Synopsis

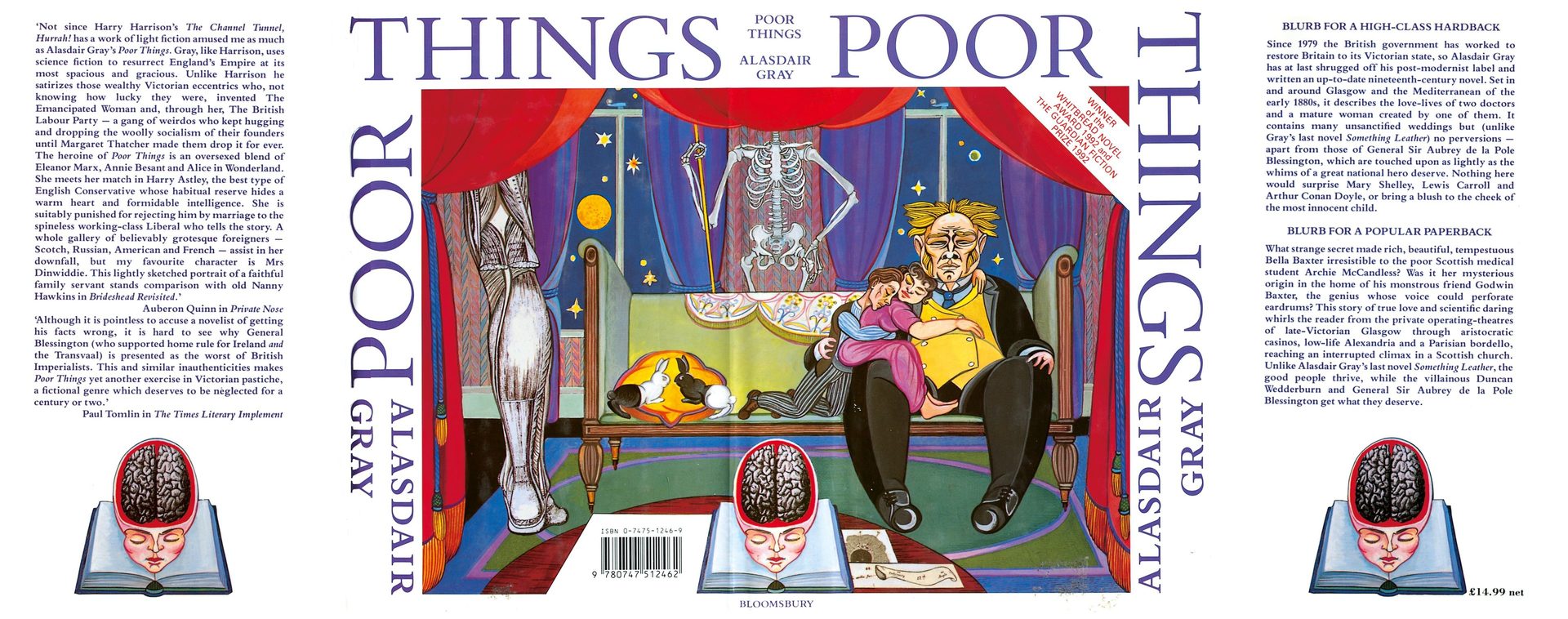

Poor Things (1992) book jacket (framed), courtesy AGA

Let's start at the start. Pick up your copy of Poor Things. What's the first thing you see?

The Book Jacket

You read POOR THINGS POOR THINGS [by] Alasdair Gray printed around the book jacket in purple lettering. In later editions the title text is accompanied by ‘Winner of the Whitbread Novel Award and the Guardian Fiction Prize’.

You notice a gigantic man with what looks like two sweet weans coorie-ing into his ample belly. Sweet, eh? Sort of. We later find out the weans are actually lovers Archibald McCandless and Bella Baxter. The latter was created by the big fella, Godwin Baxter, from the dead body of Victoria McCandless and the foetus of her unborn child. And why, you ask? To be his lover. And is that a skeleton on the spine? Yes. It is. In Gray's A Life in Pictures (2010), the artist and writer notes 'the flayed hand and leg were cut out of Gray's Anatomy, first published in 1858 and required reading by Victorian medical students. I bought two cheap reprints in a Byres Road remaindered book shop and used its splendid woodcuts (more distinct than any photograph) to complete the book's period flavour by filling empty space on introductory pages and chapter endings' (Life in Pictures, Gray, p242).

The first page of the book's front matter is a dedication. It is hardly unusual for a novel to begin with a dedication. However, Gray's attention to honouring those whose works and words influenced him goes beyond that of most dedications. This is not out of character for the novel's writer. For Gray, any input or inspiration that he received from others - be it large or small, deliberate or unintentional - was treated as a form of collaboration. Those who influenced his work were consequently treated as collaborators; their contributions were often recorded in text and image. In Gray's Òran Mór mural (2004), for example, eight framed panels depict the names and faces of the staff members who worked in the venue the year Gray painted it. In the writer's The Book of Prefaces (2000) each contributor, including the book's typist, typesetter, researcher, publisher and sponsor, is given their own portrait, their name inscribed under it. You'll find out more about several of the people and texts Gray's references in his dedication as you work your way through this novel guide. These include Bernard MacLaverty whose input was influential in the making of the novel and an epigraph by Dennis Lee that hides under the book jacket as well as the influence of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818). At the top of this paragraph you read that ‘it is hardly unusual for a novel to begin with a dedication’. That is still true. It is, however, somewhat strange for this novel to begin with such an open and honest account of Poor Things’ genesis, its influences and source texts. It is, after all, a fiction that tries hard to persuade you that it's not a fiction at all... The novel's dedication is printed in full below.

Front Matter: Dedications

'The author thanks Bernard Maclaverty for hearing the book as it was written and giving ideas that helped it grow; and Scott Pearson for typing and research into period detail; and Dr. Bruce Charlton for correcting the medical parts; and Angela Mullane for correcting the legal parts; and Archie Hind for insights (mainly from his play The Sugarolly Story) into the corrupted high noon of Glasgow’s industrial period; and Michael Roschlau for the gift of Lessing’s Nathan the Wise (published in 1894 by MacLehose & Son, Glasgow, for the translator William Jacks, illustrated with etchings by William Strang) which suggested the form (not content) of the McCandless volume; and Elspeth King and Michael Donnelley, now of the Abbot House local history museum in Dunfermline, for permission to use some of their earlier circumstances to reinforce a fiction. The shocking incident described by Bella in Chapter 17 was suggested by the Epilogue of In a Free State by V.S Naipaul. Other ideas were got from Ariel Like a Harpy, Christopher Small’s study of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and from Liz Lochhead’s Blood and Ice, a play on the same subject. Three sentences from a letter to Sartre by Simone de Beauvoir, embedded in the third and fourth paragraphs of Chapter 18, are taken from Quentin Hoare’s translation of her letters published by Hutchinson in 1991. A historical note on Chapter 2 is extracted from Johanna Geyer-Kordesch’s entry “Women and Medicine”, in the Encyclopaedia of Medical History edited by W.F. Bynum. The epigraph on the [hardback] covers is from a poem by Dennis Leigh [sic]. The author thanks a close friend for a money loan which allowed him to finish the book without interruption. '

The second page of the book's front matter is host to a short list of reviews. They say various complimentary things about Gray’s capacity to ‘contrast the political and moral bleakness of contemporary Britain with the civic energy that characterised the best of Victorian values’. Luckily it's still ‘witty and delightfully written’ (New York Times Book Review). Sounds good! Let's give it a go!

Front Matter: Reviews

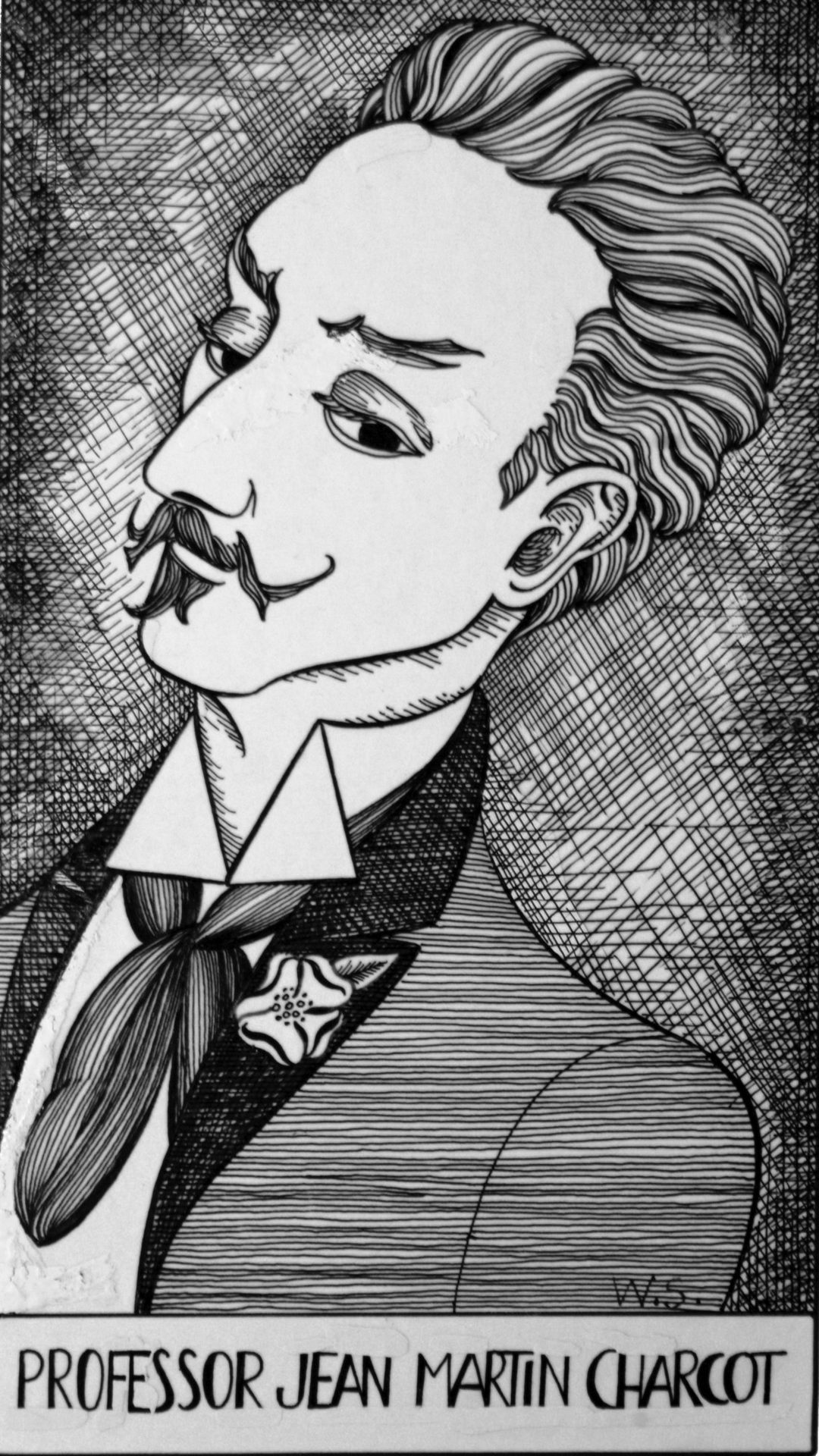

Wait more reviews? Some of these sound a bit dicier: ‘[Gray] has loaded his novel with false historical references and larded it with his own gruesome drawings’. And wait, there’s an erratum slip printed onto the page: ‘The etching on page 187 does nor potray Professor Jean Martin Charcot, but Count Robert de Montesquiou- Fezensac. Hang on – why is an erratum slip PRINTED on the page? Surely, it would be inserted into the text after it was published to mark any errors noticed following its publication? Hmm. And who is Professor Jean Martin Charcot anyway? And that Fezensac bloke. Are they both ‘false historical references?’ or real life historical figures? Better give that one a Google…

Front Matter: More Reviews

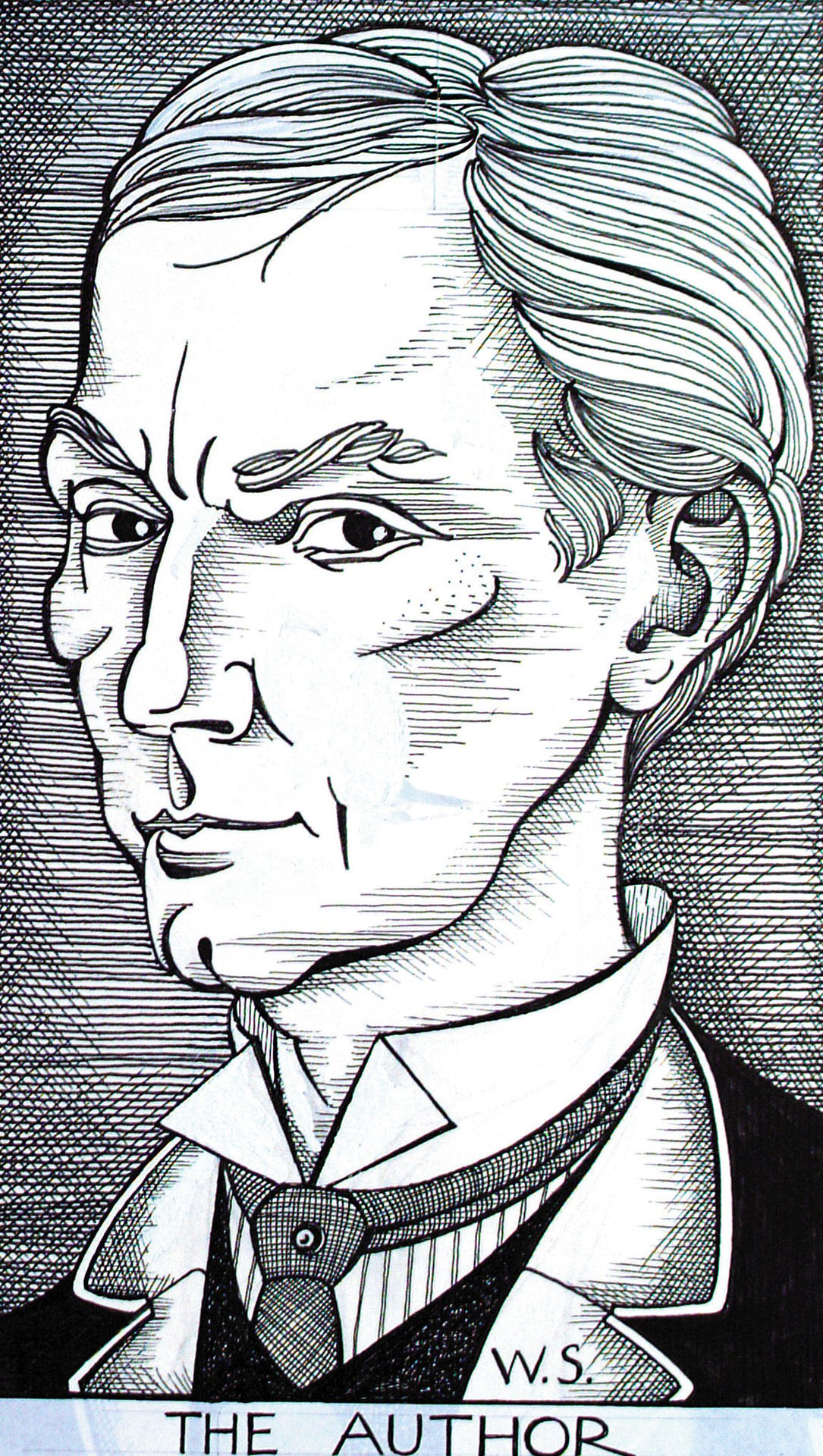

Poor Things (1992), illustration, courtesy AGA

Oh, there’s two biographies.

'Dr Archibald McCandless (1862-1911) was born in Whauphill, Galloway…he studied medicine at Glasgow University…’ But isn’t Alasdair Gray the writer of this book? Why has this McCandless fellow been given an author biography?? You skim read to the end: ‘his wife suppressed the first edition of his greatest work, Poor Things. Recently rediscovered by the Glasgow local Historian, Michael Donnelly…’

You jump to the next block of text:

‘Alasdair Gray, the editor, was born in Riddrie, Glasgow, 1934…’ Alasdair Gray THE EDITOR??!! But didn't he write the book?! Well, now I don’t know what to believe.

Front Matter: Author Biography

Is that McCandless’ wife? The one who suppressed the book? Or is that Alasdair Gray-the-Editor’s wife? Or wait, is that Alasdair Gray's wife?? I guess we'll find out...

Front Matter: Dedication

FOR MY WIFE

MORAG

The first thing we read is that Poor Things is a non-fiction work written by a 19th century doctor whose ‘surgical genius’ pal used ‘human remains to create a twenty-five-year-old woman’. Right. Well, that sounds plausible. Next, we read that Gray thinks McCandless’ account is true whereas local historian Michael Donnelly thinks it’s a load of old rubbish. We then read more about Michael Donnelly’s discovery of the Poor Things manuscript. He finds it in a bundle of documents that he then pilfers on his tea break at Glasgow’s local history museum The People’s Palace. The manuscript was placed inside a 'sealed packet with these words in faded brown ink: 'Estate of Victoria McCandless M.D. / For the attention of her eldest grandchild or surviving descendent after August 1974 / Not to be opened earlier’ (pX). Alongside it is a letter dated 1974 from Victoria McCandless. There's also a book, ‘EPISODES FROM THE EARLY LIFE OF A SCOTTISH PUBLIC HEALTH OFFICER / Archibald McCandless M.D. / Etchings by William Strang / GLASGOW: Published for the Author by ROBERT MACLEHOSE & COMPANY Printers to the University 1909’. Oh right, so all the illustrations are by Robert Strang after all? Or is Gray trying to hoodwink us?

Introduction

Poor Things (1992) illustration, courtesy AGA

Oh, just one more thing on the introduction. You should probably read this. It's written by Gray-the-Editor (Alasdair Gray's fictional persona).

'After six months of research among the archives of Glasgow University, the Mitchell Library’s Old Glasgow Room, the Scottish National Library, Register House in Edinburgh, Somerset House in London and the National Newspaper Archive of the British Library at Colindale I have collected enough material evidence to prove the McCandless story a complete tissue of facts. I give some of this evidence at the end of the book but most of it here and now. Readers who want nothing but a good story plainly told should go at once to the main part of the book. Professional doubters may enjoy it more after first scanning this table of events.

29 AUGUST, 1879: Archibald McCandless enrols as a medical student in Glasgow University, where Godwin Baxter (son of the famous surgeon and himself a practising surgeon) is an assistant in the anatomy department.

18 FEBRUARY, 1881: The body of a pregnant woman is recovered from the Clyde. The police surgeon, Godwin Baxter (whose home is 18 Park Circus) certifies death by drowning, and describes her as “about 25 years old, 5 feet 10¾ inches tall, dark brown curling hair, blue eyes, fair complexion and hands unused to rough work; well dressed.” The body is advertised but not claimed.

29 JUNE, 1882: At sunset an extraordinary noise was heard throughout most of the Clyde basin, and though widely discussed in the local press during the following fortnight, no satisfactory explanation was ever found for it.

13 DECEMBER, 1883: Duncan Wedderburn, solicitor, normally resident in his mother’s home at 41 Aytoun Street, Pollokshields, is committed to the Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum as incurably insane. Here follows a report from The Glasgow Herald, two days later: “Last Saturday afternoon members of the public complained to the police that one of the orators in the open forum on Glasgow Green was using indecent language. The constable investigating found the speaker, a respectably dressed man in his late twenties, was making slanderous statements about a respected and philanthropic member of the Glasgow medical profession, mingling them with obscenities and quotations from the Bible. When warned to desist the orator redoubled his obscenities and was taken with great difficulty to Albion Street police office, where a doctor pronounced him fit to be detained, but not to plead. Our correspondent tells us he is a civil lawyer of good family. No charges are being pressed.”

27 DECEMBER, 1883: General Sir Aubrey de la Pole Blessington, once nicknamed “Thunderbolt” Blessington but now Liberal M.P. for Manchester North, dies by his own hand in the gun-room of Hogsnorton, his country house at Loamshire Downs. Neither obituaries nor accounts of the funeral mention his widow, though he had married twenty-four-year-old Victoria Hattersley three years earlier, and neither her legal separation from him nor her death were ever recorded.

10 JANUARY, 1884: By special licence a civil marriage contract is signed between Archibald McCandless, house doctor in Glasgow Royal Infirmary, and Bella Baxter, spinster, of the Barony Parish. The witnesses are Godwin Baxter, Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, and Ishbel Dinwiddie, housekeeper. The bride, the groom and both witnesses are all residents of 18 Park Circus, where the marriage takes place.

16 APRIL 1884: Godwin Baxter dies at 18 Park Circus of what Archibald McCandless M.D. (who signs the death certificate) describes as “a cerebral and cardiac seizure provoked by hereditary neural, respiratory and alimentary dysfunction”. The Glasgow Herald, reporting on the burial service in the Necropolis, mentions “the uniquely shaped coffin”, and that the deceased has left his entire estate to Dr. and Mrs. McCandless.

2 SEPTEMBER, 1886: The woman who married Archibald McCandless M.D. under the name Bella Baxter, enrols in the Sophia Jex-Blake School of Medicine for Women under the name Victoria McCandless.' p XIII - XIV

Poor Things (1992) frontmatter, courtesy AGA

Poor Things (1992) illustrations; illustrations from Grey's Anatomy (1858) printed in Poor Things, courtesy AGA

Chapter Summaries

In the guide below you'll chapter summaries with !!!CORRECTIONS!!! from English teacher Peter McNally. Trust the English teacher to get out the old red marking pen.

1

Making Me

We get a short history of McCandless’ early life and acceptance to Glasgow University Medical school in 1879. And when I say short, I mean one and a half pages.

2

Making Godwin Baxter

McCandless and Godwin meet. We hear a brief history of Godwin’s life (less brief than McCandless'). Conversation about social inequity within the period’s medical institutions ensues. There will be much of this - in this digital guide and in the novel. If you want to find out more head to the Hunterian Anatomy Lab.

3

The Quarrel

McCandless asks Godwin ‘the exact nature of his researches’ (p19). The answer sounds pretty dodgy to me. It's worth reading I assure you. McCandless gets spooked by this and Godwin’s weird hands. They quarrel and part ways. Oh, and it’s also worth noting that Gray-the-Editor scrubbed McCandless’ chapter titles and made up his own, or so he tells us on page XIII of the introduction.

Good additional context, but you haven’t mentioned anything about the setting: Victorian Glasgow. Please read the following notes: It would be impossible to mention setting in a Gray novel without referring to Duncan Thaw’s wisdom that ‘if a city hasn’t been imagined by an artist then not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively’ (Lanark, Gray, 1981, p243). Poor Things takes this and runs with it. The images in Notes Historical and Critical show us Glasgow Green (with its faux gothic gates), Park Circus, Kelvingrove Park, the Landsdowne Church on Great Western Road and finally the Necropolis. Gray lets Archie paint it as a smoky, romantic place that could have housed Frankenstein or Jekyll and Hyde or Justified Sinner or Jane Eyre. He lets Victoria show us the slums and deprivation and need for more state intervention. Gray indulges his imagination and skill by painting pictures of Paris and Odessa in words and other impossibly romantic places. But Glasgow is the star of the show.

4

A Fascinating Stranger

We meet Bella Baxter for the first time. Bella meets McCandless for the first time. McCandless meets Bella for the first time. They’re both smitten. So are we.

I think this needs a little padding out. Don’t forget that Bella is a Frankenstein’s monster of a character. Literally. Or maybe. We have to suspend our belief at her creation (she jumps off a bridge into the Clyde and is an aristocrat from Manchester or what about the South American connection?) There seems to be consensus on Bella’s Early Years: Born in Manchester; married General Blessington; escapes to Glasgow and to Godwin. What the scars are from is up to you to decide. But we can’t help but be swept along with her. We relate. The realism is deep. She has to suffer fools. Who is worse? Archie, Godwin or her lover Duncan Wedderburn? Then we have her letter – is it her letter? – either way it takes us on a whistle stop tour of an old Europe of swish cafés and stone buildings (with some Parisian bordellos thrown in for fun). Before embarking on this journey she is presented by McCandless/Gray as naïve and childlike, but she changes rapidly and emerges as a pragmatic, intelligent keeper of the fools around her. But then we get Victoria account of things in her letter, where she jibes at Archie calling him a ‘poor fool’ (p251) and bemoans incompetence as a writer ‘why did he not make it more convincing?’ (p274) . And then we get Gray-the-editor putting that into question in Notes. Who is Bella!?

5

Making Bella Baxter

We find out more about Bella’s origins and (re)creation

Please see my comment above on 'padding out' your answer.

6

Baxter's Dream

‘My daydream of becoming a kindly popular beloved healer proved impossible’ states Godwin to a sympathetic Archie (p40). The giant doctor also mentions having a ‘woman shaped emptiness [in his life] that ached to be filled’. Put two and two together and is becomes evident that the woman Godwin designed to fill that emptiness is Bella. Oh, and then casually mentions that Bella’s brain is that of her unborn foetus. It is this that accounts for her childlike brain function Godwin explains. The chapter ends with Godwin telling McCandless:

But you need not believe this

if it disturbs you

(p42).

Well, it disturbed me alright.

7

By the Fountain

15 months pass. Bella makes a pass at McCandless. She has a mental age of 10 (p59). They get engaged the same day. Baxter wails. Ears are perforated. Was his 15-month world tour with Bella a fool’s errand? Did he prime and educate her to be the woman of his (day)dreams for only for McCandless’ to benefit? Was making Bella Baxter a mistake?

Good questions. On your next draft you could try and answer some of them. It is also worth thinking about the title of the chapter ‘By the Fountain’ and how it relates to one of the novel’s chief symbols: The Loch Katherine Memorial Fountain. This, of course, relates to Gray’s comparison between Victorian Glasgow and Glasgow in the 20th century. In Poor Things The Victorians are parodied, praised and puzzled. They are the perfect vehicle for Gray to go on a political polemic and force us to have a right good look at ourselves. Victorian high mindedness through architecture and public planning is admired. But we can also laugh at their silliness and stuffy fixed mindsets. We can’t laugh too hard though. Victoria tells us about her adult sons dying in the Great War and the novel ends. In her letter she mentions the hope that sprang from the Labour election win post WWII. Don’t forget that Gray is writing his novel in the midst of Thatcherism… We can laugh or appreciate all that’s gone before us, but perhaps we should also question our sense of human improvement.

8

The Engagement

Baxter separates McCandless and Bella to give her time to mature before they marry. Terrible love poetry is written. Whatever McCandless is, he’s no poet, that’s for sure. Bella also turns her hand to writing. Her infantile diction (p56) reveals her mental age (and unconventional relationship priorities):

DR CNDL,

Y WNY GT MCH FRM M THS WY. WRDS DNT SM RL 2 M WHN NT SPKN R HRD. YR LTTRS R VRY LK THR MNS LV LTTRS, SPCLLY DNCN WDDRBRNS.

YRS FTHFLLY,

BLL BXTR

For those of you unfamiliar with Bella’s terse prose it reads: ‘Dear Candle' (her punning nickname for McCandless, funny girl). 'You won’t get much from me this week. Words don’t seem real to me, when not spoken are hard. Your letters are very like other men’s love letters, especially Duncan Wedderburn's. Yours Faithfully, Bella Baxter’ (translation, mine).

Much of the humour of the novel comes from ‘Ding Dong Bell’'s spirted approach to intimate relationships and her unabashed sense of sexual autonomy (p189). It is humour that McCandless appreciates little, especially when Godwin reveals the meaning of the letter: that Bella is due to elope with ‘lecherous lawyer’ Duncan Wedderburn (p57).

9

At the Window

Bella alleviates McCandless concerns about their engagement by assuring him she’s only temporality eloping: she intends to grow into womanhood travelling around the world with Wedderburn. She declares that will marry Candle on her return. McCandless is assured. She chloroforms him and oot the windie she flies.

Have you considered the symbolic significance of ‘the journey’ Bella embarks upon? Bella and Duncan’s grand tour through belle époque Europe is almost a bildungsroman journey as we see Bella go from aspiring but hopeless poet to an empathetic and compassionate public spirited intellectual.

10

Without Bella

The men mourn the loss of Bella. McCandless moves into 18 Park Circus.

11

Eighteen Park Circus

The men continue to mourn the loss of Bella. They remain in 18 Park Circus waiting for her letters.

Could do better here.I think you’re being a bit glib about 18 Park Circus: a large chunk of the action takes place here. The smell of Godwin’s ‘dinners’ pervade and the large harem of dogs must have made it a pungent place to be. With its private operating rooms, rag tag interconnected bunch of servants (including Godwin’s mother) and domineering view from its ivory tower over the rest of the city, this is a place of learning and improvement that is trying to drag the rest of the city along with it.

12

Wedderburn's Letter: Making a Maniac

Whereas Bella’s journey takes her from an aspiring but hopeless poet to an empathetic and compassionate public spirited intellectual, as Wedderburn’s letter reveals, it takes him on a path towards mental collapse (and Catholicism). Coincidence? Agnostic Gray seems to be having a wee go at organised religion… Aside from Wedderburn’s letter being chock full of sexist slurs against Bella, it is a fine example of Gray's skilful manipulation of typography. (To find out more about that, follow Wedderburn by clicking on his image in the Character Gallery.) In chapter 12 we discover that Bella was recognised as being Victoria Blessington by a 'stout, stately, well-dressed woman who states: "how astonishing to see you Lady Blessington, when did you arrive? [...] Do you not remember me? Surely we were introduced four years ago at Cowes, on board the Prince of Wales' yatch?' (p88). Bella does not remember her. Owing to Godwin's lies, Bella believes herself to have been in Argentina four years ago - where her family was dessimated in a fatal train crash, where she escapes with only her memory lost.

Good comparison and context on Gray’s use of typography Rachel, but you haven’t mentioned a primary reason why Wedderburn descends into madness: Bella’s voracious sexual demands. See my notes on cuddles, candles and weddings: The novel is full of puns, wordplay and literary allusions. Some are very intellectual and noble, some are interesting puzzles to be decoded and some are just too sweet. Bella’s ‘weddings’ to Wedderburn every night (probably morning and noon too) during their journey highlight her curiosity, sense of fun and growing intellectualism. That Victoria uses the phrase too is a little clue to the truth of the matter, and a nice reminder that this creation (one that Gray was reportedly challenged into making by Kathy Acker given his previous portrayals of female characters) is one of the most memorable in all Scottish literature.

13

Intermission

McCandless and Godwin discuss Wedderburn’s letter before reading Bella’s version of events in a letter she sends them. A brief conversation about the limits of human knowledge occurs. The following citation can be taken as representative:

‘Our whole lives are a struggle with mysteries. Mysteries endanger us, support us, destroy us. Our great scientists have cleared away these mysteries in some directions by deepening them in others. The second-law of thermos proves the universe will end by turning into cold porridge, but nobody knows how it began, if it began’ (p100).

Classic Gray: when you think you’re getting a natter between two pals about their other pal’s holiday japes you get epistemology, thermodynamics with a big dollop of Scottish humour thrown in (also known as porridge).

Bella Baxter's Letter: Making a Conscience

Bella’s letter is split across chapters 14-18. Each covers a new location on her journey with (and without) Wedderburn. The letter is read aloud by Baxter who adds his own editorial flare by omitting certain sections along the way. It’s also worth remembering that although the letter is ‘handwritten’ by Bella and accordingly printed in italics, we are still inside McCandless version of events – is it he who really holds the pen?

14

Glasgow to Odessa

Chapter 14 begins with a poem in rhyming couplets. Bella proves to be as gifted a poet as McCandless. Thankfully her Shakespearian homage ends before the chapter is out. In the poem and subsequent prose Bella details her voyage by sea, discusses the various nationalities with whom she comes into contact, and gleefully recounts her treatment of the ailing Wedderburn which ranges from intense passion, tender care and complete abandonment. To cap it all Wedderburn gambles his money down the drain and is left financially and emotionally dependent on Bella (who refuses to make him an honest man). As if that were possible…

15

Odessa to Alexandria: The Missionaries

Bella meets Dr. Hooker and Mr. Astley on board a cruise liner. The American evangelical eugenicist and English Malthusian provide Gray with ample opportunity to discuss oppositional word views (and of course to promote his own: socialism). For more of this, you’ll want to check out Alasdair Gray-Social-Conscience. The chapter ends with a heart-wrenching, handwritten, tear stained scrawl from Bella: ‘whi did yoo not teech mee politics God?’ (p145). (See Duncan Wedderburn for the backstory to the creation of this letter by Gray with help from his wife Morag). After reading the letter, the reader might guess that Bella was emotionally unsettled by the unsavoury ideologies of Hooker and Astely. It is not until chapter 17, however that we discover the true cause of her distress.

16

Alexandria to Gibralter: Astely's Bitter Wisdom

Chapter 16 offers Gray the opportunity to lecture his reader (in a highly ironic tone) in the voice of Harry Astely on a range of Gray adjacent subjects including Education, History, War, Unemployment, Freedom, Free Trade, Empire and Self Government (pp. 155-63). After hearing Astley’s ‘bitter wisdom’ Bella’s logical conclusion is: ‘I must be a socialist’ (p164). We shouldn’t forget that before Godwin, Bella’s maker is Gray. For more on editorial bias you’ll need to take a wander with Gray-the-Editor.

17

Gibralter to Paris: Wedderburn's Last Flight

Chapter 17 begins with Bella narrating her and Wedderburn’s decision to leave the cruise liner together at Marseilles and from there, travel to Paris. There the couple bunk down in the Hotel de Notre-Dame run by Cockney Madame, Millie Cronquebil. And yes, I do mean Madame in the suggestive sense of the word. The hotel is a brothel. Madame Cronquebil is its manager – a key fact that Bella discovers during her stay in the French capital. The narrative then takes a non-linear dive back to Alexandria to recount the event that sparked Bella’s sorrowful letter. But I’m not going to give that away now! You’ll have to head to Alasdair Gray-Social-Conscience to find out more. By the end of the chapter, Wedderburn is utterly deranged and is finally liberated by Bella who sends him home with the last of her money.

18

Paris to Glasgow: The Return

Bella learns the ins and outs of working life at the brothel and commits to coming home to Glasgow as a well-rounded woman and the best of partners to McCandless, her husband-to-be.

A good summary of several important chapters. Well done. You might want to think about comparing the Bella’s journey to that of Wedderburn’s a little more clearly. In Paris to Glasgow we get a beautiful travelogue of Bella and Wedderburn’s elopement. From the glamorous casinos to houses of ill repute on the left bank, we see Bella grow from someone who can barely write: ‘I am glad I bit mister Astley’ (p150), to a strong, smart, funny woman. Her scrawl is both a laugh out loud moment, and later - when we discover the reason for her attack - a moment underpinned with despair. Getting to see Wedderburn go the other way from Bella, from suave gambler to pathetic mummy’s boy, is just as much fun as watching Bella excel. The people Gray’s heroine meets on the way are beautifully drawn (sometimes literally). They create a journey of discovery and excitement as much for us as they do for her. Astley’s Bitter Wisdom is a hilarious section about his views on putting the world to rights. And demonstrates why he deserves to have been bitten.

19

My Shortest Chapter

Chapter 18 ends with Bella returning to 18 Park Circus. Is the corresponding door and chapter number number a coincidence?? Probably. But read into it as you like. Chapter 19 takes up the question Bella asks in the final lines of the previous chapter:

‘‘Where is my child God?’, she asked’

(p191).

Godwin has no answer ready. He blusters. He bluffs. The truth is buried. Satisfied, Bella wraps her arms around Godwin. McCandless wraps his arms around Bella. And Gray’s shortest chapter ends:

The three of us lay a long time like that

(p193).

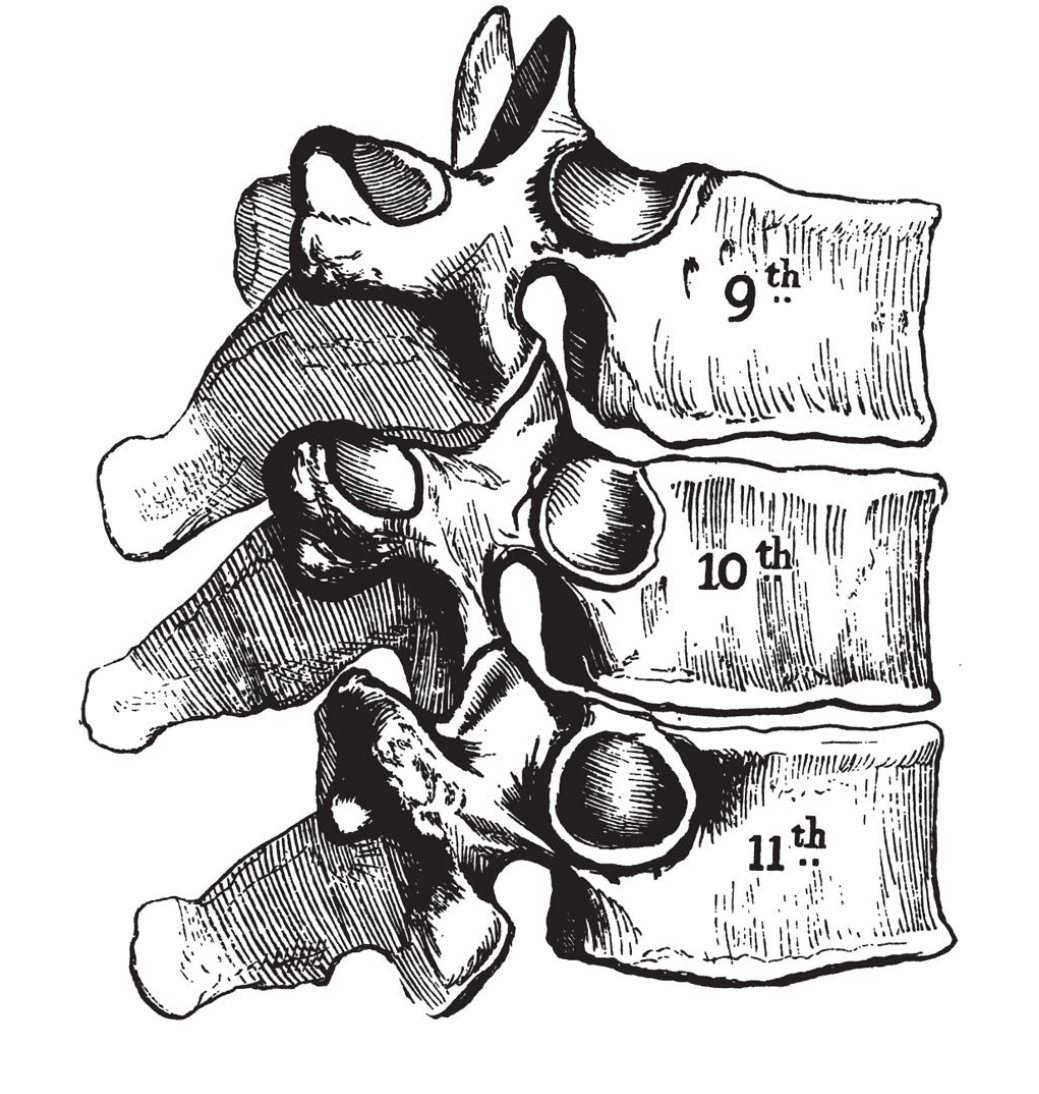

Ilustration from Grey's Anatomy (1858) printed in Poor Things (1992) , courtesy AGA

The three vertebrae evoke the trio's embrace and recall the image on the novel’s cover. But perhaps your sense about what that image represents has now changed. What once communicated familial tranquillity, is now laced with duplicity, jealousy and - for Bella at least - enforced naivety. Bella never learns the full extent of her history. She knows - as Godwin tells her - that she has lost her child. She does not know that her ‘dead’ child is alive inside the body she later discovers belonged to Victoria Blessington (nee Hattersely). Joyful, idiosyncratic, unstoppable, Bella Baxter’s comprehension of her own truth is stopped short by Godwin’s lies. Would she become the ‘cynical parasite’ (p196) she so despises if she knew her guardian’s secret? For a closer examination of this question, see Bella Baxter or to learn more about the relationship between text and image in Gray’s novel click on Illustrations. For more symbolic imagery visit Bella Caledonia.

Keep up the good work! You perhaps expand your point by referring to the paratexts that supplement the main body of Gray’s novel. Not only do we get some exquisite writing (from fake Kipling poems in the Notes to cod Shakespearean couplets and deep research of faux gothic Victoriana), we also get plenty of original Gray artwork. Bella Caledonia (p45) has become an iconic image for the Scottish Independence movement. The portraits and illustrations throughout the novel are not there simply to make things look pretty, however. Through his art, Gray’s words begin to break down and take on new meaning.

20

God Answers

Does God(win) really answer Bella’s question? No. He doesn’t. She answers it for him with a substantial monologue:

‘Were you afraid your answer would drive me mad? […] I was a child when I ran away from you - how could you have told childish Bella Baxter that she had lost a child of her own? […] You made me strong and sure of myself, God, by teaching me about the fine and mighty things in the world and showing me I was one of them. You were too sane to teach a child about craziness and cruelty’ (p195).

We might stop and think about the novel's editor here. As we know, in his role as Gray-the-Editor, the fictional Alasdair Gray has rewritten McCandless’ chapter headings. Is our trusty editor priming us to take Godwin’s evasions as an answer to Bella’s question about the ‘death’ of her child? Hmmm...

Really good. You seem to be getting into your stride. Truth is a central theme (and a slippery concept) in Gray’s Poor Things - inwhat other ways does it unfold in the novel? There are only a handful of events in the novel that are inarguable. Even when the characters give their own truth they are undermined not long after. There is doubt, confusion and contradiction, yet there remains something deeply earnest at the heart of the novel. You don’t feel like you’re being lied to or hoodwinked despite being constantly lied to and hoodwinked. An impressive feat. I want to say something about the truth of storytelling being the only thing we can rely on, but I’m sure there will be something in the novel that compromises this!

You might want to think of some more examples. Here’s some starting points for you in the meantime:

Table of Contents: this comes towards the end pf the introduction and doesn’t include any reference to Victoria McCandless’ letter, Gray-the-Editor’s Notes or the illustrations. The narrator may say that the table of contents is purely to back up Archie McCandless’ found work with historical accuracy, but this deliberate obfuscation adds to the constant blurring of the truth. The first page after the verso title page also highlights an error with one of the etchings in an erratum slip. We know from the very start that we might need to find our own truth.

Archie’s story: Archie seems so pitiful and pathetic that I’m not sure we even contemplate not believing him. He has come from humble beginnings to be a solidly middle class medical man. Of course we would believe his story. Even the Frankenstein stuff. He feels honest and genuine in his actions towards Godwin and Bella, almost painfully so, and while we can laugh at his sincerity and silliness we still retain a degree of sympathy for him.

Victoria’s story: However! Victoria’s letter presents her husband as a hyperbolic crank. She completely rubbishes all of his claims to the supernatural. We wonder why we would ever have trusted Archie in the first place. Victoria is completely heroic. She survived a torrid first marriage and remade her life in the service of others. Her clinics and training methods in Glasgow were revolutionary. Her defence of these in court and her socialist views make her the voice of reason.

Gray-the-Editor’s story: However! Gray’s notes go on to portray Victoria as an untrustworthy crank. Sort of. He discredits her in a few significant ways and while there are many ways in which we can admire her we are also never entirely sure who she is. But why should we trust him? He doesn’t even claim to be the author! We are definitely offered some truths at the end of the novel. It’s just tricky highlighting what they are.

21

An Interruption

McCandless and Bella set off to be married. They arrive at the church with Godwin and housekeeper Mrs. Dinwiddie in tow. Five mysterious witnesses appear at the wedding. ‘This marriage cannot take place!’ one cries (p202). It's General Blessington, husband of Victoria Blessington (nee Hattersley) (now transformed into Bella, if you believe McCandless’ account of events in Episodes). Anyone getting Jane Eyre vibes? You should be. Poor Things is packed full of intertextual references like the wedding scene in Charlotte Brontë’s story of love and betrayal. For a (largely!) comprehensive guide to Gray’s intertextual references, make your way to Intertexts in the Character Gallery.

Good. The wedding scene is a key incident in the novel: Archie turns up expecting to have the greatest day of his life - his crowning glory. It will just be the menage plus Mrs Dinwiddie there to celebrate the vows. The snow is falling on Christmas morning. Scrooge could be bellowing out the window for a young scamp to buy the biggest turkey possible. Who are these unexpected aristocrats come to spoil the day? It is literally a ‘speak now or forever hold your peace’ moment. What Victorian melodrama! Don’t forget either that Gray blends his Gothic allusions with Scottish traditions. For example, in Notes, he/Gray-the-Editor explains the history behind the good old Scottish scramble that we see in chapter 21, and commenting that after the bride throws coins to the waiting crowd ‘the weakest and smallest be left weeping with trampled fingers’ (p289). This would undoubtedly have been Godwin and Archie. These odd little misfits were always going to find each other. Their detached, emotionless early exchanges in chapters 1-7 are a comic joy.

22

The Truth: My Longest Chapter

Buckle up. It’s McCandless’ longest chapter. Or at least so Gray claims. I haven’t counted the pages.

The wedding guests are huddled together in the study of 18 Park Circus. And aren’t they a strange bunch. We’ve got our ménage a trois alongside General Blessington and his four ‘parasites’: Dr Prickett, Detective Inspector Grimes, his solicitor, Harker and Blaydon Hattersely. The latter is the father of Victoria Blessington (who is the disputed wife of General Blessington). A debate ensues (in a variety of flamboyant accents). Is Bella actually Victoria Blessington? Is she a raving lunatic? Are her carnal desires an abomination? Has she been resurrected by Godwin Baxter? Do Glasgow doctors frequently perform similar acts?! Should she go back to Blessington or stay with Godwin? There's a lot of toing and froing in this chapter, and though Bella discovers that her parents did not die in an Argetine car crash, many of questions go unanswered. We do, however, get a sense of the maltreatment inflicted upon Victoria/Bella - whoever she is - at the hands of her former male guardians. Out of this cacophony, at least one thing is confirmed, Bella chooses to stay with Godwin ‘in a home that is not a prison’ (p232).

Excellent commentary. Given all the toing and froing and backwards and forwards and claims and counterclaims, there isn’t really a real turning point in Gray’s novel. Things are always changing and turning, but the marriage scene and its aftermath might be considered a ‘key incident’, if not a turning point. Think about the relationship dynamics in these scenes compared to the bulk of the novel: Godwin gets everyone back to Park Circus to make sure a right good cover up and scandal avoidance plan is in place. There is a whole cast of characters debating who Bella actually is. The bulk novel puts her at the forefront – whichever version of her you prefer – and her story and vision and utter force of personality really carry it. But at this point, she is very much voiceless. Uncomfortable.

23

Blessington's Last Stand

Hang on. You didn’t think chapter 22 was our neat happy ending tied up in a bow? Not in this novel. Chapter 23 sees Blessington hold the room at gunpoint. The result? Bella intervenes, gets shot in the foot, refuses to shoot Blessington ON HIS COMMAND. She is, however, more than happy to reveal the General’s alias ‘Monsieur Spankybot’, a regular patron at the Hotel de Notre-Dame. Finally, Blessington and the parasites leave. Two days later the British press report Blessington dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head (p239).

Good. Do you think Bella’s status changes by the end of the chapter or not? After all, she does what her hapless, helpless, hopeless pals can’t, and resorts to action. She suffers an injury (Godwin and Archie jump to her rescue once everything has calmed down and look like heroes. Typical). But it’s Bella who saves the day, sets them up for life and gives us the very satisfying image of the General traipsing out of the house defeated and sad with only his stiff upper lip and sense of fair play remaining. But there is no mention of any of this from Victoria’s letter - so it maybe didn’t happen!

24

Goodbye

McCandless’ final chapter begins ‘Reader, she married me and I have nothing more to tell’ (p240). Well that’s not exactly true. The rest of the chapter is taken up by recounting the death of Godwin Baxter – an event which casts more light on the stilted relationship between the two men. ‘I sat down and wept uncontrollably [at the news of Godwin’s death’ McCandless states. ‘Thank you again, McCandless, those tears console me. They mean I have been good for you’ (p242). Ironically, in the next paragraph we find out that McCandless has not been so good for Godwin – the younger doctor’s engagement to Bella set off a sequence of events which fatally damaged the latter’s health. A gruesomely Gothic deathbed scene takes place. McCandless ends his account by stating: [I] will prove the factual ground of all I have written here’ (p244).

Excellent commentary on the theme of truth. On Baxter’s death: you do have to choose an account when it comes to his final moments. In Archie’s it’s just him (Godwin can’t bear Bella being there – he’d stay alive for her). In Victoria’s (or Bella’s) account, both McCandless and Victoria/Bella are there but she is the one to take up the burden and administer the potion that kills him in a deeply loving but heart-breaking manner. And where is the Baxter mausoleum? You can pay your respects to the entire Baxter and McCandless clans in the Necropolis in Glasgow according to Gray-the-Editor. There’s even a handy picture to guide you. And since it’s Gray telling us this in his editor’s notes, it must be true…

Letter to Posterity

A letter from

Victoria McCandless M.D

to her eldest surviving descendent

in 1974

correcting what she claims are errors

in

EPISODES FROM

the EARLY LIFE

of a

SCOTTISH PUBLIC HEALTH OFFICER

by

her late husband

Archibald McCandless M.D.

b. 1857 – d.1911

Like Micheal Donnelly, Victoria also thinks McCandless’ version of events is a load of old rubbish. It’s here in the narrative we discover that the crafty editor kept this likely story a secret until we (poor fools) had read the version of events that he believes to be true. Editorial bias rises to the surface of Gray’s cleverly plotted text once more. Was everything we believed a lie??

Excellent comparison between narrative structure and content here. You could expand with a couple of key points that we could group under the heading ‘narration and playfulness’. In her Letter to Posterity Victoria McCandless gives her account. She tells us she only ever loved Godwin (he does seem to be a bit of a visionary), she thinks her husband Archie is a crank (of course he is!) and then trashes his account as a complete load of rubbish. Of course, it is! We feel a bit daft about being drawn into all this Frankenstein nonsense and feel happy to be in the presence of someone eminently sensible. And what about Gray’s source novel Frankenstein? Mary Shelley’s novel is epistolary in form, and while there are some quibbles over certain details, there are also scores of established facts. There are elements of this form in Poor Things and, while there is a broad chronological track that is followed, the way this story is formed, created and told, is to delight and pose questions. And it’s a lot of fun. Now, I said that Victoria is eminently sensible, but Gray makes her state in full sincerity that Robert Burns wrote the Jacobite song Loch Lomond. Here we have to turn to Notes Critical and Historical. These pompous, pedantic yet often fascinating clarifications look well-intentioned and are designed to enshrine authorial control. But they are anything but. While also enjoyably enhancing the case for Glasgow as a city of the arts, the notes add no certainty, and contribute to the sense of mystery. It’s in Notes Critical and Historical that Gray, in his role as the novel’s ‘editor’ corrects Victoria’s attribution of Burns as the writer behind the Bonnie Banks of Loch Lomond. So, it looks like Victoria’s account is also full of inaccuracies. How many more did we miss? Who do we trust? And talking of trust. let’s not forget Micheal Donnelly. Poor Michael! The archivist found McCandless’ manuscript in an empty box and gave it over to his dear friend Alasdair to have a look at. There then was the argument with Gray commenting: ’if my readers trust me I do not care what an “expert” thinks’ and, concerning the lost manuscript which only exists in photocopied form: ‘mistakes are continually happening in book production, and nobody regrets them more than I do’ (pXVI). What a way to start telling a story. It makes unreliable narrators look decidedly trustworthy.

Notes Critical and Historical

by Alasdair Gray

‘Notes Critical and Historical’ – well these are bound to be true, aren’t they? Wrong. Like the Index of Plagiarisms in Gray’s debut novel, the ground-breaking Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981), Poor Things’ Notes Critical and Historical are a mix of fact, fiction and somewhere in between. A lengthy section of this appendix is given over to detailing the life of Victoria McCandless M.D. We learn that after a successful career as a pioneering doctor, socialist and suffragette – with friends in poets Hugh MacDiarmid and Hamish Henderson; painters Robert Colquhoun and Stanley Spencer; Red Clydeside leaders Kier Hardie and John Maclean; writers H.G Welles and George Bernard Shaw –Victoria McCandless ends up denigrated by the press and ridiculed by society. Gray leaves us with a final image of Victoria, ‘The Dog Lady’, operating from a small surgery, mainly for sick animals, from her home in 18 Park Circus (p313). So, if Poor Things really is a fiction why would Gray so violently diminish the immense achievements of his feminist heroine? Some of those questions can be answered by clicking on Victoria McCandless image in the Character Gallery. But first it's only right you meet the supposed author of Gray's book...Dr. Archibald McCandless writer of Episodes from the Life of a Scottish Public Health Officer (1909).