gained. Scroll below for Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster.

by Grace Richardson

Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster Part One

Poor Things is overflowing with political debate, ethical negotiations, and discussions of social issues, all of which are overarched by the novel’s focus on gender politics. One of the poor things who is most often affected by these concerns is Bella Baxter. The novel, a satire on the politics and social dynamics of the Victorian era, foregrounds male desire that is in contention with the social and sexual liberation of woman in the 19th century. It is a conflict embodied in ‘the woman question’, a debate which scrutinized the changing political and economic status of Victorian women and responded their increasing demand social and sexual autonomy. The novel’s multiple narratives mean that there is no singular truth presented, instead it is more important the reader understands the world of Poor Things as being filled with discourses and ideas that all claim to be right. Once we understand this, the reader is offered a fascinating insight into the ways in which patriarchal power seeks to undermine female autonomy, as well as the ways in which one woman (Bella Baxter) works against this. What will become increasingly clear is that despite the various male characters’ attempts to control and confine Bella, she censors neither her behaviour nor actions.

One way to explore the gender politics that shape Bella’s experience is to focus on two key concepts of the novel –‘making’ and ‘scarring’ – which present themselves in different ways throughout the heroine’s narrative. Both concepts help us understand how Bella imprints herself on others and is, herself, imprinted on by those she encounters.

Poor Things (1992), courtesy AGA

Poor Things is a novel about making, more specifically, the making of a woman. In McCandless’ Episodes we are introduced to the novel’s key protagonists through chapters entitled ‘Making Me’, ‘Making Godwin Baxter’ and ‘Making Bella Baxter’. And since we are taking a gendered look at the novel, a question arises: what does “Making Bella Baxter” look like in relation to the society of 19th century Britain?

‘It seems that women who have not been wed by wedders like my Wedder all possess a slip of skin across the loving groove where Wedderburns poke their peninsula. The slip of a skin he never found on me. “And how do you explain the scar?” he asked, referring to a thin white line which starts among the curls above my loving groove and, like the Greenwich line of longitude, divides in two the belly of Solomon has somewhere likened to a heap of wheat. “Surely all women’s stomachs have that line.” “No, no!” says Wedder. “Only pregnant ones who’ve been cut open to let babies out”. “That must’ve been B.C.B.K”, I said, “the time Before they Cracked poor Bella’s Knob”. I let him feel that crack which rings my skull just underneath the hair’ (p107).

Through reading the quote above, it becomes evident that ‘Making Bella Baxter’ is inextricably linked with constructing her female body. McCandless’ narrative presents Bella Baxter as a surgical creation of Godwin Baxter. As McCandless’ story goes, after pulling an unknown female body from the River Clyde, Baxter revives the woman from her death by suicide and implants the brain of her unborn foetus into her skull. In a gender-inversion of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bella, the 25-year-old woman, is rebirthed through Baxter’s experiment. It becomes clear that ‘Making Bella Baxter’ into a proper Victorian woman was an impossibility as her bodily make up defies these norms. Bella is considered abnormal because despite her mental age, she is not a virgin, and her hymen is broken. She also makes childlike references in her letters to her hymen as ‘a slip of skin’ and her vulva as a ‘loving groove’, showing that although she has never been given the right vocabulary to describe her body, it has been unfairly treated and harmed at the hands of men.

Bella’s head and stomach are literally scarred by her ‘re-birth’. Bella’s scarring is not just literal, however. If we take the word ‘scar’ to mean ‘a lasting impression’ as well as a ‘wound’ or ‘mark’, then we can begin to take a closer look at how Bella imprints her mark, that is to say, her influence, on others.

Poor Things (1992), courtesy AGA

One way of achieving this is by examining Bella’s sexuality. Bella’s sexual autonomy leads the men of the novel to harbor emotive reactions toward her. If we are to believe McCandless’ version of events, her sexual needs and obsession with ‘wedding’ (sexual intercourse) in her past-life as Lady Victoria Blessington lead her husband General Aubrey Blessington De La Pole to have her institutionalised. In an inversion of this plot point, the man she elopes with, Duncan Wedderburn, is committed to a Glasgow mental asylum after realising Bella views him chiefly as a sexual object. Although this is exactly how he has treated Bella and prior conquests in the past, Wedderburn is shocked that a woman has the capacity to dehumanize men in the pursuit of sexual pleasure: ‘I had never before heard of a man-loving middle class woman in her twenties who did NOT want marriage, especially to the man she eloped with’ (p81). The unorthodox sexual outlook of Bella (previously Victoria Blessington nee Hattersley) equally unsettles Blessington. For the General, the abuse of socially non-resistant women like his mistress, Dolly Perkins (whom he abandons pregnant), is a social norm. In contrast to Dolly, Bella is an example of the 'New Woman' (Buzwell, 2014). The 19th century term for an economically independent and spirited woman who exercises control over her life was popularised by Henry James (among others) in novels Daisy Miller (1978) and Portrait of a Lady (1881).

The portrait Gray paints of his leading lady in Poor Things is conflicting. Bella’s scar, for example, creates multiple different explanations. McCandless states that it is a result of the incision Godwin made while switching Bella’s brain, whilst Victoria states in her letter to posterity that it is the result of a beating by her father which left her unconscious at the age of five. Wedderburn labels it a “witch mark” or “the female equivalent of the mark of Cain, branding its owner as a lemur, vampire, succubus and thing unclean” (2002, p.89). For Wedderburn, Bella’s scar makes her a monster, marking her as a threat and something to be feared. It was not uncommon for witch hunts to take place in Scotland throughout the 16th and 17th century. Under the supervision of James VI’s royal commissions, at least 400 people were put on trial for witchcraft and diabolism during a 6 month campaign later known as The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597. Of all the individuals accused of witchcraft in Scotland's history, 85% were women (Toil and Trouble: Witchcraft in Scotland, The University of Aberdeen). To accuse Bella of having a ‘witch mark’ Wedderburn is stating his belief that Bella is a threat to the order of the state and needs to persecuted. After all, as evidenced by The University of Aberdeen data, a witch hunt is essentially a women hunt; a means for the powerful to persecute the powerless.

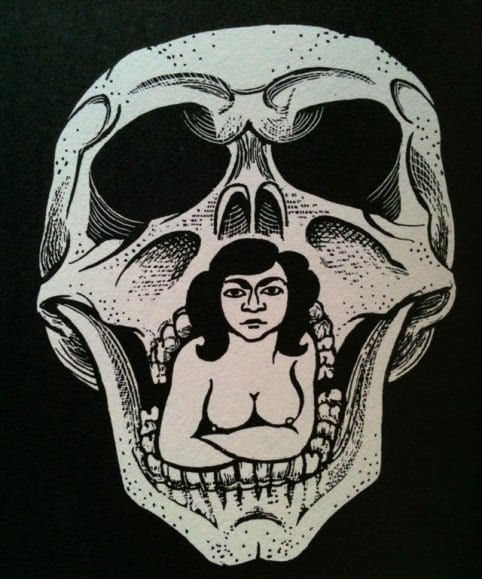

Corruption is the Roman Whore (1965), courtesy AGA

Another form of gendered persecution evident in Poor Things can be explored through the male characters’ various attempts to assert their dominance over Bella. Near the beginning of the novel when Baxter and McCandless quarrel over the matter. McCandless states: ‘You think you are about to possess what men have hopelessly yearned for throughout the ages: the soul of an innocent, trusting, dependent child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman’ (p36). The sexualisation of Bella’s female body constitutes another form of persecution. McCandless admits that throughout time men have sought women for their bodies, even admitting that men would prefer a less developed child’s brain, rather than a fully developed adult’s brain. Although not admitted explicitly by either McCandless or Baxter, we can assume this preference is owing to the man’s greater ability to manipulate such women into fulfilling their sexual needs without question. This implication somewhat sullies Gray-the-Editor’s account of Baxter (explored in the ‘Godwin Baxter’ section of this guide) as an ‘astonishingly good, stout, intelligent, eccentric man’.

Despite the male characters’ attempts to control and censor Bella, her resistance to gendered persecution is shown in her refusal to conform to their demands . This often results in accusations of madness and female ‘monstrosity’, where Bella is defined as a ‘monster’ or ‘aberration’ (p89) for her refusal to abide by societal rules. To be a monstrous woman does not always mean that the woman is literally a monster or a creature. Nor does it necessarily correlate with physical unattractiveness. Bella’s appearance is presented in a wholly positive light. To McCandless, she is a ‘glorious dream’ who ‘shone before’ him ‘solid, tall, elegant’, like ‘a rainbows end’ (p44). Though a ‘monster’ to Wedderburn, she is still ‘gorgeous’ in his eyes (p91). Bella’s monstrosity denotes her transgressive, deviant nature as it appears to men through her behaviour. To be considered monstrous, the female must refuse or be unable to conform to the prescribed social conventions of her given time and culture. Her behaviour will thus be perceived as monstrous or unnatural (a condition Kirsten Stirling explores in Bella Caledonia: Scotland Deformed). By rejecting what is considered ‘normal’ and ‘natural’, the female monster questions the ideological and patriarchal constructions of what the female body and feminine behaviour should look like, whilst also revealing the underlying anxieties of a given society or historical period. There are a number of women besides Bella who defy societal norms for women of the period or who are abused owing to their gender. Contributors Sara Sheridan and Lucy Lauder explore these issues further below.

Character Description: Poor (female) Things

There are a number of peripheral female characters in Gray’s novel including Godwin’s mother and housekeeper Mrs. Dinwiddie, Madame Cronquebil and her Parisian sex workers and General Blessington’s rejected mistress, Dolly Perkins. As with all the characters that circulate round Bella Baxter, these women are foils that bring to light aspects of her character. All are working class and therefore socially vulnerable, indeed their stories are defined by the behaviour of men towards them – a comment in itself on female autonomy in the 19th century. ‘I learned at Millie Cronquebil’s how weak and lonely women are used’, Bella knowingly states on her return to Glasgow (p195). Mrs Dinwiddie (a servant) was Godwin’s father’s mistress and is kept in her position even when she becomes pregnant by him. Madame Cronquebil and her Parisian sex workers are at the mercy of a male justice system. Madame Cronquebil has to bribe an official when Bella is too forthright with a customer (using the money that Bella has earned during her time in the brothel). Dolly Perkins, who we never meet in person, was a maid in the Blessington household and was set up by the general as his mistress. When she becomes pregnant (possibly not by him) she is thrown onto the streets. In all cases, Bella is open-minded and generous to these women. In the case of Dolly Perkins she displays these character traits as Victoria Blessington, giving money and valuable goods to Dolly even before she becomes Bella Baxter (as McCandless claims she does) Bella’s life as an upwardly-mobile, effectively upper-middle class Victorian woman is extraordinary (whichever account you believe) and is certainly informed by the frankness of the women around her. She is not protected from sexual knowledge and its social context, even if that context makes little logical sense, as the social and sexual rules for men and women are different, as they are between classes. Her acceptance of other women’s stories (as told to her by them) and her subsequent solidarity with them is a mark of her extraordinary character.

Written by Sara Sherridan

Character Description: Madame Cronquebil

In Chapter 18 of the novel, we are introduced to Madame Cronquebil. ‘Millie,’ a no-nonsense cockney, graciously puts Bella and Duncan Wedderburn up for the night in her Parisian brothel. Millie instantly takes a liking to Bella, delighted by the opportunity to have ‘a heart-to-heart talk with a sensible down-to-earth English woman’ (p172) The eccentric widow nourishes Bella generously with her tender words and astute advice. For Millie, ‘Money and Love’ (p172) are of the utmost importance: ‘French men are a lot easier to manage than British men’ (p172) and politics must always ‘be detached from the hotel trade’ (p181). Condemning Wedderburn brilliantly in the scathing image of an ‘over-sucked orange’ (p177), Millie helps Bella to free herself from his dead weight. Gaining Wedderburn’s compliance by feeding him ‘exactly the right amount of brandy, (p179) he is swiftly sent off to Calais. Millie’s spirited counsel and colourful life experiences offer an amusing contrast to Bella’s naivety, which reaches a climax in the absurd and mischievous farce of her brief stint as a sex worker. Although only with us for a short few chapters, the force of Madame Cronquebil, with her perceptive words and keen mind for business, makes her one of the most memorable characters contained in Poor Thing’s (sometimes!) bewildering pages.

Written by Lucy Lauder

Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster

Part Two

by Grace Richardson

Reflecting on both Sara and Lucy's words, leads us ask why Bella Baxter is portrayed as a monstrosity by the men in the novel? Well, she is a powerful, independent, determined woman who enjoys her sexuality and refuses to be conditioned into obeying gender and societal rules. As Kathryn Hughes explores in an essay for The British Library on attitudes towards gender in 19th century Britain, during the period women were treated as second class citizens to men in society. From the 1830s, inhabited what Victorians thought of as ‘separate spheres’. ‘The ideology of Separate Sphere rested on a definition of the ‘natural’ characteristics of women and men’. Hughes notes. ‘Women were considered physically weaker yet morally superior to men, which meant that they were best suited to the domestic sphere. Not only was it their job to counterbalance the moral taint of the public sphere in which their husbands laboured all day, they were also preparing the next generation to carry on this way of life. The fact that women had such great influence at home was used as an argument against giving them the vote. (Hughes, 2014)

Images of the domestic angel and the fallen women became prevalent in literary depictions of Victorian women. Bertha Mason, the madwoman in the attic, in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847) or Hetty in George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859) offer two such examples of the latter. Still to this day, many of us hear the word ‘Victorian’ and equate it to discussions of sexuality which are moralistic, highly repressive, and oftentimes non-existent. It was also a time, however, where sexuality became a topic of private and public attention. The ‘prostitute’ and the ‘the solitary vice’ (masturbation) were seen as a threat to national order. For women, sex was never meant to be enjoyed, it was meant purely for the purpose of procreation and women could only have sex with one man, their husband, whereas it was commonplace for men like General Blessington and Duncan Wedderburn to have ‘mistresses’. Women who had sex outwith marriage often lived a life of tragedy, such as those female protagonists in the novels of Leo Tolstoy or Thomas Hardy. Bella is the opposite of Victorian femininity: she rejects marriage, ‘weds’ outside of matrimony and enjoys her sexual encounters – all actions that were unacceptable for women of the time.

When General Blessington, the husband she left, comes to Glasgow to bring her home, he accuses his wife of having an ‘insane appetite for carnal intercourse and calls her an ‘unstable woman’, whilst declaring that ‘no normal healthy woman – no good or sane woman wants or excepts to enjoy sexual contact, except as a duty’ (2002, p.218). The education Baxter offers Bella leads her to defy Victorian norms by developing no shame or guilt surrounding her body or erotic self. As Baxter notes,

‘Her menstrual cycle was in full flood from the day she opened her eyes, so she has never been taught to feel her body is disgusting or to dread what she desires’ (p69).

Women of the Victorian period were made to feel a great deal of shame surrounding their bodies and just like every other aspect of their life, their body was under their husband’s control. Although Bella’s body was surgically and rhetorically created by men, she resists their control by allowing her desires to propel her actions, whilst she also exhibits no shame towards her body’s natural processes, in this instance, menstruation. It is therefore evident that Bella is ‘constructed by the men around her, the author included’, X’s statement on Gray’s heroine is only partially true, as Bella works against her toybox beginning to stake her own claim in the world. Bentley’s point that “Bella’s narrative …[is] the story of a strong woman’s evasion of a variety of male characters who try to impose their power over her’ (Bentley, 2008, 48) but instead encounter a woman who ‘in many cases is physically and emotionally stronger’ is a condition that seems “unnatural to the Victorian gender ideology” (Bentley, 2008, 49), is then more accurate.

The ideas of making and scarring are reoccurring motives in Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things. Bella is marked literally through her ‘rebirth’ and through patriarchal expectations of her as a woman. Ultimately, however, Bella makes herself through her own self-determination, resilience to male dominion and to willingness to resist societal norms. Just as Bella marks every person she meets, she also leaves a lasting impression on the reader. In today’s world where women’s bodies are increasingly being targeted and policed, through tabloid magazine covers, as well as government policy - need I say more than Roe vs Wade to illustrate this point – Bella can be recognised not only as a ‘New Woman’ but a modern woman, and a great example of how to fight back against the powers that be, through your own radical self-expression.

Inside the Box of Bone (1965), reworked in as colour screenprint with Glasgow Print Studio (2008), courtesy AGA

Character Prompts

Bella Baxter

How is Bella depicted from the male view point of view?

How does Bella go against society’s norms of a woman?

Find two quotes that show Bella’s personality?

How is Bella’s and Godwin’s relationship portrayed?

A question bringing the historical rooting into reality. To what extent have the attitudes towards women changed?

What does Bella’s experience say about the way society views the female body?

Is Bella a creation of men or does she create her own story?

Mospy and Flopsy

What does queer mean to you?

How does the narrative change after introducing the rabbits?

What are the rabbits a metaphor for?

Madame Cronquebil

What does Madame Cronquebil’s character suggest about female autonomy in the 19th century?

Do you think female autonomy has improved today?

Get involved! Share your response to the promts using #PoorThings

Prompts written by Grace Richardson and Janaki Mistry

What if everything you thought you knew about a person was suddenly turned on its head? Say a person like Bella Baxter, or her doppelgänger Victoria McCandless... And then what if you discovered that these two characters you thought you knew had another doppelgänger? And that doppelgänger was a real 18th century doctor... what truths might you uncover? Click on the image of Victoria McCandless and discover more by tuning in to the podcast Alasdair Gray's Medical Women: Poor Things, a Thesis and a History.