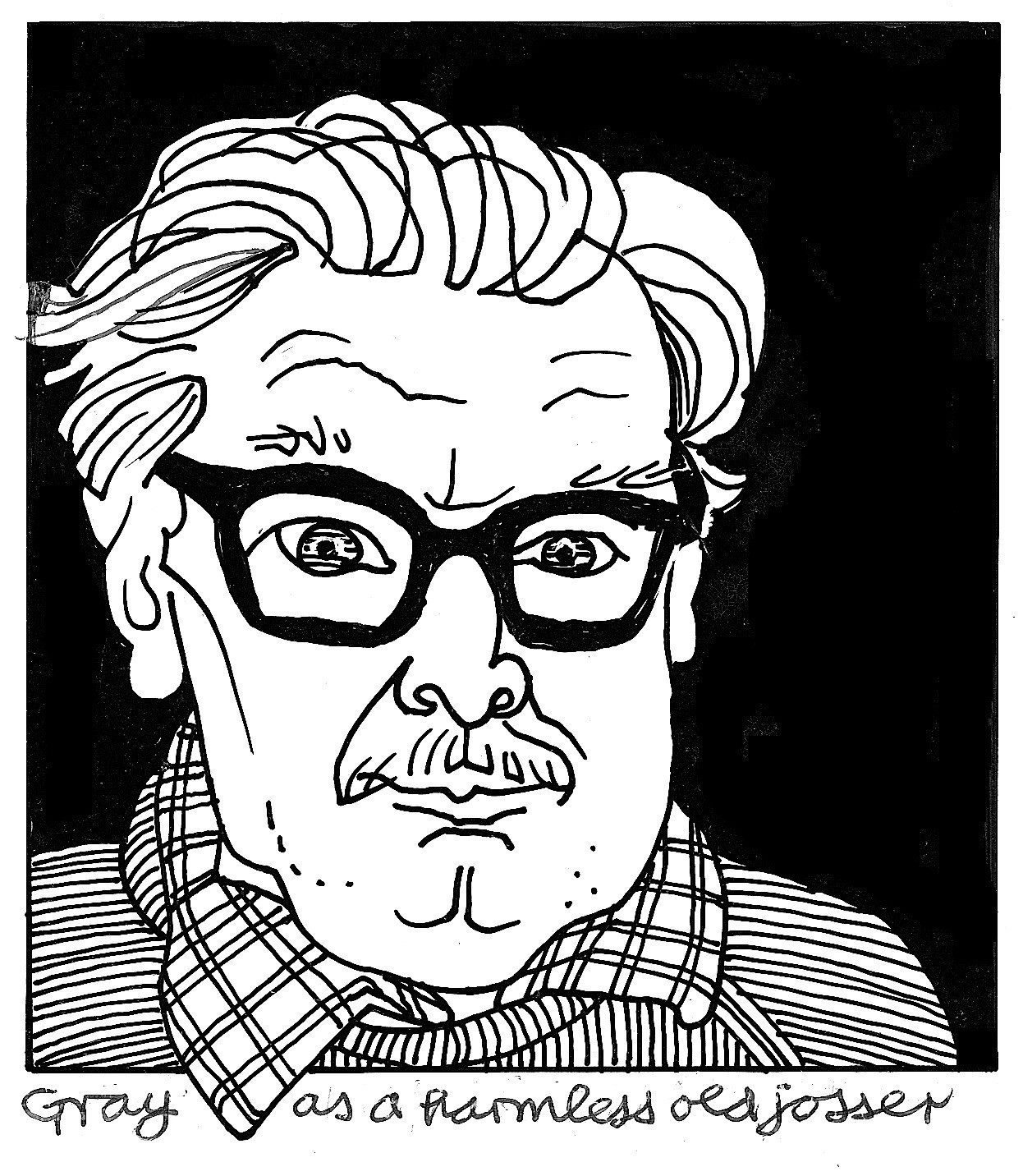

Self-Portrait by Gray from Letter to Robert Kitts (1955), courtesy AGA

Profile

Gray-the-Editor

In the introduction to Poor Things (1992), Gray does not present himself as the author of his novel, but as the editor of a work of non-fiction. Poor Things is compiled from memoirs written and published by Archibald McCandless in 1909 he claims. Gray has merely edited those memoirs after they were discovered by historian Michael Donnelly. All Gray did to further enhance the work was to compile some historical notes and - oh yes - attach a letter from the deceased doctor's late wife, Victoria McCandless, refuting the entire contents of her husband's book. A likely story...

It is, of course, up to you whose narrative to believe. You may find it useful, however, to differentiate the character Gray-the-Editor, who claims to have found McCandless' memoirs, from Alasdair Gray the real author of Poor Things. Yet, the line between Gray-the-Editor or ‘Gray’ - a typographic marker devised by Neil James Rhind to differentiate the character from the author – is not always clear (Rhind, 2009). And this is part of the novel's great fun.

In his role as editor 'Gray' commands significant sway over how the material is presented to the reader. An editor is, after all, responsible for the final contents of a published work, including the order of its different units. We shouldn’t forget that the order of the sections within a written work – be it a poetry anthology, an essay collection, or a novel – create a structural framework that contributes to the reader's overall comprehension of the text's central concerns.

Now here comes the fun bit. Imagine for a moment that Victoria's 'letter to posterity' appears at the beginning of the novel as a preface to her husband's book (rather than just the passing mention of it in the Introduction). Would its placement within the order of the volume not change the way you thought about Archie's claims? Would reading the letter first have inhibited your ability to believe in Archie's fantastical but equally compelling account of the life of Bella Baxter? Yes? No?

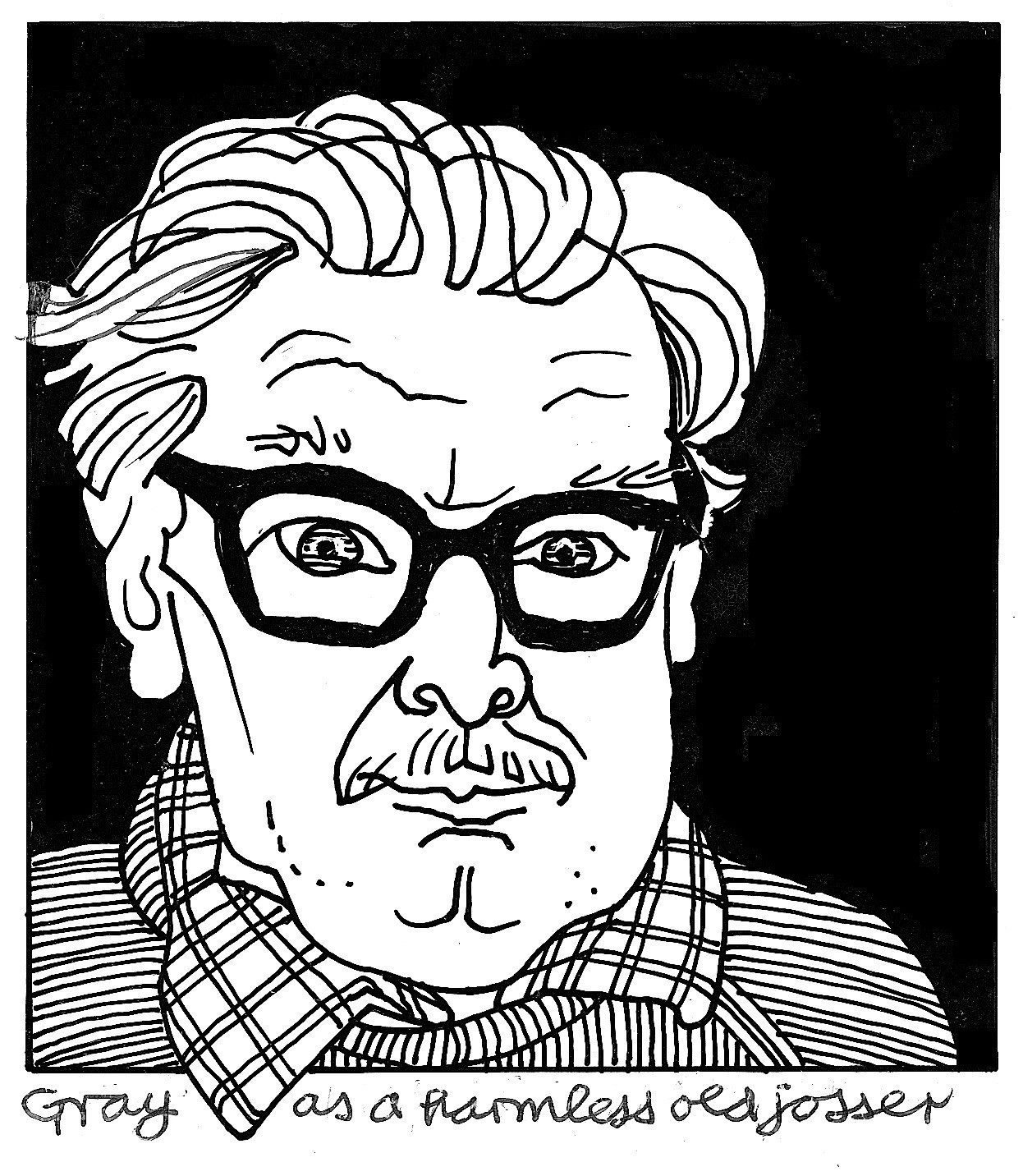

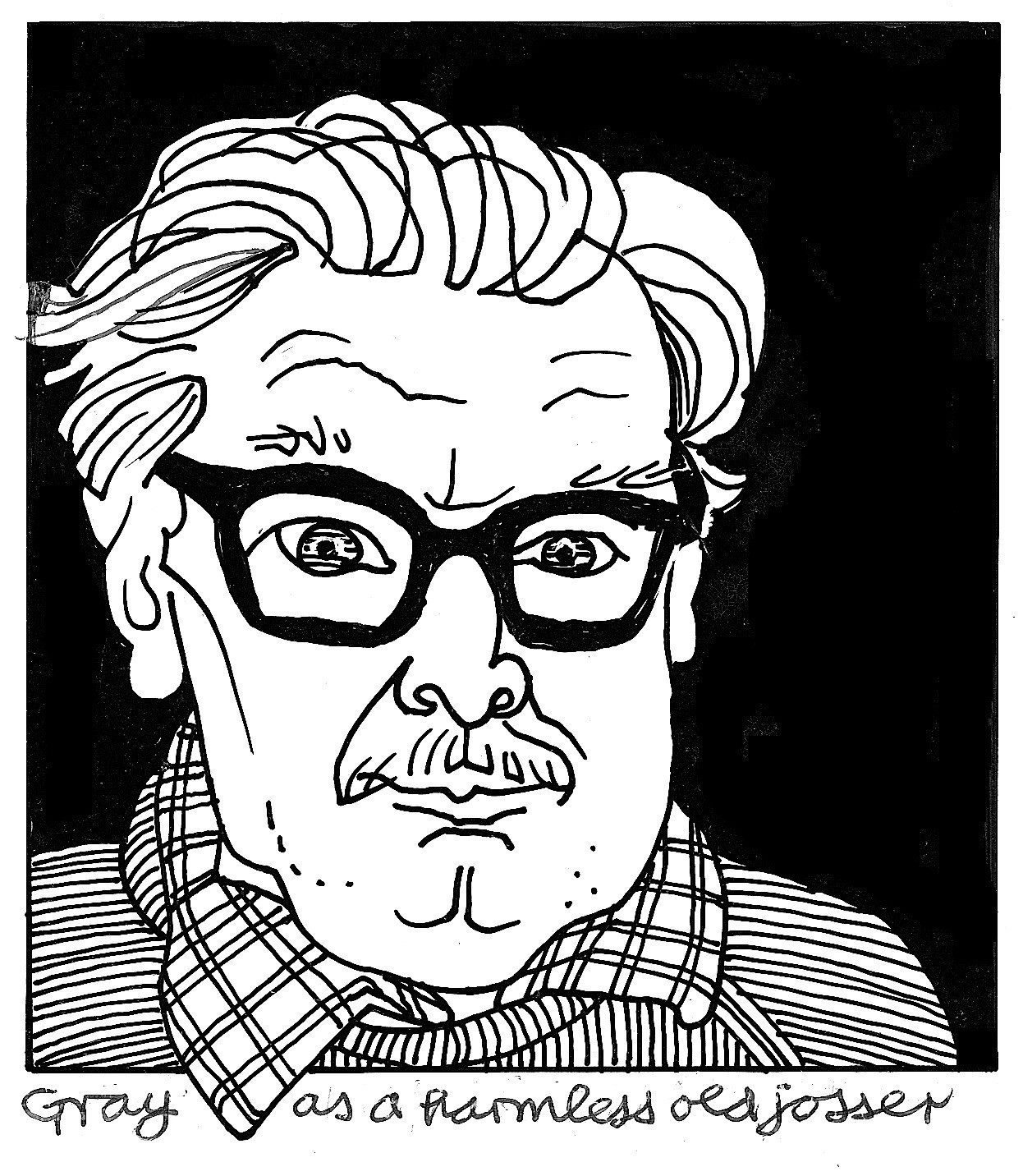

Well, how about this for an answer: simply put, Gray-the-Editor's control over the structure of the text enables him to shape the reader’s reception. In doing so, he cunningly attempts to establish himself as the volume’s primary truth-teller. And for us as readers, that also means trying to keep up with Alasdair Gray's cunning ploys to fool us. (He is after all the writer behind his fictional self). So much for being 'a harmless old josser', eh?

One such example of his cunning is this: in an attempt to lay claim to the impartiality of his editorial choices 'Gray' (with a healthy dollop of indignance) claims that his readership is not bound to the narrative framework he has set out for them: 'Readers who want nothing but a good story plainly told should go at once to the main part of the book’, ‘Gray’ states. ‘Professional doubters may enjoy it more after first scanning this table of events’ (pXIV).

In theory, readers can engage in a choose-your-own-adventure style narrative by starting at whichever section of the volume they wish.

The offer is, of course, a rouse. Be you a professional doubter or fiction-enthusiast, after pulling Poor Things off a bookshelf for the first time, how many of you read the novel in anything but its intended order?

Gray as a Harmless old Josser (1990), courtesy AGA

To listen to an extract from the Introduction we've just been discussing, click on the playbar below. Gray's biographer, Rodge Glass, will meet you there.

Recording from Gray Day 2023 Live featuring Rodge Glass, 25 February, Òran Mór, Glasgow, courtesy AGA

Profile

Gray-the-Editor

In the introduction to Poor Things (1992), Gray does not present himself as the author of his novel, but as the editor of a work of non-fiction. Poor Things is compiled from memoirs written and published by Archibald McCandless in 1909 he claims. Gray has merely edited those memoirs after they were discovered by historian Michael Donnelly. All Gray did to further enhance the work was to compile some historical notes and - oh yes - attach a letter from the deceased doctor's late wife, Victoria McCandless, refuting the entire contents of her husband's book. A likely story...

It is, of course, up to you whose narrative to believe. You may find it useful, however, to differentiate the character Gray-the-Editor, who claims to have found McCandless' memoirs, from Alasdair Gray the real author of Poor Things. Yet, the line between Gray-the-Editor or ‘Gray’ - a typographic marker devised by Neil James Rhind to differentiate the character from the author – is not always clear (Rhind, 2009). And this is part of the novel's great fun.

In his role as editor 'Gray' commands significant sway over how the material is presented to the reader. An editor is, after all, responsible for the final contents of a published work, including the order of its different units. We shouldn’t forget that the order of the sections within a written work – be it a poetry anthology, an essay collection, or a novel – create a structural framework that contributes to the reader's overall comprehension of the text's central concerns.

Now here comes the fun bit. Imagine for a moment that Victoria's 'letter to posterity' appears at the beginning of the novel as a preface to her husband's book (rather than just the passing mention of it in the Introduction).

Would its placement within the order of the volume not change the way you thought about Archie's claims? Would reading the letter first have inhibited your ability to believe in Archie's fantastical but equally compelling account of the life of Bella Baxter? Yes? No?

Well, how about this for an answer: simply put, Gray-the-Editor's control over the structure of the text enables him to shape the reader’s reception. In doing so, he cunningly attempts to establish himself as the volume’s primary truth-teller. And for us as readers, that also means trying to keep up with Alasdair Gray's cunning ploys to fool us. (He is after all the writer behind his fictional self). So much for being 'a harmless old josser', eh?

One such example of his cunning is this: in an attempt to lay claim to the impartiality of his editorial choices 'Gray' (with a healthy dollop of indignance) claims that his readership is not bound to the narrative framework he has set out for them: 'Readers who want nothing but a good story plainly told should go at once to the main part of the book’, ‘Gray’ states. ‘Professional doubters may enjoy it more after first scanning this table of events’ (pXIV).

In theory, readers can engage in a choose-your-own-adventure style narrative by starting at whichever section of the volume they wish.

The offer is, of course, a rouse. Be you a professional doubter or fiction-enthusiast, after pulling Poor Things off a bookshelf for the first time, how many of you read the novel in anything but its intended order?

Gray as a Harmless old Josser (1990), courtesy AGA

To listen to an extract from the Introduction we've just been discussing, click on the playbar below. Gray's biographer, Rodge Glass, will meet you there.

Recording from Gray Day 2023 Live featuring Rodge Glass, 25 February, Òran Mór, Glasgow, courtesy AGA

Although Gray-the-Editor tells us in the Introduction about Victoria's claim that 'the book is full of lies' (pX, his preface to the novel works hard to convince us otherwise. The Introduction's 'table of events’ offers one such example (pp. XIV-XV). As critic Lila Ibrahim points out, this historical timeline not only presents fiction as fact in its content and style. It also highlights the similarity between the fictional ‘Gray’ and Alasdair Gray, the author. ‘Gray first published Poor Things in 1992’ Ibrahim writes, ‘and ‘Gray’s’ description of how his edited book came to be published would also put it around 1992’ (Ibrahim, 2015, p8). This classic josser move from Gray, is also a literary technique. See the note critical below...

But wait. There are more doppelgängers in store. In addition to 'Gray'/Gray, another fictive/non-fictive identity is seen in ‘Donnelly’/Donnelly. The novel’s local historian Michael Donnelly, like Gray-the-Editor, is a real-person siphoned into character form.

Note Critical

Another term for the crossover between Gray and 'Gray' is self-referentiality. It's a technique that is associated with Post-Modern writers (a label that Gray repeatedly rejected) and is a key feature of Gray's style, which has been compared to Franz Kafka, Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino. Gray's Post-Modernist traits are particularly evident in his para-texts (his introductions, epilogues, end notes, and footnotes) and in his authorial intrusions (for example Lanark’s ‘Epilogue’) Other features of Post Modernism present in Gray’s writing include the rejection of stable identities and hierarchy in exchange for pluralism, irony, irreverence and self-referentiality.

Note Historical

Alasdair Gray, the real-life Michael Donnelly and the curator of the People’s Palace, Elspeth King, shared a successful working relationship. In 1977-78, the artist was commissioned by King and her assistant, Donnelly, to produce the City Recorder Series for The People's Palace. With additional support from painter and sign-writer Robert Salmon, the trio collaborated again in 1994-96 on a mural in Abbot's House local history museum in Dunfermline.

Tree of Dunfermline History: Abbot's House Ceiling (1994-96), courtesy AGA

For contributor, David Hasson it is not only Gray and Donnelly who are siphoned into characters. In his contribution below, he argues that Glasgow - the city where Gray lived, worked and set many of his novels including Poor Things - wears an equally compelling disguise.

Gray as a Harmless old Josser (1990), courtesy AGA

Curmudgeon (noun)

A person was much prone to exasperation, which the non curmudgeon often mistakes a bad temper. (Often portrayed as old: the wiser you get the more prone to exasperation you become).

Gray wrote a lot of characters as curmudgeonly creatures. In some lights and in some encounters Alasdair himself was curmudgeonly. I think this applies to every character in Poor Things including the way Alasdair portrayed himself. He portrayed (as opposed to invented) two other curmudgeons: Michael Donnelly and the City of Glasgow. The latter of course is a common character in his work, often in disguise. We know her too well to be fooled by the various guises he finds for her.

Of Michael perhaps we should say that the source of his exasperation was Alasdair. He is a tool of the God (win) like ability of the author to make of him what he will. Probably he was a kind-hearted and patient soul, but it was better for the story if he could be said to disagree about the book, and even be portrayed, albeit slyly, as being in a huff about it. Then the exasperated assertions of the historical truth of the story Gray makes can be proclaimed even louder than is really necessary.

Glasgow has two disguises that Gray clothes her in, both historical. The second is the period where she was being very roughly treated: the 1970’s. She was in danger of having her whole character not so much stripped away as simply oppressed. She nearly became an ordinary example of banality, engendered by misconceived notions of modernity. She spat out fragments of herself, bits of coloured glass, parts of fountains and so on. It was a curmudgeonly challenge: “go on” she seemed to be saying, “find coherence in all that junk. Tell my story. I dare you”. The poor thing…

Michael (by helping Elspeth King, who only gets a small part: she deserves more) tried. And then as if by chance a fragment that was a coherent story was presented to him. It was twice snatched away. They were papers from the solicitor’s office left in a Glasgow street. Snatched away as he was forbidden to collect and review them. Thank goodness he stole that little book: the memoirs of Archibald McCandless M.D. That too was snatched away, much to his exasperation, by Alasdair.

The first disguise Glasgow in Poor Things has was as a proud, coherent and powerful city: that 19th century bastion of imperial stolidity and enterprise that was the second city of the empire. In any case that is how she was disguised. Her exasperation at that was perhaps greater. Alasdair tries to tell her story as he found it, to reveal at least some of the truth. I for one don’t doubt that had the other papers from the solicitor’s office been preserved all the documentary proofs Michael needed to see would have been found. The snobbishness cruelty and narrow mindedness of her people didn’t prevent the achievement of great things, especially in this time. But Glasgow was never defined by these, any more than by the ravages of the 1970’s. Once again she throws out fragments: the character of her grander domestic spaces, the parks, her universities, and the stories of the great things achieved there in medicine and science. But there is the insistent voice of the city saying: “show me truthfully: I am cruel, why else are so many souls suffering? Why else does a young women with child fling herself off one of my more picturesque bridges? I am a monster, but a monster with a great ridiculous humanity”. The great cry of her Godwin is the exasperation of a monstrous thing not understood or loved as she should be.

So: Alasdair and Michael and Alasdair are both exasperated in the story of “The Poor Things” because they both think they are the voice of Glasgow. The greatest curmudgeon, Glasgow herself, knows that they are just two of the voices we need to hear if we are to understand the great sound of humanity that is the Poor Things true voice.

Written by David Hasson

Michael Donnelly: Elspeth's Assistant (1977), courtesy AGA

So, what can we extract from these many disguises? Well, many things. But here's one: ‘Gray’/Gray and 'Donnelly'/Donnelly are literary devices that foreground the novel’s multiple conflicting narratives. In turn, this illuminates Poor Thing’s interest in the subjective ways in which historical ‘truths’ have been recorded.

In the next chapter of Poor Things: a Novel Guide, you'll meet Gray's surgical genius, Godwin Baxter. As you will discover, Godwin Baxter is - at least in part - another of Gray's disguises in Poor Things. To go now with Godwin Baxter click on his image below. To meet him after first learning about Gray's tendency for blending fact and fiction in his self-representation outside of his written work, scroll below.

In the introduction to Poor Things Gray-the-Editor disputes ‘Donnelly’s’ claim that McCandless’ memoir is a ‘grotesque fiction’ into which 'some real experiences and historical facts have been cunningly woven’ (pXII). (It’s important to remember this phrase. We’ll come back to it when we discuss Gray’s habit of self-fictionalisation within his non-fiction writings and interviews). It should be fairly evident that Donnelly is correct. Poor Things is a ‘grotesque fiction’, in that it draws from Gothic tropes. The novel’s content and notes blend fact and fiction throughout. It should also be clear to see that by including the fictional Donnelly’s opinion ‘Gray’ undermines his own argument (which opposes Donnelly’s).

Curiously, a similar pattern can be seen in Gray's wider body of work. As Neil Rind argues, ‘Gray’s attempts at enticing the reader to certain conclusions shading into a coercion […] is blunted through undermining the sermonizer’s authority' (Rhind, 2009, p17). One way this can be seen is in Gray’s interview style, which is characterised by the writer's deliberately evasive, sometimes playful, often subversive responses to his interviewer's questions. ‘Gray’s pseudo-posthumous BBC documentary Under The Helmet (1964), for example, offers an exaggerated example of 'Gray’s play with interviews’ (Rhind, 2009, p17). Rhind also points to 'the camera trickery' of Kevin Cameron’s documentary film about Gray, A Life in Progress (2014) in which the author interviews himself in a thinly veiled guise. Watch an excerpt from the film below to judge for yourself.

A Life in Pictures (2014), directed by Kevin Cameron, courtesy AGA

In Under The Helmet, Gray's guise is arguably more convincing. Within the first 5 minutes of the documentary - which is billed as 'a tribute to an unknown artist...destined to be unfinished' – we see cutaways of Gray's undisturbed studio. A solo trumpet mournfully wails. The audience believes that the artist is dead.

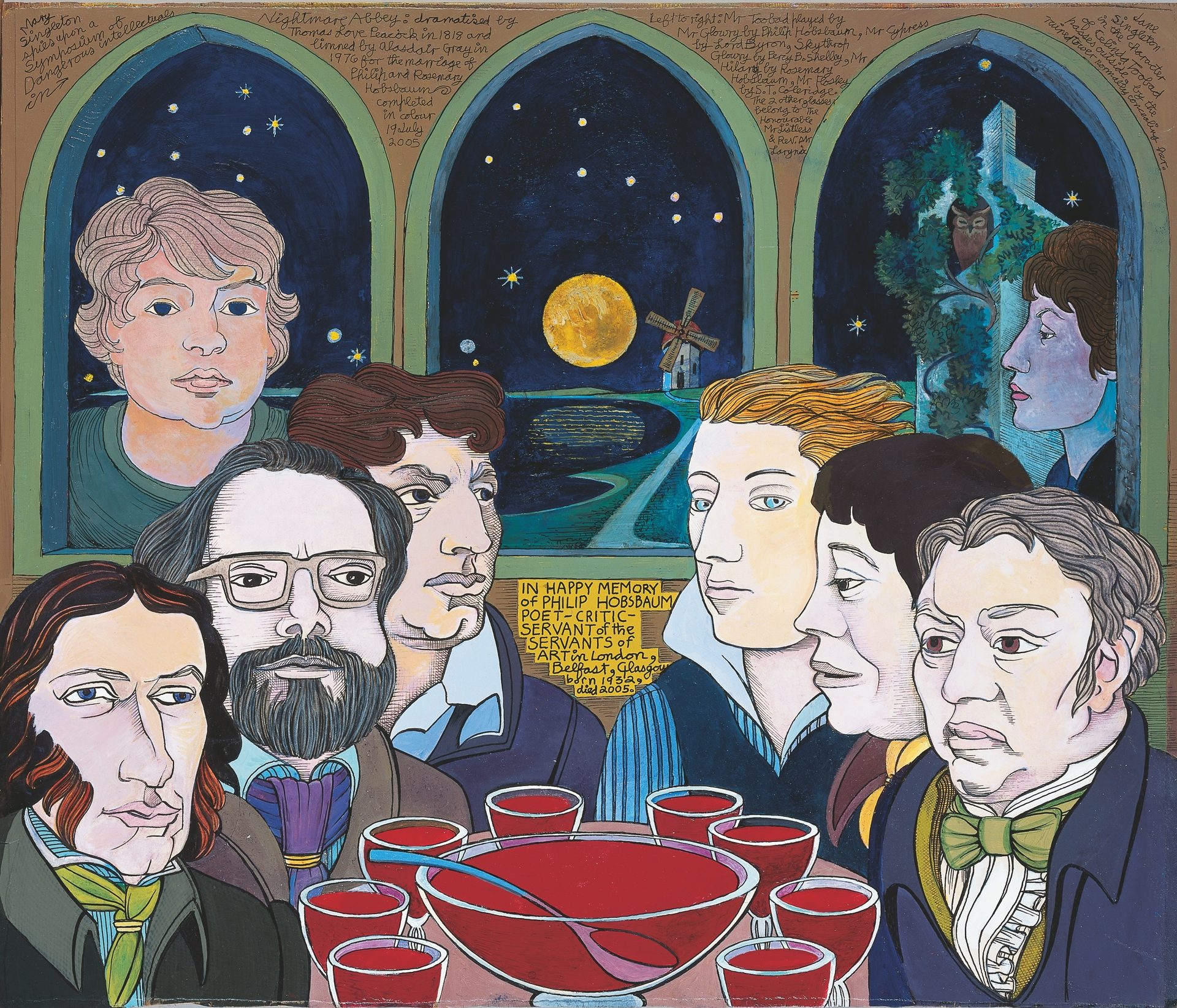

Gray’s experience recording Under The Helmet, spawned another creative work that blends fact and fiction. The writer's trip to BBC London inspired his television drama The Fall of Kelvin Walker: A Fable of the Sixties (1968). He adapted the drama into a novella in 1985. The Canongate edition of Kelvin Walker is prefaced by an interview. As you may have guessed the interview, which was hosted by Mark Axelrod and published in full in The Review of Contemporary Fiction (Summer 1995, Vol. 15.2), offers another example of Gray's idiosyncratic interview style. The excerpt included in the Canongate showcases the writer's attempt to entice his readers to make 'certain [and somewhat misleading] conclusions' about his motivations for re-writing the politically charged Kelvin in mid 1980's. Now I know you may be desperate to READ THE INTERVIEW IMMEDIATELY, and if that really is your want, wish and desire, you'll be whisked right to it by clicking below on that friendly looking man in the midst of falling into a bottomless hell*.

The 'hullo', I need not mention, is addressed to all of you whose wishes, wants and desires culminated, like Kelvin's, in rather a swift fall. I gather all is well after your trip? Excellent. Since I've got you back - and you look like you could do with a rest – I would suggest we linger a moment longer NOT on the actual fall of Kelvin Walker, but on the novella's title. Please note: you are not being coerced. I do suggest, however, that professional doubters and fiction-enthusiast alike may enjoy the interview that prefaces Kelvin a little more after first scanning the sections below.

Hullo Again

Second things first. We shall begin our exploration of Kelvin Walker's title not with its allusion to the river Kelvin in Glasgow, but with its subtitle: 'A Fable of the Sixties'. Now, first things first, we ought to begin by asking a simple question:

Q: What is a fable?

A: You are absolutely right. It is a literary genre of fiction, usually short in length, which illustrates a particular moral lesson.

(And yes. You are again absolutely right to say that fables tend to involve anthropomorphized beasts, but not in this case).

Fables have influenced Gray's creative thinking from childhood and remained a constant companion throughout his career as he explains in a 2012 Scotsman article, appropriately though not succinctly titled, ‘Alasdair Gray explains how his love of fable never left him as he grew up'. In his 2010 autobiography A Life in Pictures, he repeats much the same story: a working-class boy from a Glasgow housing scheme escapes his hum-drum life through the stories and pictures first made available to him through the encouragement of his Socialist father. The fabulists that influenced the boy – Hans Christian Anderson, AA Milne, Rudyard Kipling, Lewis Carroll – are just some of the writers whose fantastic tales young Gray uncovered on the ‘middle shelf of [his parent’s] bedroom bookcase’ or in Riddrie Public Library. The quotation above is drawn from Lanark’s ‘Tailpiece': a Q & A both written and answered by the author. It echoes the story Gray recounts in The Scotsman, and in A Life in Pictures, and through Lanark's protagonist Duncan Thaw.

Q: But what’s that got to do with anthropomorphized beasts?

A: The answer is nothing. Absolutely nothing.

Working Legs: A Play for People Without Them, illustration (1997), courtesy AGA

What that's got to do with is more keenly related to the root meaning of fable. Historically, the word fable has referred to an invented incident or fictitious tale. It comes from the Latin fabula, ‘story’, and fari, ‘speak’, an etymology that alludes to its place within oral storytelling traditions. To 'speak a story', we might thus interpret as to 'tell tales'.

Q: Wait a minute! Are you implying that Gray made all of this fable-childhood-inspiration stuff up?

A: No, I am not. What I am suggesting, however, is that by sharing the same genesis story across several years and several texts (at times verbatim), Gray has cultivated his own fable-like narrative. Its aim, I am suggesting, is to shape the reader’s response to the underlying themes and concerns in his work. Although I’ll leave you to work out the moral lesson….

Q: That publicly funded libraries are essential in creating an egalitarian (preferably Socialist) society where access to education is not affected by class status or wealth inequality?

A: An interesting observation...

Q: Still nothing to do with anthropomorphized beasts though?

A: Absolutely nothing.

What Gray's fabulist interests emphasise are his repeated strategies of a.) framing the reader's response through carefully constructed paratexts and b.) developing innovative means of both posing and responding to questions that he wants to be asked and wishes to answer.

Readers should now feel free to read the interview that prefaces The Fall of Kelvin Walker (1985) below. Keep your eyes peeled for fables, coercions, evasions and playfulness.

Note Critical

If any section in the following excerpt happens to be, say, highlighted or underlined feel COMPLETELY FREE not to perceive those particular lines of any more importance than the rest of the text.

Interview: Alasdair Gray & Mark Axelrod

Mark Axelrod: What was the genesis for Kelvin Walker? What were the political reasons for writing it?

Alasdair Gray: Kelvin Walker was first written as a television play in 1965 but had more than one origin. The first was a scene I imagined in 1959 or 1960 in which a dour dependable Scot of the technician type (like [the protagonist of 1982 Janine] Jock McLeish) is bullied into sharing his home with—and by—a Bohemian artist with a very attractive girlfriend. The plot was to be the seduction of the girl by the apparently quieter, more ordinary man after a violent quarrel between her and the man she mainly loved. But all I got written was a fragment of the scene where this happened because I could imagine no interesting social setting.

Around the same time, I was accosted—twice in a cafe, once in a hospital waiting room—by strangers who said, “Excuse me, but would you mind if I engaged you in conversation?” and went on to tell something weighing heavily on their minds at the time. Their stories were different but began with the same formal Scottish inquiry. Then I read a literary magazine containing a scene from J. P. Donleavy’s Fairy Tales of New York: one in which a young man whose only talent is verbal adroitness talks himself into a high position in a New York corporation. And then in 1964 I got a telegram from a friend in the London BBC, telling me to phone him, reversing the charges. I had no telephone then, was living on the social security dole with my wife and our one-year-old son, working at painting except when too depressed to paint, when I would work on Lanark. I phoned the friend, Bob Kitts, who had become a TV documentary director on an arts program called Monitor. He had persuaded his boss (Huw Weldon) to let him make a forty- five-minute film about an almost wholly unknown poet and painter—me.

He arranged for me to leave the Sauchiehall Street labour exchange (where I had to sign in punctually once a week), go by taxi to Glasgow airport, collect my tickets at the B.E.A. desk, fly to London, and be met by a glossy Daimler, which drove me at once to the headquarters of BBC television, when Britain had only one TV channel, and that was it. So from being a state supported pauper, I became simultaneously a Scot on the Make in London who felt himself on the verge of Wealth and Fame. I did not get them: but I suddenly imagined Kelvin Walker with his Nietzsche inspired conviction that invincible self-confidence, a clear head, and a sharp tongue could get him onto the social ladder a few rungs from the top. Bob’s television film did not get me the mural commissions I hoped for but paid me enough money to live by doing what I wanted for twelve months or more, and in that period I wrote the television version of The Fall of Kelvin Walker, which was broadcast by London BBC in 1968 (though bought two years earlier) and published as a novel in 1985: when a Scottish BBC TV producer invited me to lunch and explained that he thought it would make a splendid television play.

As to my political reasons for writing it—I had none at all. The politics of any story I tell are the politics of the country where I live. The prime minister and newspaper owner in Kelvin Walker were as necessary to it as King Arthur and Merlin to a medieval romance. I was told later that many on the BBC thought Kelvin Walker was based on David Frost, but I had never seen Frost. I did not own a TV set in those days.

Hold on a second. Did you read the interview in full? I suspect there are a few readers of the scanning variety out there… Well, no harm done. Even just by scanning the page, it’s clear that Gray’s answer takes the form of a narrative. The central section offers two lengthy anecdotes (also recounted in A Life in Pictures). And if you did read the text, you might have noticed that both sidestep Axelrod’s two pronged question: what was Kelvin’s genesis? And what was its author’s political motivation for writing it? The implication behind Axelrod’s enquiry is, of course, that the novella originated from Gray’s desire to express his political views about the late 1960s, and by implication, the mid 80’s when the novella version was published. Gray, however, refuses to answer directly until the final paragraph where refutes Axelrod’s suggestion saying, ‘as to my political reasons for writing it — I had none at all’. It is difficult to believe that a writer who dedicated Working Legs (1997) – a play that explores disability and the social welfare system – to ‘Baroness Thatcher and all the right honourable humpty dipsies who have made our new, lean, fit, efficient Britain’, had no political reasons for writing Kelvin Walker. It is, after all, a fable written in the Thatcher years which casts aspersions on the imperial British centre.

McGrotty and Ludmilla, central image from Dog and Bone book jacket (1990), courtesy AGA

Although Gray’s response to Axelrod – ‘I had none at all’ – seems dubious, the explanation that follows it contextualises the writer’s point. By stating that ‘the politics of any story I tell are the politics of the country where I live’, Gray implies that expressing a personal political agenda is not foundational in his writing, but rather that place and politics are too enmeshed to separate. The point is resolute. Yet, at the same time, it appears to side step an important issue: that the narrative anyone chooses to tell of their country and its politics is highly subjective. In light of this, Gray’s reference to the Arthurian Legends appears to be counterintuitive: 'The prime minister and newspaper owner in Kelvin Walker were as necessary to it as King Arthur and Merlin to a medieval romance.' The loosely historical accounts of the Celtic Briton and King are filled with supernatural phenomena and questing beasts (sadly not anthropomorphic ones). The legends were characterised by the 12th century historian William of Malmesbury as ‘fond fables which the Britons were wont to tell’ (British Library, 2019). Gray's reference to King Arthur undercuts his argument by suggesting it is subjective account of British political history which is slanted towards his own robust political views. In other words it is a tales Gray is 'wont to tell'.

The discussion of Gray's politics sparked a (fictional) debate between myself, Rachel Loughran, the editor of Poor Things: a Novel Guide, and one of its valued contributors, Scott McNee. What follows is a record of a discussion between them that never took place. Loughran took the Gray-like liberty of adapting the former's research into a fictional interview. She thanks him for his permission to use his academic investigation to ‘reinforce a fiction’ (PT, frontmatter).

Interview: Scott McNee & Rachel Loughran

Loughran: Scott, what’s your take on Gray’s position in the final paragraph of his Kelvin Walker interview, that he had no political reasons for writing it?

McNee: Alasdair Gray essentially argues against disentangling a story from its politics.

Loughran: You mean his subjective stance on those politics?

McNee: Novels are not created in a recess from the author’s life.

Loughran: Can you give an example?

‘McNee’: Is this an interview or an exam?

Loughran: Neither. It’s a fabrication based on fact. I’m trying to make the dialogue flow. I’ll try and smooth out the rough edges in the edit. The reader will never know. Back to it. Can you give an example?

McNee: An extreme but apt example is that of Coleridge’s poem ‘Kubla Khan’, never completed, allegedly due to an ill-timed visit that disrupted the poet’s process.

Loughran: But what about Kelvin Walker? Gray’s novella wasn’t created by a disruption as Coleridge’s poem was(or so the story goes). Gray's novella was written because of an accumulation of circumstances: he reads J. P. Donleavy’s Fairy Tales of New York, he visits BBC London, he writes his screenplay in the swinging sixties and adapts it into a novella the mid 80s when Thatcher's neoliberalism is in full swing.

‘McNee’: You asked for an example. You got an example.

Loughran: I have to say, ‘Scott’ you are being uncharacteristically abrupt in this interview…

McNee: Gray lived all of his life in Glasgow; when writing Poor Things, a book that is primarily concerned with Victorian Glasgow and the wider British Empire, it is natural that it comes to reflect the contemporaneous Glasgow he inhabited and its political environment.

Loughran: Ok. Point taken. But when you say ‘natural’, a word that implies something inevitable or to is expected, don’t you mean ‘expected for someone like Gray who has a political agenda?' Gray takes a very deliberate political stance in his novels. Frequently his own political beliefs filter through his characters' mouths.

‘McNee’: Can you give us an example?

Loughran: Touché

‘McNee’: Back to it: can you give us an example?

Loughran: Well, for a start there’s Bella. After listening to the ‘bitter-wisdom’ of Harry Astley, who I might add, ventriloquises an ironic Gray on a range of Gray adjacent subjects including Education, History, War, Unemployment, Freedom, Free Trade, Empire and Self Government (pp. 155-63)), Bella’s logical conclusion is: ‘I must be a socialist’ (p164). We shouldn’t forget that before Godwin, Bella’s maker is Gray.

‘McNee’: Exactly.

Loughran: Huh?

McNee: Novels are not created in a recess from the author’s life.

Loughran: This again…

McNee: It’s no coincidence that the ‘manuscript’ of Poor Things is discovered in the litter that has come about from lack of government interest in history and art – Michael Donnelly discovers Archibald McCandless’ work in cast-off legal documents while scavenging for things that might be of interest to the People’s Palace (something Gray notes he is forced to do, due to a complete absence of council funding). Even here, access to knowledge is denied – the law office, despite being in the process of destroying the papers of the deceased forbid Donnelly from retrieving anything. Gray notes that the lawyer in question is also a ‘local politician’ who goes unnamed; Donnelly is forced to break the law to prevent the establishment from destroying its own history.

Loughran: Do you think the ‘local politician’ might be a reference to

‘McNee’: No comment.

Loughran: Go on!

‘McNee’: Please may I continue?

Loughran: Go on then…

McNee: Gray, in turn, comes into the possession of the manuscript, scavenging it from Donnelly after the social upheaval of Glasgow being named European City of Culture in 1990…

Loughran: For more on that take a pit stop to West End Park in Archie McCandless' Glasgow Tour!

McNee: (clears throat) Ahem.

Loughran: (graciously) Go on, please.

McNee: Gray comes into the possession of the manuscript, scavenging it from Donnelly after the social upheaval of Glasgow being named European City of Culture in 1990, which causes the latter to leave The People’s Palace. ‘It is here,’ Dietmar Böhnke writes, ‘that Gray’s concern with the “poor things” of society becomes again apparent. (Böhnke, 2004, p234).

Loughran: You mean the 'poor things' of Gray’s contemporaneous society?

McNee: As Böhnke states: one of the aims of the Workers’ City group, with which Gray was associated, was to show how very little Culture City would benefit the workers, the unemployed and the homeless.’ (Böhnke, 2004, p234).

Loughran: For more on that take a pit stop to West End Park in Archie McCandless' Glasgow Tour!

McNee: (clears throat menacingly) Ahhhem.

Loughran: (less graciously) Go on, please.

McNee: Long before we meet any of the fictional characters of Poor Things, these fictionalised versions of Gray and Donnelly are chiefly used to illustrate the absurdity of the political and cultural situation in 1990s Glasgow – the reader is led to believe that this contemporary setting is relevant to the Victorian society soon to be depicted. Gray’s posture as a literary executor is a fairly common device.

Loughran: Yes - Umberto Eco claiming to be adapting a translation of a genuine account in The Name of the Rose, for example.

‘McNee’: I wrote that.

Loughran: True. Ok, well another example would be Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Master of Ballantrae. Both Gray and Stevenson’s novels show fictional editors collating a variety of narratives. Each also contains unreliable narrators. In Poor Things, what appears to be the basic narrative (in McCandlesses’ Episodes) is given to the reader in a tone so pitched as to suggest that its speaker is an authoritative narrator in the book. The reader is told of this character's parentage, his life at university, his poverty, what he sees as his manly independence, and his friendship with Godwin Baxter. This impression of authenticity is initially confirmed by the method through which (imitating Stevenson) Alasdair Gray claims to be no more than the editor of these memoirs, in fact composed by a deceased public health officer.

‘McNee’: Philip Hobsbaum wrote that.

Loughran: True.

‘McNee’: And for more of that hit the image below!

REDACTED

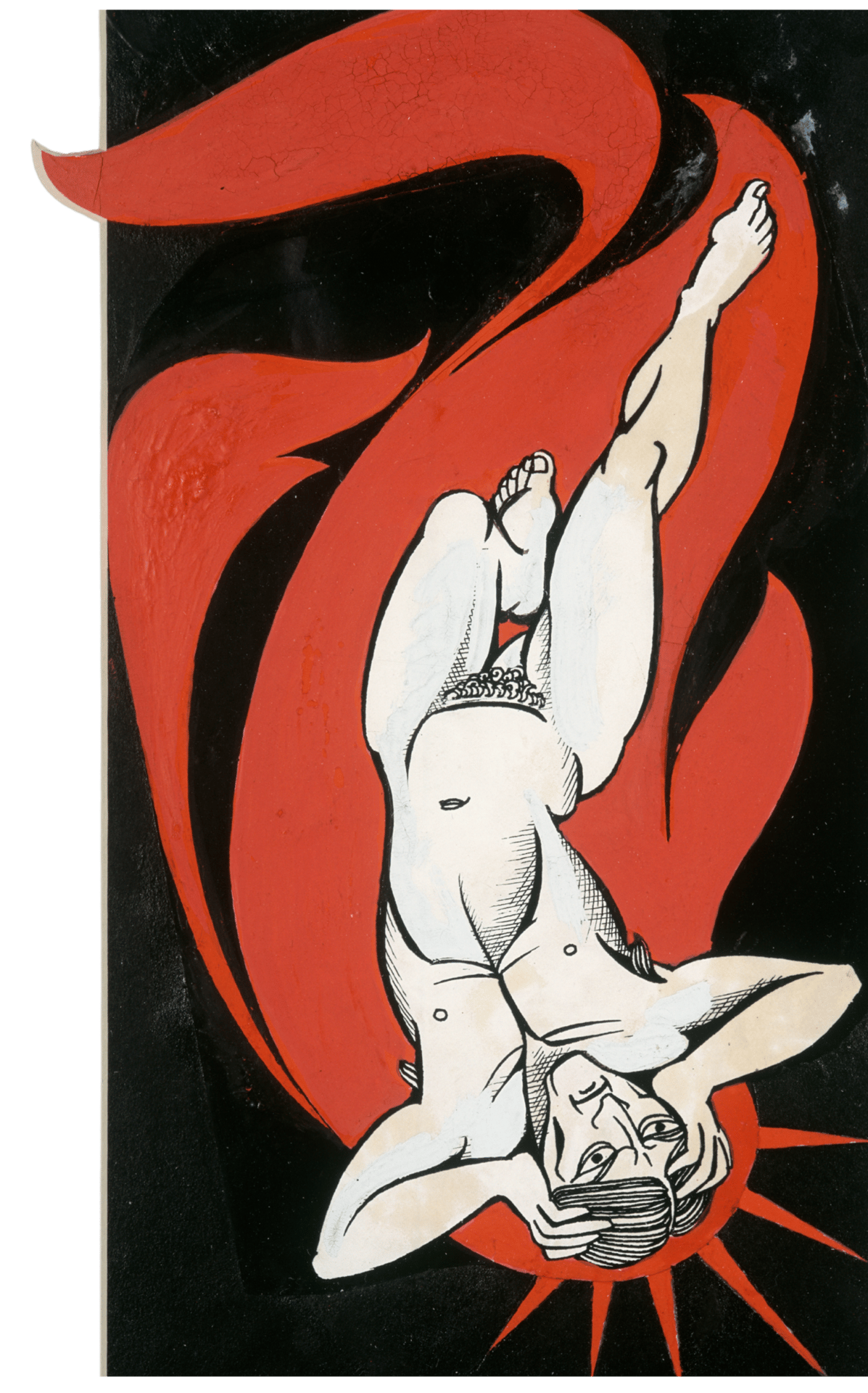

Symposium at Nightmare Abbey (1976-2005) was painted as a wedding gift for Philip Hobsbaum and his wife Rosemary. Philip is on the left with Byron on one side and Edward Irving on the other. Rosemary faces him between Shelley and Coleridge. Her daughters are outside the window.

To read Philip Hobsbaum's essay Unreliable Narrators: Poor Things and its Paradigms, click the image directly below. Scroll a little further to be met by Gray's monsterous doctor Godwin Baxter, who will guide you forward on your journey through Poor Things: a Novel Guide.

It's not too late to save yourself from the fall!! Click on the image to fly back up to safety!!

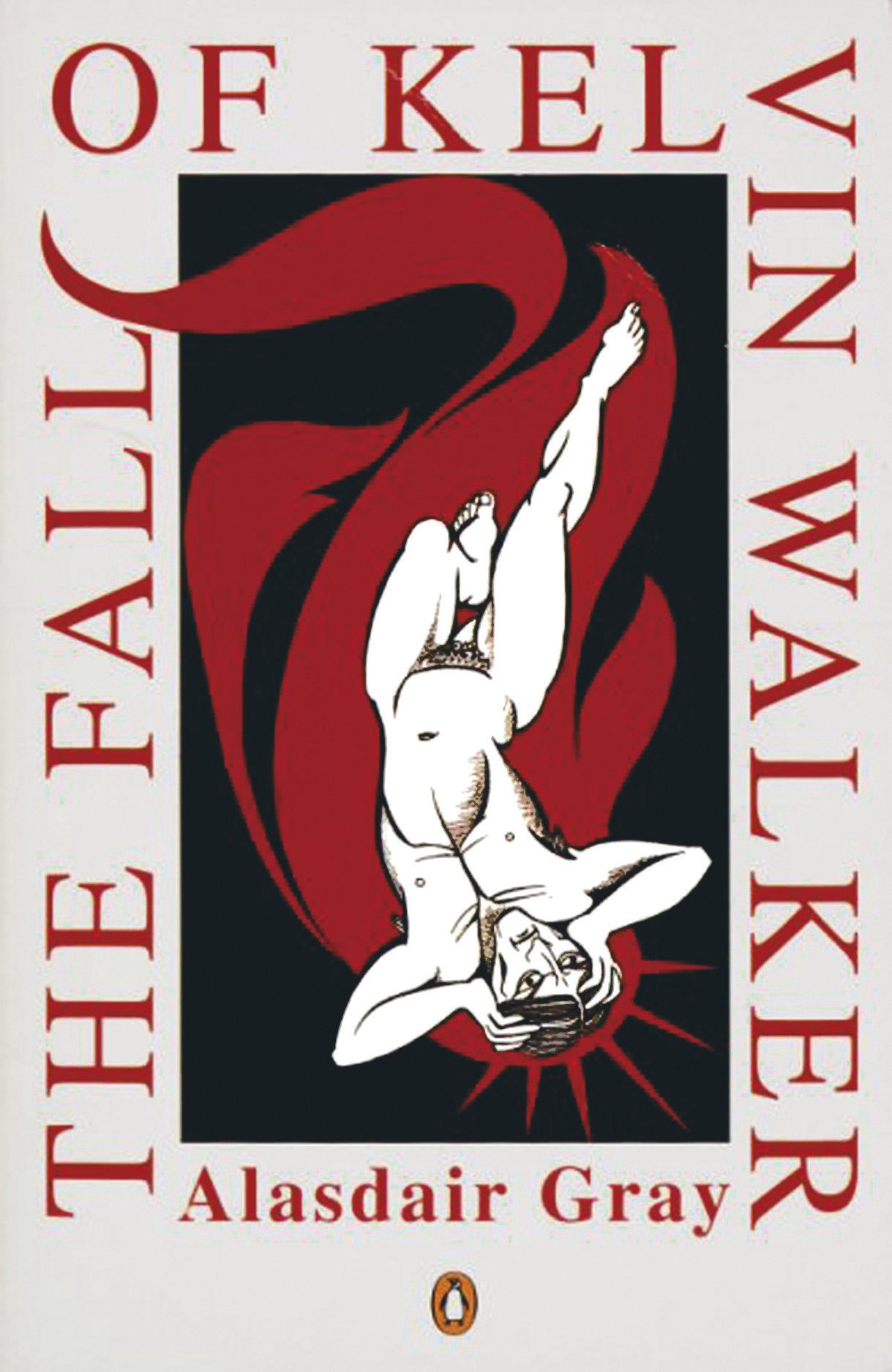

The Fall of Kelvin Walker, Cannongate book jacket central image (1985), courtesy AGA

The Fall of Kelvin Walker, Penguin book jacket (1985), courtesy AGA

*Alternatively you could have scrolled below the image of the friendly lookng man in the midst of falling into a bottomless perdition to read a useful commentary that the writer-editor of 'Gray-the-Editor' had carefully designed for you. To read it now, please click on the book jacket beside this text. Thanks in advance.