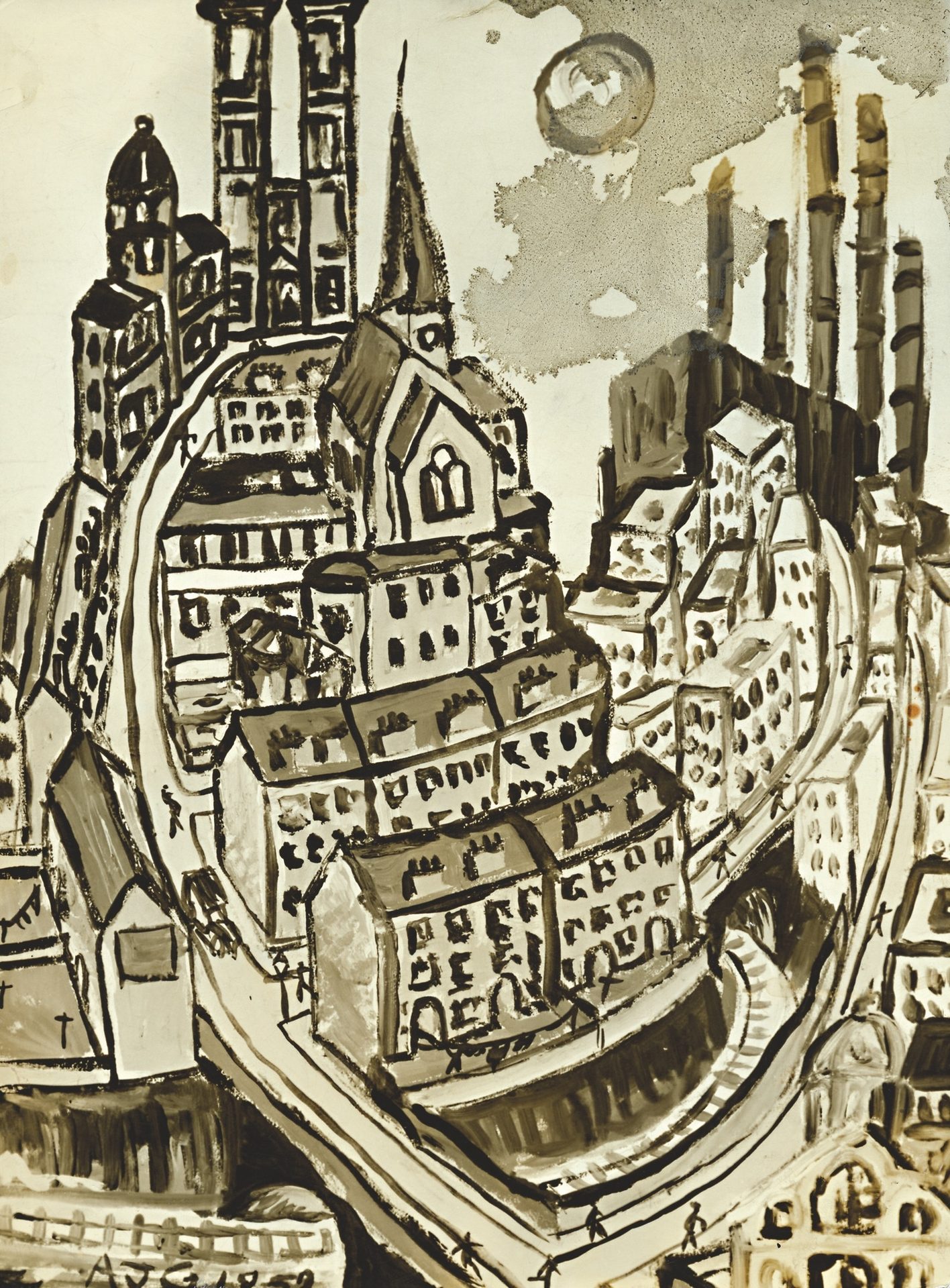

Poor Things (1992) illustration , Portrait of General Blessington, courtesy AGA

BLESSINGTON, Sir Aubrey la Pole, 13th Bart.; cr. 1623; V.C., G.CB., G.C.M.G., J.P.; M.P (L.) Manchester North since 1878; b. Simla, 1827; e.s. of General Q. Blessington, Governor of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Emilia e.d. of Bamforth de la Pole, Bart., Hogsnorton, Loamingshipe and Ballyknockmeup, Co. Cork; S. cousin 1861; m. Victoria Hattersley, Manchester locomotive mnfctr. Educ.: Rugby, Heidleberg, Sandhurst.

'At Sandhurst in 1846 a fellow student at Sandhurst fell to his death in a prank Blessington initiated…His family connections with the Duke of Wellington perhaps led to him being reprimanded instead of expelled...' (p290)

Character Description: General Blessington

General (Sir Aubrey la Pole) Blessington appears, like the ‘Thunderbolt’ he is, at McCandless and Bella’s wedding, protesting that Bella is, in fact, his wife, Victoria. His rigid attitude to life (Bella describes him as ‘a long thin stick with a mask on top”) has left him unable to sit down – he ‘can only rest when prone.’ He is the emblem of the novel’s central theme of inequality, representing both the patriarchy and the Empire. As a soldier he is violent and pitiless. According to Gray’s notes the Duke of Wellington states: Blessington ‘only feels alive when killing people.’ As a husband he is little better. Appalled at his wife’s ‘erotomania’ (her desire to sleep in the same bed with him every night) to the point of surgical intervention. ‘No normal healthy woman,’ he declares, ‘no good or sane woman wants or expects to enjoy sexual contact, except as a duty.’ When Victoria Blessington (nee Hattersley) becomes outraged in discovering that her husband is happy to express his desires on the servants, he locks her in the cellar with the intention of having her declared insane. When Bella refuses to return home with him as his wife (a part of her life she cannot recall), Blessington pulls out a revolver. Blessington’s importance to the novel is demonstrated not only in his appearance in My Longest Chapter but by Gray’s copious notes which claim the character is an existent historical figure. Blessington’s defeat provides the hopeful climax to McCandless’ narrative, though not to Gray’s…

Written by Grant Rintoul

Unlike low-born Archibald McCandless, the villain of Poor Things, General Sir Aubrey de la Pole Blessington Bart V.C., G.CB., G.C.M.G., J.P.; MP, is privately educated. As the General's numerous high-ranking titles suggest, Blessington is the face of the institution in Gray’s novel (unlike his voice which is curiously resemblant of Dickensian cockney: ‘UNHAND ME, WIFE, SIR!’ (p211). This ambiguity between title, social rank and vocal utterance can be considered the equivalent of a narrative set-piece for characterisation. Charles Dickens' Mr. Turveydrop of Bleak House (1852) offers a convincing parallel. The low-born dance school proprietor and (ironic) 'model of deportment' so convincingly adopts aristocratic mannerisms that his social circle is consequently formed of aristocrats. Blessington reverses the format: he's high-born with low born diction. Unlike the readers of Bleak House to whom Turveydrop's social background is no mystery, the anomoly between Blessington's cod Cockney accent and opposing class status goes unexplained. The comic aptness of Turveydrop's name - a reference to his tospy-turvey inversion of social class - underscores Dicken's hyperbolic parody with a rather joyous comic strain. In keeping with Dicken's Turveydrop, Gray uses naming conventions to hint at Blessington's own tosp-turvey social status. Yet, Poor Thing's author plays a more hidden hand than his Victorian counterpart.

The only trace of Blessington's less-than-aristocratic lineage is via a satirical reference to his illegitimate birth by a mother of Irish peasantry class from 'Ballyknockmeup' (p206, or see the extract beside Blessington's portrait above). That Emilia is cousin to Blessington's father, General Q. Blessington - Governor of Andaman and Nicobar Islands - casts more doubt on the family's aristocratic purity. (It also hints at the relationship between an individual's involvement with colonial advancement and their increased social status). These references are carefully tucked into a lengthy biography of the General provided by McCandless in the form of a magazine clipping. The clipping is supposedly extracted from the 1883 edition of Who’s Who (pp. 206-7).

Though a minor character in terms of his 'screentime', so to speak, the General receives a lengthy entry in Gray-the-Editor's Notes Critical and Historical. The notes work hard to convince the reader of Blessington's historical accuracy. They feature fabricated newspaper clippings and erroneous poetic tributes from Rudyard Kipling and Alfred Lord Tennyson (both variously labelled colonialists) (p290-99). But why attempt to bolster the most notably archetypal character in the novel with so many fake citations that vouch for his historical authenticity? The answer lies in the paradoxical art of truth-telling. Through Blessington, we see Gray push the boundaries of what parody can achieve: truth.

As Jonathan Coe argues in the London Review of Books (Vol. 14 No. 19 · 8 October 1992): ‘[Gray] can be a superb realist, as the central books of Lanark and the central flashback of 1982, Janine attest, but at the same time he knows that the manners, the sentiments, the clothes and the habits of speech of this ridiculous period can now only be observed through a comic filter. In this respect, the book’s most triumphant creation is ‘Thunderbolt’ Blessington, the psychotic empire-builder known to the proprietors of a Parisian brothel as ‘General Spankybot’, and commemorated in the novel’s footnotes by a splendid piece of mock-Kipling. For those who believe that ridicule is the only real ‘test of truth’ (to adopt the phrase wrongly attributed to Shaftesbury), accurate parody like this will be worth any amount of the over-careful realism practised in more solemn post-imperial novels'.

Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983) Illustration, courtesy AGA

For Coe, parody is the truth-teller par excellence. Through Blessington, we might conclude that Gray agrees. However, seemingly dissatisfied with the paradoxical clarity of Blessington's status as a truth-teller about the 'ridiculous' nature of the Victorian period, Gray pushes the boundaries of parody once more. In Chapters 22 and 23, after Bella and McCandless' ill-fated wedding, Gray fills Godwin's study with a menagerie of equally parodic figures. What ensues, is not the kind of parody that shines a light on the social mores of the period, but a cacophony of lies, half-truths, disputable evidence and subjectivity. (And more hilarious cod accents of course).

In her essay, Contrasting Truths, contributor Shona McKenzie explores some of the subjective 'truths' in Chapters 22 and 23. But first, let's discover more about the characters who appear within those pages.

Character Description: Blaydon Hattersley

A greedy man in both character and profession, Blaydon Hattersley, father to Victoria (and according to McCandless also father to Bella).

Driven by his obsession with saving money, he subjects his family to unsanitary living conditions that constitute Victoria’s impoverished beginnings. Building a wealthy lifestyle by manipulating his own brother-in-law, Hattersley is not afraid to exploit his own family members, whom he treats ‘as potential enemies who must be kept poor by violence of the threat of it’ (256). Victoria’s letter to posterity reveals that Hattersley is as cruel as he is stingy; striking her as a child, she was left with the wound that is transformed into Bella’s surgical scar in Archie’s version of events.

We first meet Hattersley in Chapter 23, ‘An Interruption’, when he and Victoria’s legal husband, General Blessington, halt Archie and Bella’s wedding to take Victoria (now Bella) back to her marital home. It soon becomes apparent that Hattersely’s motive in locating his daughter is to exploit the financial prospects of her previous marriage. The chapter reveals his function as a parasite not only to Blessington but to his daughter. For Hattersley, the relationship is transactional:

‘Think of all those grand places, Vicky, all for you and me. Me! The grand-dad of a baronet! You owe me that, Vicky, because I gave you life’ (p224)

However, upon finding his dreams of jumping upon his daughter’s marital wealth are quashed, Hattersley disappears from her life as quickly as he re-entered it.

Written by Shona McKenzie

Poor Things (1992) illustration courtesy AGA

Character Description: Detective Inspector Grimes

Seymour Grimes is a private detective hired by General Blessington to investigate the whereabouts of Bella/Victoria. He appears briefly near the end of McCandless’ tale (chapters 21-23), but his demeanor makes him a distinctive albeit minor character.

Grimes is a ‘parasite’ of Blessington’s serving as an adversary to the happiness of the book’s central trio: Archibald McCandless, Bella and Godwin Baxter. The character is written deliberately like an archetypal London copper, with his distinctive accent (perhaps the most idiosyncratic in the book) coming through his dialogue: ‘was called to investigate Lady Blessington’s disappearance seven days ago, three years after event’ (p211). He misses pronouns and conjunctions in favour of reporting the facts as quickly and plainly as possible. Grimes’ no-nonsense attitude is equally evidenced in his short bursts of his reporting, and the way his words run onto one another, prompting them to be sounded out phonetically: '…vanished fromerome sudden… (p211), “Showimphoto. ’Thatser!’ sezee. ‘Where now?’ says I. ‘Corpus unclaimed,’ sezee…” (p212), and “Can’t say – not my department,” (p212). Grimes is brought forward during the wedding’s interruption to serve as an authoritative representative of the law. This is soon contradicted when his authority is undermined by Blessington. As the General is a senior officer, the suggestion is made that Grimes, who is ex-army, is instinctually subservient to orders. Grimes only has a couple of moments to shine but serves as a suitable antithesis to the main trio, a man conforming wholeheartedly to his position in the class system, speaking only when spoken to, and performing his duties impartially and to the letter. Of all the ‘parasites’, he also shows the most respect and courtesy to his employer’s opposition.

Written by Michael Paget

Sketch of Sir Arthur Shots from McGrotty and Ludmilla (1990), courtesy AGA

This image does not portray Detective Inspector Grimes but Sir Arthur Shots

Character Description: Dr. Pricket & Mr. Harker

Alongside Detective Inspector Grimes, Dr. Prickett and solicitor, Mr. Harker comprise General Blessington's 'parasites', a Gray-the-Editor calls them i his introduction (p XIII). Both Prickett and Harker apprear in Chapters 22 and 23, where their character function is to support their employers version of events and their narrative function foregrounds the novel's concern with conflicting narratives.

Blessington’s lawyer, Mr Harker, claims that after Victoria Blessington jumped into the Clyde she was rescued by the Humane Society and resurrected by Baxter, who later abandons her to Wedderburn. The account both slanders Baxter’s character and contrasts Victoria’s letter where she states she sought Baxter’s sanctuary voluntarily. Harker also demonstrates poor legal practice by refuting Baxter’s evidence of medical paapers, calling the documents ‘quibbles’ written by ‘a horde of foreign brain doctors’ (p233).

Dr Prickett speaks from a medical standpoint, but is clearly influenced by his employer, Blessington. His account converges with Victoria's letter on a key point: they both state that the latter state that Victoria wanted a clitoridectomy, a form of female genital mutilation, owing to socially-trained bias against fulfiling her own sexual needs.

Although Prickett supports General Blessington’s version of events, he cannot be considered a straightforward villain. ‘You used to consider me a good friend, [Victoria]’, he emotively pleas (p.219). In Victoria's letter, he is also the catlyist to her salvation: Dr. Prickett refers her to Godwin Baxter, who subsequently provides her with the refuge she so desperatley needs.

Written by Shona McKenzie

Corruption is the Roman Whore (1965), courtesy AGA

Contrasting Truths

by Shona McKenzie

Contrasting truths about Victoria’s past are revealed in Chapter 22 ‘The Truth: My Longest Chapter’ and Chapter 23 ‘Blessington’s Last Stand’. Connected through parasitic financial ties, Dr Prickett, Detective Grimes, Blessington’s solicitor, Harker, and Blaydon Hattersley each reveal ‘truths’ about Victoria’s background that are underpinned by each character’s desire for financial gain and/or duty to their employer.

Dr Prickett speaks from a medical standpoint under the influence of his employer, Blessington. The doctor claims that Victoria suffered from erotomania before running away, and he was due to perform a clitoridectomy. The surgery was a form of female genital mutilation (FGM) practiced in Victorian Britain as a “cure” for women with sexual needs greater than was deemed appropriate for the period. n botickett’s account of the episode and in Victoria’s letter to posterity the characters state that Victoria wanted the surgery.

Victoria claims that Prickett referred her to a Dr. Godwin Baxter after her third hysterical pregnancy, where the two met for the first time. In both accounts, Baxter prevents the surgery, either by creating “Bella” after Victoria’s suicide, as in McCandless’ account, or in Victoria’s account by teaching her about the education system that led her husband and his console to misbrand her sexuality as unorthodox and therefore punishable.

Blessington’s private detective, Grimes, gives a linear account of events from his investigation into Victoria’s disappearance. The detective believes Victoria’s body was fished out of the Clyde, lay unclaimed for a week, and then taken home by Baxter, before being witnessed alive again. The proposed timeline of Victoria’s disappearance is conflicting. Grimes believes that ‘Lady B’ went missing on the 6th of February 1880 and was found dead on the 8th, whilst Baxter states that the pregnant Victoria did not run away until the 17th following a visit by Blessington’s pregnant mistress, Dolly. Victoria’s letter claims that whilst Blessington did impregnate Dolly, she herself was neither suicidal nor pregnant. Grimes is also unable to explain how ‘Lady B’ could have lain in the mortuary for a week before being reanimated: ‘Can’t say - not my department’ (p212). Prickett, however, believes that Glasgow doctors, including Baxter’s father, Sir Colin, have been reanimating corpses since the resuscitation of a hanged criminal in the 1820s, despite Prickett providing no evidence of this: ‘Your father was present at that demonstration’, he tells Baxter. ‘I have no doubt he passed on all he learned to you’ (p213).

Victoria’s father, Blaydon Hattersley, shows little care for the truth behind his daughter’s well-being beyond her financial potential. He even grows excited at the prospect of Blessington dying so that Victoria can inherit her husband’s wealth and provide Hattersley with an estate and a baronet for a grandson. In Archie’s narrative, Bella must either choose between the riches of her abusive marriage or confinement in a madhouse. In Victoria’s letter, Hattersley is an equally selfish and covetous man: ‘Saving money was his major passion. He seldom gave my mother enough to buy proper food’ (p255).

Blessington’s lawyer, Harker, also reveals a version of events where Bella/Victoria’s body is treated as a form of currency. He claims that Victoria jumped into the Clyde and was rescued by the Humane Society solely because they were paid to do so. He claims she was resurrected by Baxter, who bribed them to allow him to abduct and drug her, before she ‘financially destroyed’ Wedderburn (p220) at which point Baxter abandoned her. The account both slanders Baxter’s character and contrasts Victoria’s letter where she sought Baxter’s sanctuary voluntarily after their first meeting. Harker also demonstrates poor legal practice by refuting Baxter’s evidence of medical papers to prove Bella’s mental stability. He calls the documents ‘quibbles’ written by ‘a horde of foreign brain doctors’ (p233) and states that Victoria’s abuse can be discounted simply by claiming she is mad.

However, as these characters exist within Archie’s narrative, Archie holds the most authority over the manipulation of Victoria’s past. The irony of ‘My Longest Chapter’ is that, except for his outburst (which is comically ignored by everyone but Baxter) Archie has an incredibly passive role in the events that unfold. In his narrative, Bella has no authority over her past and seeks Archie to comfort her. Rather than being a hero of any kind, the Archie described in Victoria’s letter, an awkward, childish, ‘vain little homunculus’ (p268) who eradicates her past with fiction, appears to be just as much a parasite to Victoria as her father, and Blessington’s men to their marriage.

Character Prompts

General Blessington

What signs does General Blessington show of toxic masculinity?

What is revealed about General Blessington’s character when he locks Victoria Blessington in the cellar?

How does Bella’s opinion of General Blessington change?

Blaydon Hattersley

How would you describe Blaydon Hattersley’s relationship with his daughter?

How do you think Blaydon Hattersley locating his daughter to exploit the final prospects of her previous marriage would be viewed today?

Dectective Inspector Grimes

How does class affect Detective Inspector Grime as a character?

Get involved! Share your response to the promts using #PoorThings

Prompts written by Grace Richardson and Janaki Mistry