Alasdair Gray:

Social Conscience

In Kevin Cameron’s documentary film A Life in Progress (2014), we follow a camera pan across a particularly spectacular ceiling. For those of you who have been to a cèilidh, gig or general shindig under that roof, you'll know the ceiling is that of Òran Mór, Glasgow. And the mural embellished across it is that of Alasdair Gray's. In Cameron's film, as the richly emblematic figures of the ceiling mural slide into view, the artist begins to speak:

Anybody who has seen a lot of my work book illustrated works, mural-paintings – will find certain faces and figures keep coming up in them: certain emblematic or symbolic figures like the winged embryo inside the skull…many such figures I use and recycle and many mottos...

A Life in Progress, dir Kevin Cameron (2014); Òran Mór auditorium ceiling apse (2004) courtesy AGA; Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man (2004) courtesy AGA; Òran Mór auditorium ceiling apse (2004), photographed by Mark Wild

One of the mottos Gray speaks of in the above quotation is emblazoned on the rafters of Òran Mór. Look to the image above and you'll catch a glimpse of it. Gray's motto, ‘Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation’, was adapted from the title poem of Dennis Lee’s Civil Elegies (1972). Lee's poetry collection mourns the ecological destruction of the poet’s native Canada, and denounces the country's colonial complicity. It also laments the nation’s loss of independence.

Note Historical

When the Dominion of Canada was created in 1867 it was granted powers of self-government, but Britain still retained legislative supremacy. It wasn't until 1982 that Canada adopted its own constitution and became a fully independent country.

The parallel between Lee's depiction of Canada and Scotland’s status as a devolved power with aspirations of independence is evident in the poem's lines:

‘And best of all is finding a place to be/in the early days of a better civilization […] For we are a conquered nation: sea to sea we bartered/everything that counts, till we have/ nothing to lose but our forebears’ will to lose’.

Scanning Lee’s poem, it is not difficult to see why ‘work as if you lived in the early days of a better nation’, has taken on a life of its own as a slogan for the Scottish Independence movement. As long-standing supporter of Scottish home rule, it's also clear to see why the motto might appeal to Gray. For Gray, Scottish Independence is a critical route to increasing social equality (Gray, The National, 2020). Consequently, we can regard any allusion to the politics of independence or socialism within Gray's writing, visual art - and in the video linked below - as a manifestation of his social conscience.

A Life in Progress (2014) directed by Kevin Cameron

So how does Gray's motto relate to Poor Things? To find out, we should look to the words of artist once again:

[It struck me as] such a good way of approaching your own work, seeing yourself as something early and something that could be made better.

Here we see Gray advocating for existing in a state of continual, positive renewal. Remind you of anyone? Of course, it does. In Gray’s words we can almost certainly catch a glimpse of his heroine Bella Baxter. Her child’s mind is, after all, ‘something early’. It is also a mind Gray tries to prove ‘can be made better’ by its support of an equitable system that offers ‘everyone productive work in good conditions, along with good food, housing, education and health care’ (p161). That system is, of course, socialism. However, as his female protagonist demonstrates, creating a better world is also about empathy, acceptance and above all, kindness. Kindness is a trait abundant in Bella, whose empathy extends to beggars, sex workers, gamblers, animals and those like Dr. Hooker and Harry Astley whose political perspectives and lack of social consciousness come to contrast her own ideology.

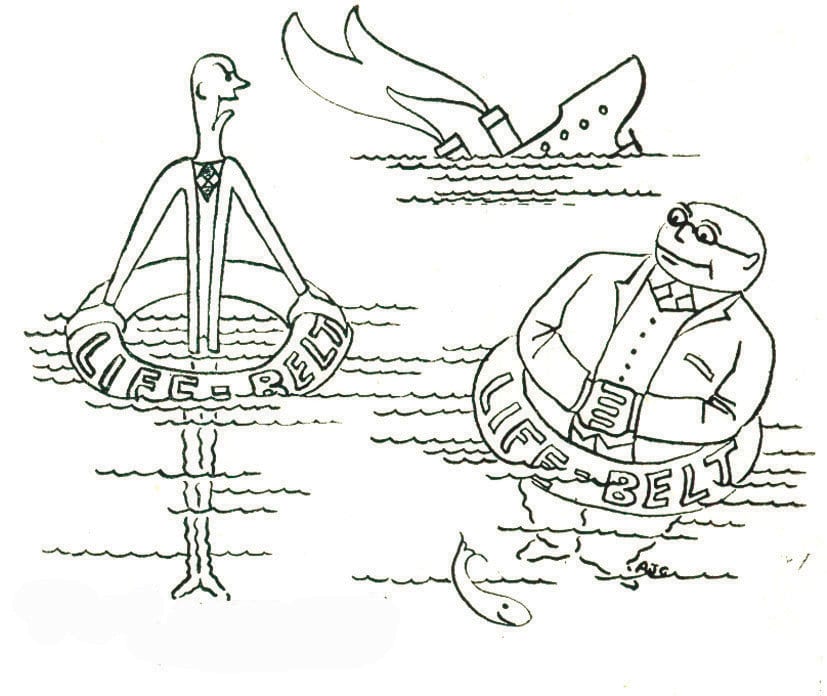

Cartoons from Whitehill School Magazine (1950-52), one of four, courtesy AGA

A

s contributor Scott McNee argues in his essay A Better Nation: Alasdair Gray’s Social Conscience, it is Bella who most keenly demonstrates Gray’s sense of responsibility and concern for societal injustice. Bells is not, however, deaf to the ideologies of others. If we return once more to A Life in Progress we can see this bit of Bella in Gray himself. Exhibiting a characteristic playfulness Gray suggests that ‘Tories could also find something inspiring in [Lee’s] motto’. The comment is both a quip and a thoughtful reflection. The writer’s invitation to better the nation through one’s own occupation or creative act might be mistaken as a glowing endorsement of Conservative Individualism. Knowing Gray, however, we know that is not the case. Rather, Gray suggests that those on the Right could be inspired by the Collectivism that underpins Lee’s lyric. Gray’s understanding that both socialists and Tories could hear the very same motto and interpret its narrative in opposing ways, is very much carried into Gray’s representation of Bella and her interactions with others. Reflecting on this and on Gray’s lifetime commitment to socialism, Scott McNee proposes that ‘it is useful to examine the book for traces of the writer’s social conscience; how it is embraced or rejected by Gray’s characters; how their actions come to shape the world of the novel and to look for a hint of what Gray paraphrased from Dennis Lee: ‘the early days of a better nation’.

A Better Nation:

Alasdair Gray’s Social Conscience

As the manuscript Episodes From the Early Life of a Scottish Public Health Officer begins, considerable focus is given to the social status of its narrator, Archibald McCandless. Initially ostracised by his peers, McCandless rankles against a university lecturer who aptly indicates his ruralclothes and Galloway dialect as the cause of his social alienation. The lecturer proves useless in providing any financial assistance to remedy this – McCandless is made to feel personally responsible for his relative poverty, moments after he tells us he has spent the majority of his inheritance to reach university in the first place.

Only when dressed ‘respectably’, McCandless begins to socialise with his fellow students, who nonetheless enjoy reminders of his origins:

I’m sorry we laughed McCandless, but to hear you steadily quoting Comte and Huxley and Haeckel in your broad border dialect was like hearing the Queen opening Parliament in the voice of a Cockney costermonger (p16)

Their shared experience of being othered by their classmates bonds McCandless and Baxter. Godwin is a man born into immense privilege and access to the medical world, the son of the first knighted medical doctor; and all of this means nothing to teachers, peers and patients who lay eyes on him:

Look at this hand, although of course the sight pains you, this cube with five cones protruding from the top, instead of a kipper with five sausages stuck to the edge. The only patients I am allowed to touch are too poor or unconscious to have a choice in the matter (p40)

Anatomy Museum sketch (1954), courtesy AGA

Godwin is forced to credit his numerous talents to other surgeons, despite the talents of his ‘ugly digits [and] ugly head’ (p40). When McCandless encounters him, he is regarded by the rest of the university as a ‘scientific dabbler’ (p15) and a grotesque sideshow, tolerated due to the shadow left by his father. It is a common feature of modern Gothic novels, such as Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, to focus on marginalised figures like Baxter and McCandless and their strained relationships with wider society. However, Poor Things is vast in scope, and its universe does not revolve around the university. Sympathetic outcasts and poor things as the two friends first appear, they are ultimately the proprietary nature of empire & Capitalism. Ultimately, Baxter and McCandless cannot shake their entitlement as white, respectable Victorian men – they are better than General Blessington, but that entire conflict comes down to deciding which man owns the body of a woman with no say in events.

McCandless is not an underdog, but merely the first sexually mature man that Bella encounters, a man who ‘envied the only two people he loved’ (p273). If we accept Victoria McCandless’ refusal of her husband’s narrative in Episodes, it is also evident that he shaped his wife’s life story for his own benefit, and even entertainment going by the conscious debt his manuscript owes to the gothic genre, as Victoria bitterly notes.

[My] husband's story positively stinks of all that was morbid in that most morbid of centuries, the nineteenth. He has made it significantly stranger still by stirring into it episodes and phrases to be found in Hogg's Suicide's Grave with additional ghouleries from the works of Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filtched from? (pp.272-3)

Baxter’s sympathy-stirring admission ‘the only patients I am allowed to touch are too poor or unconscious to have a choice in the matter’, is quickly turned on its head as he uses it as a justification for bringing Bella to life in the first place, believing he is entitled to the love of something he has created (and humorously, on rejection, his shrill voice finally breaks – an enormous baby finally reaching maturity). McCandless and Baxter experience struggle due to their differences, but as Bella develops into womanhood and begins to articulate her political and social views in an increasingly mature voice, we begin to see a far more extensive study of the Victorian socipolitical climate that has parallels with Glasgow in 1992, and by extension now.

I

t is through the character Bella that Gray most explicitly examines social conscience. As Stephen Bernstein observes, Victoria Blessington dives into the water and emerges as Godwin’s creation Bella, which is reminiscent of Frankenstein’s botched attempt at a female counterpart to the monster, last seen cast in pieces into the sea in Orkney. It is as if these scraps have surfaced, renewed, in Glasgow (p113). Bella’s education in chapters 14-18 (titled ‘Bella Baxter’s Letter: Making a Conscience’, with its own cover illustration) mirror the story narrated by Frankenstein’s creature beginning at roughly the equivalent point (Volume II, Chapter 3) in that novel. The Creature, spying on a family not long after his creation, learns of humanity, politics, art and culture by listening to the son of the family read and discuss Volney’s Ruins of Empires (1792) with his bride-to-be.Volney’s book aims to educate free-thinkers on the world of politics, cultures and nations – both Bella and the Creature do, in different ways, emerge from their education as free-thinkers. Bella learns of the same primarily through the discussions of the cynical Malthusian Astley and the staunchly imperialist Dr Hooker, aboard a ship bound from Odessa to Gibraltar by way of Alexandria. The two men represent competing world views at odds with Gray’s sense social conscience. Contributor, Alex Compton offers her own take on the two characters below.

Character Description: Dr. Hooker & Mr. Astely

Mr Harry Astley and Dr Hooker are travelling aboard a ship around the Mediterranean where they meet Bella and attempt to teach her about how the world works. The English Mr Harry Astley is a Malthusian, believing that the only way to maintain balance and function in the world is by keeping large groups of people in poverty; Dr Hooker is an American Christian eugenicist, believing that the world should be run by white people, such as those from the UK and the US. It is the “Anglo-Saxon” race he believes is superior to other races, such as “Chinese, Hindoos, Negroes and Amerindians” (p.139). This contrasts Bella’s socialist point of view and so, to demonstrate their reasoning, both men take Bella to Alexandria, to witness a group of people begging tourists for money whilst being controlled by men with whips (pp.173-5). This deeply affects Bella, and after the event, both men attempt to comfort her by recommending books relevant to their beliefs – for Dr Hooker, the Bible, and for Mr Harry Astley, Malthus’ Essay on Population. Dr Hooker eventually disembarks, but Mr Astley stays on board longer. Having grown close to Bella, and even proposing marriage, he is turned down by Gray’s heroine before they part ways. In waving goodbye to her two companions, Bella also says a fond farewell to the political perspectives they represent. Bella’s resolve for socialism is consequently concretised.

Written by Alex Compton

Cartoon from Whitehill School Magazine (1950-52), one of four, courtesy AGA

As Hooker explains in Chapter 15 to a mostly (at this point) silent Bella, his worldview is strictly paternalistic and intensely categorised by crude stereotypes – his lessons to Bella are full of references to ‘talkative French’, ‘carefree [and murderous] Italians’, cannibalistic Africans and Chinese torture, all aspects of ‘childish people’ who require ‘policing’ and ‘civilising’ from the divinely-gifted Anglo-Saxon until they can be trusted as human beings (p139-141)

In a recording from Gray Day 2023 - an annual celebration of Alasdair Gray’s life and work - journalist and author Chitra Ramaswamy reads from Chapter 15 and reflects on her experience of re-reading the novel after two decades - an exercise which brought Gray's colonial critique into sharper focus. To listen, click on the playbar below.

Recording from Gray Day 2023 Live featuring Chitra Ramaswamy, 25 February, Òran Mór, Glasgow, courtesy AGA

In Gray's scene, Bella is both Creature and woman (Safie). Initially won over by Hooker’s offer to teach her to play chequers, she is as rapt as both characters listening to Felix’s readings. The exoticized foreigner (and thus a safe, understandable, kind of ‘other’) Safie is a beautiful marriage prospect choosing to learn about culture and politics in order to enter the Western world as an acceptable bride. Bella is also mirrored in the hideous, dangerous other of the Creature, whose learning leads him to attempt to reach out as an intellectual equal and is doomed to violent rejection. (The Creature’s distrust after this experience early in life is somewhat reminiscent of Astley, a sensitive man made performatively cruel by an emotionally neglectful upbringing, though of course, as landed gentry Astley is safely cynical and suffers no social repercussions). Safie faces assimilation into Western hierarchy, while the Creature resents his lack of a place in it. Reflecting Gray’s own social conscience, Bella is the pupil who almost instantly begins to question the power structure and think of improvement.

I heard of the slothful Asiatics; of the stupendous genius and mental activity of the Grecians; of the wars and wonderful virtue of the early Romans

The lines you will have heard Ramaswamy speak - 'talkative French’, ‘carefree [and murderous] Italians’ - closely mirror a scene from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, where the Creature eavesdrops on the Volney lectures Felix delivers to fiancé Safie:

Each time Bella encounters the horrors and inequalities of the world, we are baited with the birth of a cynic that never occurs. The ‘innocent’ mind that Dr. Hooker seeks to educate in his racist fantasies, and Astley initially wishes to spare from knowledge, always turns towards empathy, able to recognise the clishes of her privileged companions as just that. If we were hoping for a true Frankenstein pastiche, there is, sadly, no moment where Bella (or Godwin, being the physical grotesque) embarks upon a murderous rampage. Bella never loses the Creature’s natural empathy through trauma: ‘I thought (foolish wretch!) that it might be in my power to restore happiness to these deserving people’ (Shelley, 1818). Instead, the ‘creature’ of Poor Things undergoes a far more optimistic transformation, emerging from the ships as a socially conscious woman who will eventually be known as Dr Vic, ‘active suffragette [and] Clydeside Socialist’ (p305).

Dr Hooker is a poor match for Bella’s emerging social conscience, unable to provide any rebuttal for Bella’s observation that Jesus’ teachings contradict Hooker’s own political beliefs and actions, especially his refusal to assist the poor (‘YOU CAN DO NO GOOD!’ (p174), he yells as she is caught in the throng in Alexandria). His hypocrisy exposed by the level of child’s logic, he disembarks from the ship under Bella’s summary that ‘He does not want to live by the teachings of Jesus… but dare not say so’ (p153). It is in Harry Astley that Bella finds a more fitting opponent and worthy teacher. In ‘Astley’s Bitter Wisdom’ we are presented with various lecture topics as Astley struggles to bring Bella round to his point of view, or at least limit her desire to do good to a small scale – in its most reductive form ‘[wanting] to persuade [Bella] that bad is needed’ (p154). Astley argues for the inevitability of the status quo regardless of nation or race, remarking that despite the power of the British Empire, he expects ‘the half-naked descendants of Disraeli and Gladstone may be diving off a broken pier of London Bridge, retrieving coins flung into the Thames by Tibetan tourists who find the sight amusing’ (p161). Through Astley's reflection about the British Prime Ministers he predicts the fall of the Empire against a new one, be it Tibetan or otherwise. The politics of empire building was a repeated point of interest for Gray's wider, most notably in his epistolary short story Five Letters from an Eastern Empire published in Unlikely Stories, Mostly (1983) and in his poem Dictators.

Dictators audio recording (2007), courtesy AGA. The poem was included in Alasdair Gray 'Collected Verses' published by Two Ravens Press, 2010

For Astley, all of human history is a cycle of Empires – every nation is equal in the sense that they will inevitably dominate and plunder if given the advantage. He links this to humanity’s most enduring stories, that dominance is reflected in the championing of Achilles and Odysseus and the Trojan War. Of course, this is interpretation used as confirmation of cynicism – one could easily argue that as much as they can be seen as a celebration of will and slaughter, Achilles and Odysseus are as equally motivated by love, for Patroclus and Penelope respectively. Astley’s arguments serve chiefly as a reason to remain inactive. Political change is impossible, he argues, which both depresses and benefits him as a rich businessman. In his education of Bella, his cynical ‘truth-tellings’ serve as a mask for his true aim, which is to share his misery with another human. When his arguments prove fruitless, Astley instead asks for Bella to hold his hand:

So I did and I felt for the first time who he really is – a tortured little boy who hates cruelty as much as I do but thinks himself a strong man because he can pretend to like it. He is as poor and desperate as my lost daughter, but only inside. Outside he is perfectly comfortable. Everyone should have a cosy shell round them, a good coat with money in the pockets. I must be a Socialist. (p164)

Again Bella’s naked empathy defeats something that seems intended to direct her toward cheap cynicism. Much like Godwin’s misdirected unhappiness with his own appearance, Astley’s political beliefs are misdirected depression and despair, twisted into a poor justification. At the same time, there is a deep sense of melancholy for the reader. It is a despondency that is unabated whether we accept or reject McCandless’ “truth” in Episodes and Gray’s inference in the Introduction and Notes that Bella Baxter transforms into Dr. Victoria McCandless MD. Having encountered Gray’s framing device with Donnell, Bella’s hopes for the future are dead. The socialists of the Labour Party that Bella (as Victoria McCandless) allies herself with during the First World War have been pushed out of the mainstream by 1992, and Gray and Michael Donnelly live in a country governed by Astleys – as he himself predicted, socialists elected to parliament will be ‘outwitted… or bribed, or compromised into nonentity’ (p162), because parliament is an institution created solely to protect hoarded wealth.

Earlier in Bella’s development, she has her first encounter with politics which will inform her actions for the rest of her life. Bella’s first encounter with socialism, and indeed the wider political landscape, is through the satirical Punch magazine, a context that causes her some initial confusion while trying to develop her own opinions on the world:

The pictures showed many kinds of people. The ugliest and most comical are Scots, Irish, foreign, poor, servants, rich folk who have been poor until very recently, small men, old unmarried women and Socialists. The Socialists are ugliest, very dirty and hairy with weak chins, and seem to spend their time grumbling to other people at street corners (p127)

In the poor tradition of British satire, Punch serves to uphold the establishment – its comic potential mocks the absurdity of anything that is not White, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. Here, Gray is mocking, laying bare the magazine’s agenda by merely noting its content at length; comedy that, as Chris Morris remarked, exists ‘trying to do something exotic for the court, to be patted on the head by the court’ (Morris, 2019).

The Book of Prefaces, interior title page (2002), courtesy AGA

The exposure to representations of while her child’s brain has yet fully to develop proves quite unfortunate for Bella, who is yet to get past the stage of parroting information she receives without critical thinking: ‘Punch says only lazy people are out of work so the very poorest must enjoy being poor. They also have the consolation of being comic’ (p135). Bella's trait of parroting still remains during her discussions with Astley, as she identifies with socialists, then communists, violent anarchists, and pacifistic anarchists in turn as Astley mentions them. It is only when given some time to think for herself that she comes to the realisation that she is a socialist, as quoted above. The Bella from this point onwards is far more decisive. The record of Bella’s later life as Victoria McCandless MD (recorded by Gray in Notes) details her split from the progressive Fabian society over its relative inaction and implicit support of the First World War, and lengthily covers the legal battle surrounding the Natal Clinic (‘a Bolshevik charity!’ according to The Daily Express) that surreptitiously performs abortions for women in need (p310). The records from the time period show that the institutional attitude towards socialism has not changed – the ‘Loving Economy’ Victoria McCandless is a threat to the wealth hoarding and performative cruelty that Astley warned of. The difference is that Victoria is now completely open in her battle for change, a prolific political writer and activist who refuses to bend under the weight of controversy and the law, even with her erstwhile political allies, such as the ‘orthodox’ communists she argues with. She has supplanted McCandless, such an influence on her early life, a non-entity now that she is fully formed. And once again, Gray reminds of the present day – a life of this fame, controversy and empathetic deeds is nothing more than ‘a name only known to historians of the suffragette movement nowadays’ (px). A life well-lived, but just as unable to stop the neoliberal machine from forming as Astley predicted.

Is Scotland a Possible Nation (2014), courtesy AGA

Character Prompts

Mr. Astely and Dr. Hooker

What political perspectives do Dr Hooker and Mr. Astley represent?

What is meant by the quote “Anglo-Saxo race he believes is superior to other races, such as “Chinese, Hindoos, Negroes and Amerindians”

How do Dr Hooker’s and Bella’s opinions clash?

How does Dr Hooker and Mr Astley inspire Bella’s ideas going forward and change her direction?

Get involved! Share your response to the promts using #PoorThings

Prompts written by Grace Richardson and Janaki Mistry