INTERTEXTUALITY

/ˌɪntəˌtɛkstjʊˈalɪti/

The relationship between texts, especially literary ones.

"every text is a product of intertextuality"

Allusion

noun

an implied or indirect reference to a person, event, or or other literary work with which the reader may be familiar

noun

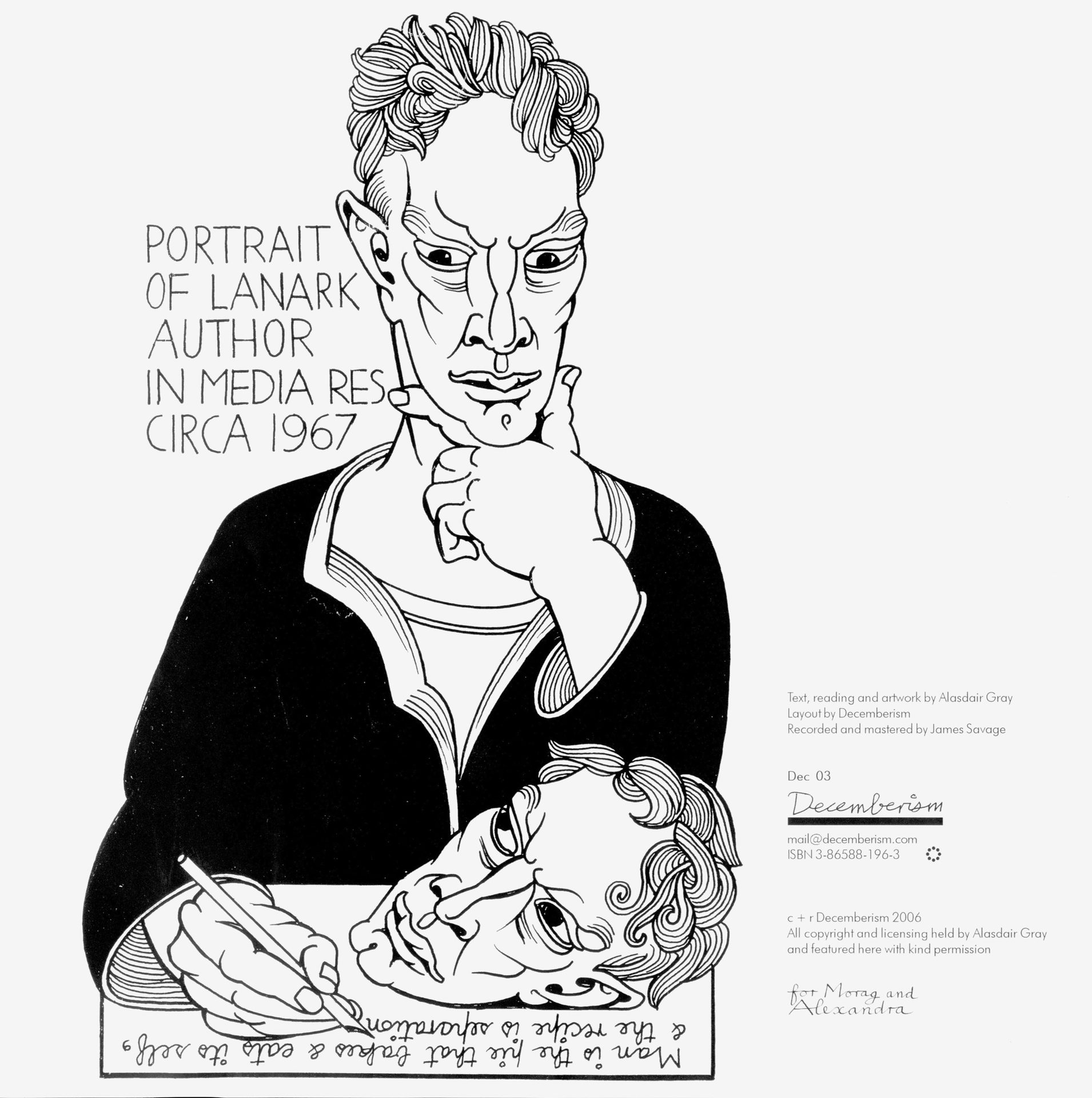

What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filched from? I find traces of The Coming Race, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dracula, Trilby, Rider Haggard’s She, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes and, alas, Alice Through the Looking-Glass; He has even plagiarized […] G.B. Shaw’s Pygmalion and […] Herbert George Wells (p273).

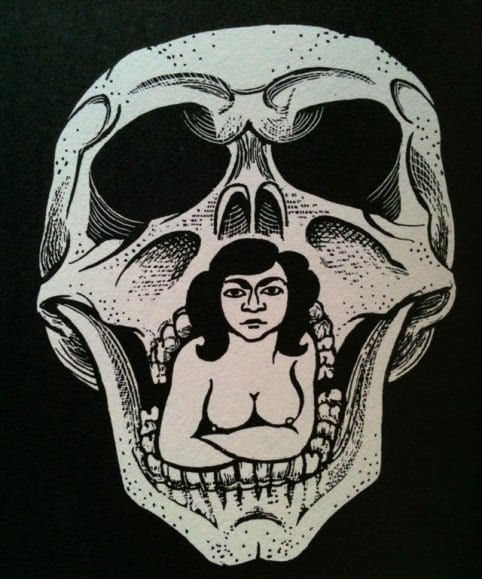

Poor Things (1992) illustration, courtesy AGA

I have collected enough material evidence to prove the McCandless story a complete tissue of facts (pXIV).

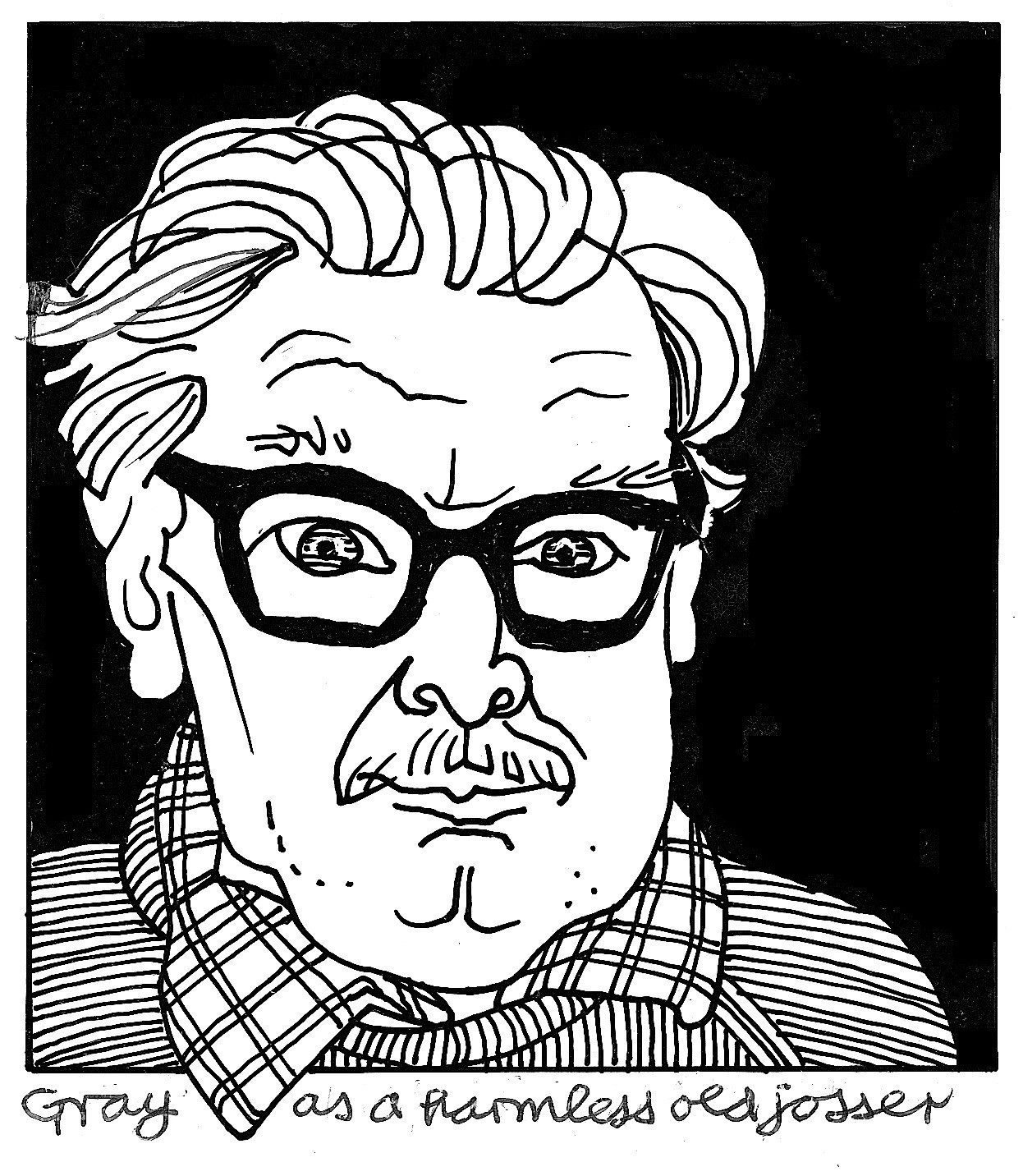

Gray as a Harmless old Josser (1990), courtesy AGA

To read an introduction to Gray's use of intertextuality within his written work and his creative practice, scroll below. To jump straight to the Poor Things Glossary of Intertexts click on the wee furry fella below. He'll guide you on your way.

Ten Tall Tales and True (1993) illustration, courtesy AGA

Introduction

Gray was a master of reusing images, ideas, quotations, and styles from other writers and artists. As Victoria McCandless reminds us, Gray (in the guise of her husband Archibald McCandless) makes use of a great number of source texts in Poor Things including 'traces of The Coming Race, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dracula, Trilby, Rider Haggard’s She, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes and [...] Alice Through the Looking-Glass' (p273). It is partly this intertextuality - the interconnectedness between different texts, where the meaning of one text is shaped by its relationship to other texts - that makes Gray's novel 'tissue-like' as Gray-the-editor prompts us to consider: 'I have collected enough material evidence to prove the McCandless story a complete tissue of facts' (pXIV). Besides something to blow your nose on, a tissue is, after all, 'an intricate structure or network made from a number of connected items' (OED). Poor Things is built upon an intricate structure through its intertextuality. Critic Neil Rhind highlights this when he states that the phrase 'tissue of facts' is intimately tied to intertextuality. '[It] echoes Roland Barthes [who states] "the text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture” (quoted in Bentley p46)'. Rhind continues 'for Bentley, “this produces a radical notion of a text as a multi-dimensional space made up of quotations from and allusions to other writings"' (Rhind, 2009, pp.24-5).

Gray's unique approach to alluding to the texts of others within his own work is in itself multi-dimensional, as Sorcha Dallas, custodian of The Alasdair Gray Archive explains in the video below.

Gray Tales, Erratum (with Scorcha Dallas) (2022), filmed by Kevin Cameron with thanks to Creative Scotland and D8, design by Neil McGuire, courtesy AGA

Note Critical

The Alasdair Gray Archive's Creative Commission series is when we invite a creative practitioners to respond to some element of Gray’s work, practice or approach, to produce something new that is meaningfully connected but also exists as a new work in its own right. Throughout his working life, Gray sought to celebrate and declare his influences, seeing them as an integral part of all making. Similarly, we encourage and support creatives to respond to Gray’s work, taking inspiration from it, but making new work of their own, that can stand alone and make it a generative resource. In 2023, as part of the The Made Project module, part of the MLitt in Creative Writing at Strathclyde, we commissioned the celebrated journalist and non fiction writer Chitra Ramaswamy to spend time at the Archive, choosing something to respond to. She wrote a whole series of micro essays called Rich Things. For this commission, Chitra highlighted the interwoven histories inspired by both the physical material within the archive and traces of which remain in the landscape outside. This brave series of essays question which histories are remembered and which are forgotten. Owning our collective history, being brave about telling the truth is crucial for us to learn, do better and collectively grow. Chitra performed a section of Rich Things at our Gray Day in 2023 at Oran Mor. She also delivered a workshop at the Archive for the MLitt in Creative Writing at Strathclyde students, discussing her own creative approach which acted as a case study for the students to then produce their own creative responses to texts, images and/or artefacts within the Archive. We are developing a project to deliver Rich Things as our first publication in 2024.

In her Creative Commission for The Alasdair Gray Archive, writer Chitra Ramaswamy reflects on how Gray 'made a new use out of old discarded things' within his literary work and his creative practice. Click the playbar below the 'note critical' to hear from Chitra.

Recording from Gray Day 2023 Live featuring Chitra Ramaswamy, 25 February, Òran Mór, Glasgow, courtesy AGA

Index of Intertexts

Below those rather delightful-looking bunnies, you'll find the Index of Intertexts. The Index, as you might have guessed, lists all the intertextual references, spied, plucked and compiled by the sharp-eyed literary detective, contributor Scott McNee. Each book title is listed in alphabetical order and is accompanied by the relevant citation from Poor Things in addition to commentary by McNee. I have to say, those bunnies are reminiscent of Lewis Carroll's White Rabbit. Don't you agree?

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland/Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There – Lewis Carroll (1865/1872)

‘I find traces of … alas, Alice Through the Looking Glass; a gloomier book than the sunlit Alice in Wonderland.’ (p273)

Victoria writes of the Alice novels being among the books provided by Godwin that first allowed her to enjoy reading. The parodic characters and farcical situations in both novels are not dissimilar to Gray’s treatment of both Victorian society and the present day.

‘The Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond’ – Anon (Round No.9598)

‘As Baxter unlocked his front door I thought I heard a piano playing The Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond so loud and fast that the tune was wildly cheerful. He led me into a drawing-room where I saw the music being made by a woman seated at a pianola.’ (p28)

Bella’s first appearance is marked by this popular folk song; its relative simplicity begins her education and her perceived rebirth from a Mancunian victim into an independent Scottish woman. Victoria’s letter misidentifies it as being written by Robert Burns.

The Brothers Karamazov – Fyodor Dostoevsky (1880)

‘This may not be much but it satisfies me, and is better than being a bed bug. Though of course, bed bugs too must have their unique visions of the world.’ (p123)

The Russian gambler Bella meets in Odessa references Dostoevsky’s works, which as Gray notes, have yet to be published in English at this time. In particular this quote appears to refer to the quote from The Brothers Karamazov that begins: ‘I am a bug, and I recognise in all humility that I cannot understand why the world is arranged as it is’. Dostoevsky frequently refers to ‘bugs’ ‘insects’ and ‘spiders’ across his works when considering existential questions. The gambler, by profession, resembles Dostoevsky himself.

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle (1927)

I find traces of… The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes…’ (p273)

Victoria accuses Archie of plagiarizing this final, lesser collection of Holmes stories. Godwin, eccentric genius and his average narrator companion Archie are reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson respectively

The Coming Race – Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1871)

‘I find traces of The Coming Race…’ (p273)

In this novel, the Vril-ya civilisation have equal rights among the sexes, and the women are both larger than the men and expected to be the romantic pursuer. Similarly, Bella is forward in sexual matters and proves to be ‘larger than the male’ in her career as Victoria, overshadowing her husband.

Companion Encyclopaedia of Medical History – edited by WF Bynum and Roy Porter (1991)

‘Our nurses are now the truest practitioners of the healing art. If every Scottish, Welsh and English doctor and surgeon dropped suddenly dead, eighty per cent of those admitted to our hospitals would recover if the nursing continued.’ (p17)

In his notes, Gray compares Godwin’s assessment with that of an entry by Johanna Geyer-Kordesch on Florence Nightingale and her methods (p280). Dr Victoria McCandless will eventually come to radically disagree with the male medical establishment.

The Company I’ve Kept – Hugh MacDiarmid (1966)

‘Until 1945 the house became one of several unofficial little arts centres flourishing on or near Sauchiehall Street. The painters Robert Colquhoun, Stanley Spencer and Jankel Adler briefly lodged in it or visited it. So did the poets Hamish Henderson, Sidney Graham and Christopher Murray Grieve, better known as Hugh MacDiarmid.’ (p315)

All of these figures are real, and Gray’s purported source is MacDiarmid’s (equally real) autobiography. The poet and author moved through various leftist and nationalist Scottish circles, reinforcing that Victoria remained politically active despite her would-be isolation.

The Divine Comedy – Dante Alighieri (1321)

‘[We] are taught to admire cruel killers like Achilles and Ulysses…’ (p155)

Astley’s negative perception of Achilles and Odysseus (and using the Latin name for the latter) implies familiarity with their depiction in Hell in Dante’s Inferno, as opposed to their more sympathetic portrayal in The Iliad. Gray would later go onto translate his own version of The Divine Comedy.

Dombey and Son – Charles Dickens (1846)

‘Dickens was writing Dombey and Son in 1846 when he heard about Blessington’s lethal Sandhurst prank.’ (p292)

Gray claims Dickens was influenced by (the fictional) Blessington’s brutality to parody military school in his novel. Dickens did have a habit of fictionalising real people and incidents.

Dracula – Bram Stoker (1897)

‘I find traces of… Dracula’ (p273)

Dracula is largely told through epistolary format – letters, transcripts and documents from various characters are assembled to tell the complete story, much as Poor Things is made of Archie’s manuscript, letters from Bella and Victoria, with editorial comment from Gray.

The Eagle (Fragment) – Alfred Lord Tennyson (1851)

‘Tennyson met [Blessington] at a public banquet in support of Governor Eyre and was so impressed that he wrote The Eagle. Though many people know it, few realize it is a romantic portrait of the author’s friend…’ (p291)

Tennyson was Poet Laureate for most of the Victorian Era. Like many artists appointed by politicians, his work is often seen as the voice of the status quo – in this case, of British Imperialism and militarism exemplified by Blessington.

An Essay on the Principle of Population – Thomas Robert Malthus (1798)

‘’Not quite faithless,” murmured Mr Astley. “I am a Malthusiast – I believe in the gospel according to Malthus.’ (p132)

The writings of Malthus advocate population control under the reasoning that resources (particularly food) are finite. Astley uses this to justify his mercenary sense of loyalty and cynicism, though as Bella discovers, this world view only makes him more depressed.

Frankenstein – Mary Shelley (1818)

‘…with additional ghouleries from the works of Mary Shelley’ (p272)

The general plot of the novel, the creation of life by a scientist, is reflected in Poor Things. Bella’s education in particular mirrors the Creature’s narrative at roughly the same point in both novels. Godwin Baxter resembles the giant scale of the Creature as much as he does Victor Frankenstein – certain descriptions of him evoke the popular image of Boris Karloff’s monster in James Whale’s film Frankenstein (1931)

Für Elise – Ludwig Van Beethoven (1867)

‘[My fingers] have ached playing Beethoven’s Für Elise nineteen times without stopping on the piano because my teacher made me start again whenever I hit the wrong note.’ (p262)

Victoria chafes against a standard young woman’s education in classical music – at odds with her love of Scottish folk song as Bella. Given her age, the piece had only recently discovered when she was a child.

Hamlet – William Shakespeare

‘Hoist with my own petard ha ha ha ha ha.’

When Wedder does not want to explain his funny words he gets out of it by using others.’ (p170)

Wedderburn has a tendency to speak in cultural references and dramatic language, both to show off and to avoid any personal admittance or responsibility. Notably Bella also begins her letters writing in this manner, until she finds her own voice and remarks ‘I will not write like Shakespeare anymore. It slows me down…’ (p115).

Kipling, Rudyard

‘But the finest poetic tribute to Blessington is by Rudyard Kipling, who believed the General had been hounded to his death by parliamentary criticism…’ (p291)

Gray parodies Kipling with ‘The End of the Thunderbolt’, purportedly written by the latter, a melodramatic slog of mythologising Blessington surrounded by imperialist racism. Kipling, most famous for The Jungle Book, has suffered a decline in reputation over the years due to his jingoist support for the British Empire and colonialism. Gray does not appear to have a high opinion of his writing.

Lanark: A Life in Four Books – Alasdair Gray (1981)

‘What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filched from?’ (p272)

Plagiarism is meant to be a harsh accusation coming from Victoria, but Gray cheerfully referred to all of his influences as ‘plagiarisms’, most famously in ‘Index of Plagiarisms’ in Lanark.

The Last Days of Pompeii – Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1834)

‘I know things were not always thus. I have read The Last Days of Pompeii, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Wuthering Heights so know that history is full of nastiness…’ (p134)

Bulwer-Lytton’s novel, set around the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, deals with characters of various nationalities struggling for their place within the Roman Empire – mirroring the nationalities contained within the British Empire in Poor Things.

Les Aventures de Télémaque, fils d'Ulysse – Francois Fénelon (1699)

‘[My head] has ached because I had to memorise passages of Fénelon’s Télémaque, surely the dullest book ever.’ (p262)

Fénelon’s addition to The Odyssey chronicles the education of Odysseus/Ulysses’ son Telemachus as a rather poor cover for Fénelon educating the grandson of Louis XIV of France. It is indeed exceedingly dull.

The Life of Samuel Johnson – James Boswell (1791)

‘I think it like Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson; a loving portrait of an astonishingly good, stout, intelligent, eccentric man recorded by a friend with a memory for dialogue.’ (pxiii)

An early classic among biographies. Gray is explicitly comparing Godwin and Archie to Johnson and Boswell respectively here. Gray was a noted fan of the book – on being pitched the similar Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography by Rodge Glass, he instructed Glass to ‘be my Boswell!’

Les Miserables – Victor Hugo (1862)

‘My best friend here, Toinette, is a Socialist, and we often talk about improving the world, especially for the miserable ones, as Victor Hugo calls them, though Toinette says Hugo’s special insights are tres sentimental and I should apply myself to the novels of Zola.’ (p181)

Hugo is well known for this novel focusing on the poor and downtrodden. His portrayal of abject poverty likely resounds with Bella’s recent experience in Alexandria. Toinette prefers the novels of the contemporaneous Emile Zola, which have similar concerns of social justice but are raunchier and less sentimental, as she notes.

The Modern Traveller – Hilaire Belloc (1898)

‘…Belloc’s caricature of an empire builder – Captain Blood – was based as much upon General Blessington as upon Cecil Rhodes…’ (p299)

Gray continues to use existing works to establish Blessington as a person of considerable fame and infamy. Belloc was a friend and contemporary of George Bernard Shaw (see below), so it is likely Victoria McCandless is familiar with him too.

Old Mortality – Walter Scott (1816)

‘He thinks it a blackly humorous fiction into which some real experiences have been cunningly woven, a book like Scott’s Old Mortality…’ (pxiii)

Michael Donnelly references this novel as a comparison point to Archie’s manuscript, suggesting that it is historical fiction.

On the Nature of Things – Lucretius (First century BC)

‘”In De Rerum Natura Lucretius tells us that only debauched females wiggle their hips.”

“Thar creed is both false to nature and false to most human experience.” (p218)

Godwin has a poor opinion of Classical Athenian misogyny and is baffled by its support among the Christian medical establishment represented here by Blessington and his doctor.

On the Origin of Species – Charles Darwin (1859)

‘He says cruelty to the helpless will never end because the healthy live by trampling these down. … He has given me books that prove this… : Malthus’ Essay on Population, Darwin’s Origin of Species and Winwood Reade’s Martyrdom of Man.’ (p152)

Like many Victorian men of the era, Astley has taken the evolutionary theory that nature is ‘red in tooth and claw’ and applied it to the contemporary social structure, usually called social Darwinism. It has little resemblance to Darwin’s scientific writing.

One Thousand and One Nights

‘I also discovered… The Arabian Nights (this last in a French translation which included the erotic passages).’ (p264)

The famous book of Middle Eastern folk and fairy tales. Victoria here draws attention to the proliferation of copies that excise any erotica, again highlighting the denial of sexual matters in Victorian polite society.

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner – James Hogg (1824)

‘He has made a sufficiently strange story stranger still by stirring into it episodes and phrases to be found in Hogg’s Suicide’s Grave…’ (p272)

Hogg’s novel (Victoria refers to it by its original title) is a classic Scottish Gothic – themes of doubling, apparitions and unreliable perception abound. Archie’s flowery drunken outbursts and Wedderburn’s mad letters are a pastiche of the frenzied narrators in Hogg’s Gothic stories. Archie notes his regret in raving ‘in the language of novels I knew to be trash’ (p37).

Poe, Edgar Allan

‘…with additional ghouleries from the works of Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe’ (p272)

The famous writer of American Gothic fiction. Many of his stories and poems deal with the figure of a young woman, either long lost or mistakenly pronounced dead haunting the narrator’s mind, most notably in ‘Berenice’, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ and ‘The Raven’. Bella is one of these women herself – at least by Victoria’s scathing assessment of the manuscript.

Punch

‘The pictures showed many kinds of people. The ugliest and most comical are Scots, Irish, foreign, poor, servants, rich folk who have been poor until very recently, small men, old unmarried women and Socialists.’ (p127)

A real satirical magazine, Punch lasted from 1841 to 1992. Gray’s inclusion of it here highlights that its comedy only serves to uphold the status quo.

Pushkin, Alexander Sergeyevich

‘Then Pushkin learned the folk-tales from his nursemaid, a woman of the people. His novellas and poems made us proud of our language and aware of our tragic past – our peculiar present – our enigmatic future. He made Russia a state of mind – made it real.’ (p116)

The Gambler, though unaware of it, is making the case for Bella Caledonia – she has left England for Scotland and is now associated with Scottish folk-song. Pushkin’s fairy tales, in collections such as The Bridegroom (1825) here make the case for a national identity among the people who spread such tales – no longer subjects but citizens.

Pygmalion – George Bernard Shaw

‘He has even plagiarised work by two very dear friends: G. B. Shaw’s Pygmalion… this infernal parody of my life’s story…’ (p273)

Popularly remembered as the source of My Fair Lady, Shaw’s play details the relationship between a gentleman and the woman he has ‘created’ by educating her on modern society. Victoria explicitly notices the comparison to her and Godwin, and emphasises this over the Frankenstein connection. Shaw was a member of the Fabian Society, which Victoria joins and later leaves over their perceived lack of action.

The Scots Kitchen – Marian McNeill (1929)

‘Movement turns… flour butter an egg and a tablespoon of milk into Abernathy biscuits.’ (p134)

In his notes, Gray complains that Bella’s recipe is inaccurate, missing heat and baking powder (p287). This book of traditional Scottish recipes once again associates Bella with Scottish folk history.

She – H Rider Haggard (1887)

‘I find traces of… Rider Haggard’s She…’ (p273)

An adventure novel involving Ayesha, the white queen of a lost kingdom in Africa: ‘She-who-must-be-obeyed’. The novel deals with Victorian colonialism and the role of women in positions of power or renkown – appropriate for Bella’s journey.

‘Sir Patrick Spens’ – Anon, Child Ballad No.58

‘A fine, fine woman, McCandless, who owes her life to these fingers of mine – these skeely, skeely fingers!’ (p27)

Gray’s in-character notes suggest Godwin is paraphrasing this folk song – one of the first associations of Bella’s life with Scottish folk tradition. The song, centred on sea travel and danger, can also be associated with Bella’s rebirth by water.

Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde – Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

‘I find traces of… Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde…’ (p273)

The classic novella is a famous example of Gothic doubling as the respectable Dr Jekyll becomes Mr Hyde to express his darker urges. Bella’s rebirth at the hands of Godwin is a more positive example – escaping from the constraints of sexist society to discover her own wants and desires.

Tales from Shakespeare – Charles and Mary Lamb (1807)

‘But I loved Shakespeare most. So I started reading him at home, starting with Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, then the plays themselves.’ (p264)

A simplified and sanitised collection of Shakespeare’s plays, intended for children. It took until 1838 for Mary Lamb to be properly credited as co-writer, another example of women in the novel denied agency.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit – Beatrix Potter (1902)

‘…kiss Mopsy and Flopsy for me’ (p189)

Mopsy and Flopsy are most recognisable as the sisters of Peter Rabbit, though it is yet to be written by the time Godwin names his own rabbits.

Trilby – George du Maurier (1895)

‘I find traces of… Trilby’ (p273)

This popular Parisian novel parallels both Bella’s time there and her status as a woman desired by nearly every male member of the cast. The antagonist Svengali, a devious hypnotist and seducer, is alluded to in Wedderburn’s more outlandish accusations against Godwin and Bella.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin – Harriet Beecher Stowe (1852)

‘I know things were not always thus. I have read The Last Days of Pompeii, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Wuthering Heights so know that history is full of nastiness…’ (p134)

Stowe, a white abolitionist, centres this novel around the Black slave Uncle Tom. At the time it was popular among abolitionists for its anti-slavery bent in the lead up to the US Civil War. Now it is largely known for perpetuating condescending racist images of Black people.

Wagner, Richard

‘”Even Germans, who are racially closest to us, have a taste for brutally violent orchestral music and sabre duels.”’ (p140)

This is reference to Wagner’s bombastic Ring Cycle operas, of which Dr Hooker is evidently not a fan. Wagner’s operas were popular among the Nazis for their romantic portrayal of national myth and anti-Semitic stereotypes – considering Hooker is a racist phrenology enthusiast, it is somewhat ironic he does not like what will become the sound of his beliefs reflected in national policy.

The War in the Air – HG Wells (1908)

‘HG’s book is a warning of course, not a prediction. He and I and many others expect a better future because we are actively creating it.’ (p275)

Victoria McCandless is personal friends with (and possibly a lover of) socialist author HG Wells. She tragically hopes, pre-world wars, that the destruction of the novel will never come to pass. The fictionalised Gray notes the Glaswegian connection in his notes. The villain of the novel, militant German Prince Karl Albert, somewhat resembles General Blessington in reputation. Victoria accuses Archie of plagiarising Wells in her letter.

The Wealth of Nations – Adam Smith (1776)

‘To our right you will see railway yards and warehouses on the ground of the old university: the university where Adam Smith devised his world-famous treatise on the Wealth of Nations and his universally neglected one on social sympathy.’ (p196)

Godwin laments that what has lasted of Smith in the public eye is his clinical foundation for modern capitalism and not his empathetic work. The neglect of common humanity is a constant theme in Poor Things.

Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte

‘I know things were not always thus. I have read The Last Days of Pompeii, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Wuthering Heights so know that history is full of nastiness…’ (p134)

One of the most notable texts of Gothic literature, Wuthering Heights charts the violent generational struggle in a claustrophobic environment on the Yorkshire moors. The incestuous nature of the conflict is similar to that of Godwin’s initial intentions for Bella (at least, according to Archie). Bella explicitly compares Godwin to a maddening Heathcliff. Victoria McCandless at the end of the novel, an isolated strong-willed woman surrounded by dogs, somewhat resembles Emily Bronte herself.

Images in order of appearence: Poor Things, illustration portraying Victoria McCandless (1992); Gray as a Harmless Old Josser (1990); Every Short Story by Alasdair Gray 1951-2012, illustration (2012); Ten Tall Tales and True, pictorial initial capital B (1993); Ten Tall Tales and True, pictorial initial capital C (1993); Something Leather, Initial capital D portraying Morag McAlpine (1990); Ten Tall Tales and True (1993), pictorial initial capital E; Anatomy Museum sketch (1954); Something Leather, Initial capital H (1990); A Charm Against Serpents (1962); Lanark, title page (2014); Ten Tall Tales and True, pictorial initial capital M (1993); Something Leather, Initial capital O portraying John Purser (1990); Something Leather, Initial capital P portraying Bethsy Gray (1990); Something Leather, Initial capital S portraying Anita Manning (1990); Ten Tall Tales and True, pictorial initial capital T (1993); Every Short Story by Alasdair Gray 1951-2012, illustration (2012); A Scent of Water by Carl MacDougall, Pictorial initial W (1975); courtesy AGA